I have been following the work of so called "Occult Fascist" Boyd Rice for many years now yet I wouldn't call myself a true fan. Quite honestly, Rice's antics annoy me more than anything. When I first discovered his work years ago, I felt as if I had finally found a modern artist with testicular fortitude, but I soon realized that I was sorely mistaken. Although Rice is a man who has no problem butchering sacred cows nor violently stirring politically incorrect controversy, his lack of genuine idealism and inconsistent belief system(s) just goes to show that he is first and foremost a conman who reinvents himself anytime his routine begins to be boring and no longer alluring. During his unconventional career, Rice has played the role of a Satanist, pseudo-fascist, Mansonite, satirical social Darwinist, artsy fartsy noise musician, promoter of Tiki Bar Kultur, and many more other controversial roles, yet he has neglected to stay truly committed to anything aside from his Carney and contrarian nature. Had Mr. Rice lived in a time when fascism was vogue, he would have most promoted the Marxist or anarchist line, but, instead, he grew up in an era where racial elitism (of the Aryan persuasion) is purely taboo, hence his ambiguous attraction and flirtation with it. Of course, anyone that knows anything about Boyd Rice is aware that the self-proclaimed iconoclast developed many of his greatest friendships over the years with Jews and people of Jewish descent, thus those that think he is an antisemite of sorts know next to nil about the subversive showboat showman. Despite his lifelong aversion to Christianity, Boyd Rice has also spent sometime attempting to prove he is a descendent of Jesus Christ himself. In the 4 hour long "tour de force" documentary Iconoclast directed by Larry Wessel (I will leave it up to the reader to figure out this filmmaker's racial character), Rice's life story is unraveled in a sentimental manner worthy of a Joseph Goebbels' style propaganda flick on a modest budget. Despite his self-proclaimed elitist philosophy, Rice is a proud high school dropout who stated of his rather successful but marginally notable artistic career that it, "is a testament to the idea that you can achieve whatever the hell you want if you posess a modicum of creativity, and a certain amount of naivete concerning what is and isn't possible in this world. I've had one man shows of my paintings in New York, but I'm not a painter. I've authored several books, but I'm not a writer. I've made a living as a recording artist for the last 30 years, but I can't read a note of music or play an instrument. I've somehow managed to make a career out of doing a great number of things I'm in no way qualified to do."

Monday, May 30, 2011

Iconoclast

I have been following the work of so called "Occult Fascist" Boyd Rice for many years now yet I wouldn't call myself a true fan. Quite honestly, Rice's antics annoy me more than anything. When I first discovered his work years ago, I felt as if I had finally found a modern artist with testicular fortitude, but I soon realized that I was sorely mistaken. Although Rice is a man who has no problem butchering sacred cows nor violently stirring politically incorrect controversy, his lack of genuine idealism and inconsistent belief system(s) just goes to show that he is first and foremost a conman who reinvents himself anytime his routine begins to be boring and no longer alluring. During his unconventional career, Rice has played the role of a Satanist, pseudo-fascist, Mansonite, satirical social Darwinist, artsy fartsy noise musician, promoter of Tiki Bar Kultur, and many more other controversial roles, yet he has neglected to stay truly committed to anything aside from his Carney and contrarian nature. Had Mr. Rice lived in a time when fascism was vogue, he would have most promoted the Marxist or anarchist line, but, instead, he grew up in an era where racial elitism (of the Aryan persuasion) is purely taboo, hence his ambiguous attraction and flirtation with it. Of course, anyone that knows anything about Boyd Rice is aware that the self-proclaimed iconoclast developed many of his greatest friendships over the years with Jews and people of Jewish descent, thus those that think he is an antisemite of sorts know next to nil about the subversive showboat showman. Despite his lifelong aversion to Christianity, Boyd Rice has also spent sometime attempting to prove he is a descendent of Jesus Christ himself. In the 4 hour long "tour de force" documentary Iconoclast directed by Larry Wessel (I will leave it up to the reader to figure out this filmmaker's racial character), Rice's life story is unraveled in a sentimental manner worthy of a Joseph Goebbels' style propaganda flick on a modest budget. Despite his self-proclaimed elitist philosophy, Rice is a proud high school dropout who stated of his rather successful but marginally notable artistic career that it, "is a testament to the idea that you can achieve whatever the hell you want if you posess a modicum of creativity, and a certain amount of naivete concerning what is and isn't possible in this world. I've had one man shows of my paintings in New York, but I'm not a painter. I've authored several books, but I'm not a writer. I've made a living as a recording artist for the last 30 years, but I can't read a note of music or play an instrument. I've somehow managed to make a career out of doing a great number of things I'm in no way qualified to do."

