Thursday, May 2, 2013

A Quiet Place in the Country

Although I have never thought of Nordic Italian Stallion Franco “Django” Nero as a seemingly schizophrenic and angst-ridden art fag who creates vulgar abstract paintings of the childlike finger-paint sort, he once played one in the unsurprisingly underrated, avant-garde proto-giallo Italian-French horror production A Quiet Place in the Country (1968) aka Un tranquillo posto di campagna aka Un coin tranquille à la champagne directed by Guido commie auteur Elio Petri (The 10th Victim, Property Is No Longer a Theft)—a filmmaker whose mind was apparently as plagued by anguish and existential crisis as the characters he cinematically portrayed. Winner of the Silver Bear award at the 19th Berlin International Film Festival, A Quiet Place in the Country is now all but allocated to the celluloid dustbin of history, which is generally a positive thing when it comes to far-left commie, psychoanalytic/psychedelic mumbo jumbo from the late-1960s, yet Petri’s film, not unlike similarly underrated works like Death Laid an Egg (1968) aka La morte ha fatto l'uovo directed by Giulio Questi, has enough aesthetic integrity and intriguing thematic complexity to warrant reconsideration today as an avant-garde psychosexual horror-thriller that poses enough questions about the crisis of the Western soul to be more than relevant for today’s viewers, even if the majority of spectators will have too much trouble digesting such a decidedly discombobulating and deranging cinematic work that poses many important questions but has no real answers, thus not falling prey to the phoney sort of hope that is oftentimes espoused by lying leftist idealists. A potent albeit peculiar piece of quasi-supernatural surrealism about a psychologically and psychosexually perturbed painter who finds nil solace in his artistic success nor lavish lifestyle, so he moves out of the soulless city into the nice and peaceful country in a desperate attempt to cure his all-consuming weltschmerz, A Quiet Place in the Country is indubitably a work that has much in common with such masterpieces as Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960), Ingmar Bergman’s Hour of the Wolf (1968), and Paul Verhoeven’s The Fourth Man (1983) in its unsettling and perversely penetrating portrayal of a mentally unhinged artist on the brink of mental dissolution. Of course, the major difference between all these other films in terms of storyline is that the protagonist of A Quiet Place in the Country is obsessed with the beauteous ghost of a slutty 17-year-old countess who met a rather grizzly fate during the Second World War that may or may not exist. Told from the perspective of an exceedingly unreliable painter at war with his own mind and art, A Quiet Place in the Country is assuredly one of the greatest and most complicated cinematic stories of a haunted artist.

Leonardo Ferri (Franco Nero) has a lot of problems but virtually all of them are the product of his haunted and afflicted mind that cannot conform to the ways of technocratic modernism, as he is a rather successful degenerate painter whose art resembles what might happen if a rainbow were to barf on a piece of canvas. During the first couple minutes of A Quiet Place in the Country, Leonardo, in a surrealist pop-art scenario that is later revealed to be a dream, sits somberly and half-naked in a chair that he is tied to in a striking scene of cinematic sadomasochism. His wife/manager Flavia (Nero’s real-life, two-time wife Vanessa Redgrave) greets him when she gets home with all the worthless gadgets and knickknacks she picked up at the store, including a waterproof TV, a transistor fridge, an erotic electric magnet and other seemingly pointless and worthless gimmick items made to appeal to the Faustian need to conquer nature, which now has reached a ridiculous and patently pointless level where instead of dominating continents and peoples as was done in the past, Western man can only try in vain to dominate his own domestic laziness and unquenchable thirst for material possessions, which only further feeds his feeling of worthless. During the same dream, Leonardo also dreams that his now-naked wife is murdering in a bathtub via a number of Norman Bates-esque butcher knife stabs to the chest. While he finds his wife’s incessant nagging about his need to be at art shows to display and promote his work to be rather annoying, Leonardo is all the more disturbed and plagued by popular symptoms of the modern world, including charity/altruism (a supposed representative from the “Artist for Orphans Associations” tries to swindle him), consumerism (all the items that make his already pointlessly complicated life all the more unbearable), pornography (he becomes more interested in porn magazines than his real flesh and blood wife), poverty porn (an obsession with looking at everything grotesque the Third World has to offer), and guerilla warfare (with seems to inspire the painter’s need to rebel against his bourgeoisie background and the director's seeming leftist xenophilia). When it comes down to it, Leonardo—who is certainly no da Vinci—hates reality as explained in delusional quasi-commie statements like, “canvases and paints should be free for everybody. One hour a day,” but, of course, Leonardo’s dream of an intangible Marxist Utopia is the least of his problems as his innate disdain for reality begins to take a homicidal form inspired by his fanatical fetishism for a voluptuous femme fatale phantasm of the supernatural S&M variety.

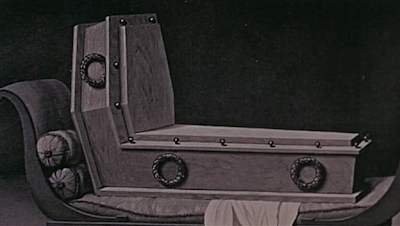

One day while driving around in a rather scenic rural area, Leonardo is greeted by his doppelgänger at the gate of a classy country home, a seemingly ancient Venetian villa, which he immediately jumps out of his car to investigate, but not without bringing his trusty “Playgirl” and “Super Sex” magazines like any reasonable porn addict would. To Leonardo’s credit, his wife ruins any moment of sexual passion for him as she always answers the phone anytime they are about to sexually embrace because, after all, it “might be important” and she would not want to jeopardize her financial security for a potential business deal. Of course, Leonardo eventually explores the giant yet somewhat dilapidated villa that caught his fancy and runs into its particularly peculiar caretaker, a swarthy and slightly overweight 50-something-year-old named Attilio Bressan (Georges Géret). When Leonardo says he is “looking for a quiet place in the country,” Attilio responds “only death is quieter than this,” which ultimately turns out to be quite the understatement. Unable to churn out a mere painting during a three month period, Leonardo is finally able to convince his wife Flavia, who probably believes it will be good in the long run for her bank account, to buy the Venetian villa where the painter immediately gets to work as hired workers, including a ravishing young housekeeper named Egle (Rita Calderoni), begin restoring his homestead. During Leonardo’s first night in the home, some unknown entity destroys all of the artist's paintings and art supplies, of which he initially accuses Egle and her little brother who she seems to have an incestuous relationship with as they are shown embracing in bed, but something sensual and supernatural seems to be responsible for the disturbances. The next day, Leonardo learns about the mysterious “little countess” named Wanda (Gabriella Grimaldi), a royal nymphomaniac described as being “really a beautiful creature and a slut” by local townspeople who was randomly shot to death in 1944 by a British fighter pilot. Soon thereafter, Leonardo can no longer focus on his art and becomes involved in metaphysical necrophilia of sorts, spending all his time questioning local country folk about Wanda and her effect on the town and even visiting her elderly and senile mother, who tries to get in the painter's pants. Leonardo eventually learns that every man in town shared carnal knowledge with Wanda, including Attilio, who killed a German corporal after walking in on her in the act with the unlucky Teuton. Attilio, who is a serious alcoholic that always carries a glass of the good stuff with him wherever he goes, blames himself for Wanda’s death because she helped him bury the dead kraut in a field, at which point in time she was shot down by the British fighter pilot in a scenario of absurdly tragic poetic justice. Apparently, wanton Wanda felt no sense of sympathy for the kraut that she inadvertently caused to be murdered due to her intemperate lecherousness. One dark and ominous night, Leonardo holds a séance with Attilio and his wife, but also every pompous person he knows in the art world, which results in Flavia’s seemingly supernatural strangulation and inspires the painter to finish what she started. In the end, Leonardo gets the peace and quiet he was always searching for, albeit against his own will in a mental institution where his pathological porn addiction takes on preposterous extremes, but considering the painter's psychotic persuasion, one can never be sure if anything that goes on is a depiction of reality or his own macabre mental derangement.