After watching Iconoclast, I have to admit that the documentary neither fell short nor exceeded my relatively apathetic expectations. After all, I see Boyd Rice's body of work as nothing more than a dubious but sometimes entertaining collection of novelties. By his own admittance, Rice has shown pride in his lack of skill in each artistic medium he has dabbled in, like a dilettante who is oddly more interested in monetary success than the artistic outcome of his experiments. In my opinion, the individuals that Boyd Rice has had the honor of collaborating with over the years have always tended to be much more talented and equally more dedicated than he is. For example, Boyd Rice has collaborated with Douglas P. of alpha-Neofolk group Death in June on a number of occasions. In my opinion, all of the Death in June albums Rice worked on are infinitely more interesting and enjoyable than anything NON (Rice's main musical project) has ever produced. Michael Moynihan - the humble protégé of Boyd Rice - has also completely outdone his former teacher. Although Rice has bitterly stated some not so nice things about Moynihan's Neofolk/Post-industrial musical group Blood Axis in the book Art That Kills: A Panoramic Portrait of Aesthetic Terrorism 1984-2001; the project certainly puts the non-musical nature of NON to shame. Moynihan has also shown that he is a far more literate and serious writer than Rice; producing translations of works by aristocratic Sicilian philosopher Julius Evola, an excellent occidental pagan kultur journal (Tyr: Myth—Culture—Tradition), and various other notable works (Lords of Chaos). Although Boyd Rice wrote some interesting pieces for RE/Search Publications on forgotten/bizarre films and pranks during his early career, his writing skills have never really advanced since then. A couple years ago, Rice released his noticeably thin book "NO"; a collection of essays and personal insights. Although NO is a clever book that is certainly worth checking out, the work can be quite annoying in parts, especially when Rice (who is now a middle-aged man) belittles his own father in a totally petty and immature manner. In my opinion, NO is quite symbolic of Boyd Rice in general, as it is a work that shows evidence of a witty fellow who seems to be somewhat lazy due to his obsessive misanthropy, hence his less than serious body of work. Accordingly, in the documentary Iconoclast, Boyd Rice makes it perfectly clear that he is a lifelong jokester and prankster with an incapacity to take anything too seriously, thus it should go without saying that one shouldn't take the iconoclast himself too seriously.

During his lifetime, Boyd Rice has had friendships with some of the most hated men in the United Sates of America. Rice was friends with Church of Satan founder and High Priest Anton Szandor LaVey until the good Doktor's death in 1997. During Iconoclast, Rice joyfully recollects his personal experiences with LaVey. Rice also discusses his quasi-friendship with Charles Manson; a brief relationship that eventually turned bitter. The only segment of Iconoclast that offers any criticism of Boyd Rice is from Manson who describes his former friend as a poser rock star that likes to play dress up in military uniforms but is incapable of following orders nor respecting others. I have to admit that Manson's criticism of Rice was quite hilarious and undeniably true. For whatever reason, Rice neglects to mention his only son Wolf; a boy that apparently suffers from some type of debilitating physical disorder (so much for Rice's topnotch Christ-like genetics). Instead, it seems that Rice's only real family are his carefully selected friends and followers. I must admit that I was quite happy to see footage of Rozz Williams (lead vocalist of Christian Death and Shadow Project) featured in Iconoclast that was taken right before his suicide on April Fool's day. According to Boyd, Rozz Williams used to pathologically stalk Rice around Los Angeles. Unsurprisingly, Rice also inspired Marilyn Manson and his pseudo-fascistic Carney cabaret routines. Out of all the friendships Rice has developed over the years, his cordial relationship with Christian Televangelist Bob Larson (which spans over two decades) seems to be the strangest. Of course, Rice and Larson are not total opposites as they are both talented showman who have an knack for spellbinding lesser beings. Anyways, if you expect Iconoclast to be in anyway an objective portrayal of Boyd Rice and his unconventional life, you're probably looking for a film that will never be made. At the most fundamental level, Iconoclast is a celebration of Boyd Rice's life with the subject as the somewhat unreliable narrator. Boyd Rice is a man that most people either love or love to hate, although I find myself fitting into neither of those groups. That being said, Iconoclast is the kind of film that the viewer will either love or hate, but it is doubtful that anyone will find it to be forgettable.

As mentioned in Iconoclast, Boyd Rice once created a painting of a primitive looking skull using the vaginal blood of a thirteen year old virgin girl. During the last hour of Iconoclast, Rice proudly admits that he learned from such mentors as Anton LaVey and Charles Manson that one must "break-in" a girl (like a pimp) before another man gets the chance to do so. Call me a puritanical prude, but I found Rice's interest in virtual preteens to be, to say the least, quite deplorable. Of course, that is just one of the many things that I found to be repellent regarding Boyd Rice's life and philosophy. Personally, when I hear the word "iconoclast", I think of people like German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche and German-American sage journalist H.L. Mencken, as both men left a penetrating, highly influential, and an ultimately erudite body of work. I would certainly never put someone like Boyd Rice in the same league as a Nietzsche nor a Mencken, but, instead, in a category with nihilistic punk rock frontmen like Darby Crash of The Germs or subversive filmmakers like Bruce LaBruce. Of course, we live in an era where the general public is increasingly less literate and gravitates towards the primitive and highly sensual, thus keen literacy and complex creations are not as important in the present day. As Rice has freely stated in a totally braggart manner, he is quite proud of his limited artistic skills and less than minimalistic creations. After all, most American's easily fall prey to gimmicks and scams; two things that Boyd Rice indubitably has a (albeit, unconventional) talent for. Although I am far from flabbergasted by the fact that Rice cites Ray Kroc's Grinding It Out: The Making of McDonald's as one of his favorite books, I do find it extremely odd that he also referenced National Socialist philosopher Alfred Rosenberg's tome The Myth of the Twentieth Century and Francis Parker Yockey's magnum opus Imperium as major influences, as both works seem to fall out of line with the aesthetic terrorist's mostly materialistic weltanschauung. Indeed, Larry Wessel's Iconoclast is the most "epic" exposé of Boyd Rice's career, therefore, if you're looking to learn about the non-man; the documentary will provide you with a comprehensive portrait of his seemingly incomprehensible life. If you're already familiar with Boyd Rice and his career, you will find Iconoclast to be at least somewhat entertaining, yet it is doubtful the documentary will provide you with any new revelations regarding the film's subject. The most unusual aspect of the documentary is that it is an atypically sentimentalist look at an emotionally cold "Occult Fascist" musician, thus — more than anything — Iconoclast is a tribute to Boyd Rice and his loyal fans/supporters. Iconoclast is a testament to the fact that even Occult Fascists have feelings. For more info on Iconoclast, checkout Larry Wessel's official ICONOCLAST MOVIE website.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 30, 2011

6

comments

![]()

Saturday, May 28, 2011

Osou!

Yasuharu Hasebe is an "unsung hero" of the pinku eiga genre. With films like Rape! 13th Hour, Assault! Jack the Ripper, or the unpretentiously titled Rape!, Hasebe has carved a niche in which to rest surrounded by the most subversive sleaze to be found, all his own creation. Though not sleaze in the general sense of the term, most of Hasebe's films juggle what which most people refer to as "misogynistic" tendencies Osou!, for example, is the tale of Kumiko, a policewoman who is brutally raped by a strange attacker after an automobile collision. Not stopping with one count of sexual assault, the stranger returns time and time again to penetrate her at her most vulnerable moments, eventually reaching the point in which she wholeheartedly looks forward to their next rendezvous. It's not about the how, it's about the why. Osou! takes a woman and places her in such a situation. Libidinous to a fault, her own desires mesh with the savagery exhibited by her non-consensual lover producing a whole new woman. Ideally, you'd imagine that with the right treatment, a woman could adapt to a similar sexual situation, if not for consent than surely for instinct. Kumiko pines for violation by Osou!'s halfway mark. She is mesmerized by force and blunt seduction, which is not an uncommon fantasy for most women. It starts off simple with compliance towards biting, minor rough play, and the ever-effective hands-around-throat. Once the seed of obscure practice blossoms, a warmer reception may be held towards more extreme activities. This isn't misogyny in the slightest, it's evolution.