Decades after completing A Quiet Place in the Country, director Elio Petrio would state of the film, “The reason why I defend A Quiet Place in the Country is because it is the portrait of an artist, of a middle-class intellectual and of his division. He was a middle–class artist who, as far as his expressive means were concerned, tried to upset forms and formulas and who found himself prisoner of a serial production system. Thence his escape towards the ghosts of romantic culture.” Indeed, although directed by a quasi-Marxist auteur who stuck it to the middle-class and the innately materialistic and mundane lives they lead, A Quiet Place in the Country transcends Frankfurt school psychobabble and is no piece of needless novelty intellectualism of the Trotskyite sort, but a serious, albeit aesthetically and thematically schizophrenic look at the crisis of the Western soul in a manner that works more effectively in the medium of abstract cinema form than in writing. Petrio even went so far as to admit regarding A Quiet Place in the Country, “The film was a criticism of the intellectual, indeed from the inside. In short, we were on the threshold of ’68 and this is my last film before Investigation; that is before making films I could feel were useful to some cause,” so it is rather unfortunate that he did not realize that the political persuasion he subscribed to as a quasi-communist was just as deluded and materialistic, and thus unsatisfying to the soul as the bourgeois modernism he negatively portrays in the film. As protagonist Leonardo states in the film, “I’m forced to follow the rules of the market. I have to abide by them. I can’t change them,” thereupon admitting to a passive feeling of unshakable impotency in the face of a shallow modernism and as C.G. Jung once wrote regarding human nature in his work Psychology and Alchemy (1952), “People will do anything, no matter how absurd, in order to avoid facing their own souls. They will practice Indian yoga and all its exercises, observe a strict regimen of diet, learn the literature of the whole world - all because they cannot get on with themselves and have not the slightest faith that anything useful could ever come out of their own souls. Thus the soul has gradually been turned into a Nazareth from which nothing good can come,” and such is the fate that ultimately leads to Leonardo, who has a delusional obsession with an intangible entity—a banshee nympho bitch of the decadent aristocrat sort—from suffering a complete mental break in the tradition of Friedrich Nietzsche; a man that was never able to overcome the nihilism that inevitably took over his body and soul.

Featuring what is probably the most decidedly discordant and intentionally atrocious score Italian maestro composer Ennio Morricone ever created, A Quiet Place in the Country is a potent piece of conscious aesthetic decadence with a soul, if not a rather “haunted” one in the fullest sense of the word. A rare and uncompromisingly idiosyncratic piece of psychological and psychosexual horror that combines sardonic black humor, supernatural surrealism, a curious combination of pop-art, art deco, and Gothic imagery, and a darkly romantic grotesque aestheticism, A Quiet Place in the Country is certainly a work of its time that will probably just plain agitate most modern viewers due to its erratic editing and music, and ambiguous brand of storytelling, but for those that understand and appreciate the film, it surely makes for one of the most absurdly underrated horror films—be it Italian or otherwise—ever made. Like a psychedelic surrealist take on Rainer Werner Fassbinder's Martha (1974), albeit with the protagonist and director as the masochist and woman as sadist as opposed to the opposite scenario as featured the German New Cinema auteur's Sirkian melodrama, A Quiet Place in the Country lets the viewer know there is no escape from modernity, even in a place where gangsters, pimps, prostitutes, and Marxists are scarce, but the film does confirm that rural areas make for more scenic and spiritual living, though it might drive one to spiritual necrophilia with a romantic past that is long deceased, which still beats parallel parking and living amongst the assorted 'mystery meat' that populate corrupt cosmopolitan cities.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 02, 2013

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.

No comments:

Post a Comment