Before the audacious assault of a policewoman in a police station, Hasebe makes sure to pamper his actress with backdrops of thick concrete jungles for her to explore and enough motive to warrant the aggravated attacks committed against her. In a word, Kumiko is kind of a bitch. Had you ever had a run in with a police officer, I'm sure you've whined and complained about the balance of fair and unfair. Perhaps you were traveling 50 mph in a 40 mph zone - Mr. Important has got an important date to keep. Kumiko flips through her previous tickets to interrogate possible suspects and on her quest, apologizes to many people she may have wronged or been unfair to. A parking ticket certainly isn't grounds for bodily repossession, correct? For Hasebe, uniform is key to the eroticism within Osou!. Most males, hell, women too for that matter, admit to being aroused by uniform and costume in the bedroom. For this reason alone, Osou! inhabits the very core of eroticism in rape and not some far off filmic plane of exploitative trash and senseless buggery. The rapist assuredly is committing an illegal and unanimously frowned upon act but Kumiko takes it without principle, without morality. She sheds away the layers of incorrectness to find the heart of the act; pleasure. One might spite my words and cry offense to them but I'll have you know my words are no more offensive than the film they are in response to.

Sex follows Kumiko everywhere. Osou! is essentially an odyssey of sexual appetite. You'd swear angelic Kumiko hadn't an idea of the act with her tight and proper appearance. Once she is raped though, things swiftly change. Confronting possible suspects, she is seated inside of a car, conversing with a man she had ticketed previously as he has sex in close proximity. Following this incident, Kumiko decides to spend the night at her sister's house but is awoken by her sister's husband, as he ravages her body with his tongue. Aghast, the sister thrusts Kumiko out onto the streets with tears brimming in her eyes. This is a documentation of a woman uncovering the beastly side of Japan, no, men, as she is manhandled at every turn and thrown into dizzying sexuality. Definitely a strong film of Hasebe's, Osou! manages to help us discover what it means to hold onto that which fractures us. Once Kumiko begins masturbating, she comes to terms with her impure bits & bliss. Aiding the frenzied attacks is an array of strongly composed classical pieces that flutter closely over the head of the mysterious black-gloved rapist. One would expect to be averse to the rape, as it is an act of territorial noncompliance. However, Kumiko has the self-defense skills of a muzzled orangutan which leaves sympathy nowhere to be found. That's not to pull a card of natural selection, simply, it's too damn silly, her falling into the traps of a secret admirer almost repetitiously. Yasuharu Hasebe reigns king over this land of forced sexual encounters and there seems to be hardly anyone who can hold a torch to his objectifying of women. Osou! is a classic of his standard.

-mAQ

By

soil

at

May 28, 2011

14

comments

![]()

Executive Koala

When I look back at my life and ponder upon my larger regrets, never would I propose that I deserve this form of punishment. Naturally, cinema is one of my greatest passions, second only to sodomy. What cruel mistress would be foul enough in her arts to subject me to comeuppance in the form of cancerous filmmaking? Enter the films of Minoru Kawasaki, a Japanese director who panders around the very essence of Japanese culture perceived by Westerners - Namely, really cutesy "kawaii" plush furries and starry-eyed kaiju homages with an IV-drip of anime inspired machinations. Jumping in head-first, I honestly didn't want to know what a film starring a larger Japanese man in a Koala mask would entertain me with - the word entertain used very loosely. It just so happens that Executive Koala goes the way of dark comedy as we straggle behind a divorced salarykoala who begins to have bizarre flashbacks and memory lapses which lead him to conclude he is a sleepwalking murderer. Following the disappearance of his wife some odd years ago and now his girlfriend's bloody corpse, a detective trails behind Tamura, koala, and feebly attempts to find incriminating evidence. All the while Tamura creeps closer to cementing in a new, mysterious Korean client for his business firm.

Making a film like Executive Koala would be relatively simple, had you the willpower to capture motion video of less-than-savvy acting abilities and the awful motor-skills of a hybrid man-marsupial. It takes a true hack to twist the absurd into the unwatchable. Certain Japanese films, as tawdry as the may be, have the elements of train-wreck mixed with such unclassifiable material that it literally is damn near impossible to peel your eyes from the screen. Executive Koala certainly does not have this effect. Personally, I found myself in a room, wanting to be distracted by anything - a fly buzzing about the room, a phone call from someone I didn't want to talk with, even the mad rumblings of displeased bowels would have been welcome as opposed to forcing myself to be transfixed on what might be the worst film I have ever sat through, and to be honest, if I had known Executive Koala would end the way it did, I might have turned it off just to shatter the disc, to jab it straight into the jugular of the one who gave it to me. Minoru Kawasaki has created films similar to this, such as Calamari Wrestler and Crab Goalkeeper, in which he cuts and pastes a hybrid creature "seamlessly" into a world compromised of humanity. This makes for a silly marketing ploy to sell tickets. Executive Koala opens with a crudely animated introduction highlighting the cast of characters with a cheery song. Once the murder mystery actually takes place, you are immediately evidenced guilt as to Tamura being the killer. Certain kill scenes are composed of the victim facing a corner of the room while Tamura, facing the camera in grotesque close-up, strafes past the camera with inconsistently glowing eyes, obviously the results of a buggy animatronic koala head or the unmentioned fact that he is a cyborg. Do I even need to mention Tamura's inconceivable ability to teleport across the room on a whim? Never mind reality, Executive Koala is too insipid to waste your time defending it.

Few if any scenes within Executive Koala stand with purpose. Much of the runtime is dedicated to proving that Tamura is a skilled worker with an excellent ethic, yet demonizes his sanity and memory loss with instances of murder, only for the murders to have not actually taken place. Coincidentally a film is being shot of the same condition but it is never mentioned again after this initial scene. After the detective visits Tamura's village of birth, Executive Koala infuriates further with an amateur sing-and-dance number that includes getting final judgment from a fiery deity that I can only assume to be a dark lord. Executive Koala is many things - embarrassing, boring, entirely without charm - not to mention whenever a character is involved in physical combat, Minoru Kawasaki edits the character out and replaces it with a stuffed mannequin to get thrown and twisted to hearts content. Quirky and eccentric, somewhat, but that doesn't cover up the fact that Executive Koala is rookie garbage. No facet can be found enjoyable within the film and certainly not the physically harmful ending in which, after a dastardly cover-up, Tamura gets the girl, the detective forgets the crimes altogether, and they all stare at the sun in an equally disgusting pose - filled with inspiration and direction. I hate Executive Koala and so should you. If not for the incredibly stupid lack of "Koreagraphy" during the final fight than for the rest of the film, compromised of digital piss and shit, the likes of which entice me to punch my eyes out with a thin, blunt object.

-mAQ

By

soil

at

May 28, 2011

5

comments

![]()

Friday, May 27, 2011

Special Effects

The sleazy B-movies of indie horror auteur Larry Cohen have always intrigued me, but I have always found myself equally repelled by them in one way or another. From the venomous anti-Anglo hatred that permeates throughout his pseudo-blaxploitation (it is really an Aryan-ploitation work) flick Bone (1972) to the mind-numbingly blatant satiric anti-consumerism message of The Stuff (1985), Larry Cohen's pretensions towards making quasi-intellectual cult masterpieces is – to say the least – quite silly. The other night I had the opportunity to watch one of Cohen’s less well known works – Special Effects (1984) – an erotic psychological thriller that wishes it was Hitchockian in nature, but instead, it seems more like a rip-off of a rip-off, as if some totally mediocre filmmaker attempted to create a low-budget Brian De Palma clone. Despite the less than spectacular quality and special effects of Special Effects, I can say without straining my honesty that it is now my favorite Larry Cohen film. At the most superficial level, I enjoyed Special Effects because it features my favorite junky renaissance woman Zoe Lund. After first seeing Lund’s performance in Abel Ferrara’s Ms. 45 (1981), it didn’t take me long to realize that she was the most beautiful woman to have ever grace the torn screens of gritty grindhouse theaters. After all, most exploitation actresses are a dime a dozen with acting talents that fall below that of your average porn star (albeit, many were actual porn stars). Of course, I found Special Effects interesting for other reasons; namely the way in which Cohen seems to glorify the film’s villain; a filmmaker – who like himself – exploits the most archaic instincts of the viewer just to make an extra buck.

During the beginning of Special Effects, the viewer is introduced to psychopathic filmmaker Christopher Neville - a man who cites Abraham Zapruder – the man that accidentally documented the assassination of JFK with his handy 8mm camera – as his greatest influence as a filmmaker. Saint Christopher describes Zapruder as “honest Abe", but the filmmaker is not so honest himself. Neville – a man whose filmmaking career is on the steady decline – decides that killing a girl from the country (who he certainly sees as disposable white trash) and making a borderline Cinéma vérité film about the murder (replacing the girl's husband as the killer) will reboot his plummeting filmmaking career. Neville kind of reminds me of John Landis, as he also put people’s lives in jeopardy for the sake of making sensational smut. During the filming of Twilight Zone (1982), horror/comedy hack Landis caused the death of Vic Morrow (Jennifer Jason Leigh’s father) and two small Asian children due to his negligence while directing the film. Of course, in Larry Cohen’s Special Effects – the murderous filmmaker is fictional, yet it is quite apparent that Larry Cohen seems to sympathize with his anti-hero, as if he is living through his invented character. After all, Cohen surely does not identify with the intellectually handicapped female protagonist nor her idiotic (yet well meaning) Southern husband. Like Larry Cohen, the killer film director featured in Special Effects is also of the Jewish persuasion. In fact, Cohen equipped the film with insider Judaic dialogue. For example, the deadly director states at one point of the film (out of nowhere) to one of his film actresses, “Tell them you went to Israel to work in a Kibbutz or something.” Although Jerusalem is technically the Judaic capital of the world; the setting of Special Effects – New York City – is no doubt the unofficial Jewish capital of the world. The film also features a variety of Jewish stereotypes that would put most Nazi propaganda to shame. Filmmaker Christopher Neville demoralizes and enslaves every person that has the misfortune of crossing his conspiring path. Neville believes that the “glorification of a nobody” is what is hot in Hollywood and he plans to capitalize off of that trend. Neville also does not shy away from saying “murder, madness; that is what stars are made of nowadays.” As you learn in the film, Neville not only murders an ambitious actress, but he also frames the victim's husband – a good ol’ southern goy boy – into inheriting the blame.

Despite being a sub-par horror work, Special Effects – a film with a somewhat misleading title – still manages to titillate and invigorate the viewer. Thankfully, Special Effects lacks the intellectual pretensions that are so commonly associated with conman Cohen’s work. It is not often that one gets to see a film where Hollywood hack filmmakers are portrayed as parasitic pimps and enthusiastic murderers, thus, Special Effects makes for a fairly therapeutic and equally liberating work. In fact, Special Effects features a story worthy of Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon. Although Larry Cohen never obtained the real-life prestige that fictional psychopath filmmaker Christopher Neville acquired; he at least got the opportunity to live through that character via Special Effects. Unfortunately, Bone does not pay a visit to Christopher Neville, but, of course, he is a fellow defiler of white women, thus a man after his own heart. If you’re looking to watch a smashing and equally trashy kind of horror film, Special Effects will provide one with a special (albeit incriminating) experience for those that still doubt that lack of nobility that is the norm in Hollyweird.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 27, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Thursday, May 26, 2011

The Horseman

Ah, the fear every father adopts with the arrival of a newborn daughter - that his little angel will turn into an indifferent slut. Steven Kastrissios, a 26 year old first-time director, expresses and sketches similar fears in his ultraviolent "revenge" thriller, The Horseman. Constructed from the opening shot of the explosion of a degenerates home, The Horseman took flight once a short film of the matter was received well in film festivals. Acquiring budget and a further enraged vision, Kastrissios began to slowly stoke the fires under The Horseman, leading to a nice composition of heightening suspense and brutality. The Horseman is also quite a polarizing film, leaving many of the fence with its cruel depictions of humanity. Critics and audience members seem to either laud or loathe the sheer savage nature of this father's massacre as well as his intentions. Obviously titled from the idea of a harbinger of death and destruction but of mortal coil, Christian Forteski only sought solace from the mysterious circumstances of his only daughter's death. But when an anonymous source mails him a pornographic film entitled Young City Sluts and he witnesses his princess, obviously drugged, getting taken advantage of, Christian takes it upon himself to pursue and destroy the indirect attackers of his pride.

First off, you'll instantly notice a strong point of The Horseman is its seamy aesthetic of dimly colored grayscale. The Horseman's color palette mainly consists of shades of gray, complimenting the ashes of his daughter to which he seeks to spread somewhere on this barren and merciless rock. This decision to leave the colors dry and the lighting strong and natural makes for sickening detail to pores, sweat and other bodily fluids. The blood featured in The Horseman isn't bright red gush, rather, inky dark substance, quick to congeal and scab. A strange aspect of Christian's quest is what he seems to be killing towards; his confused motive. One would generally suggest to avenge the death of his daughter, but it doesn't seem to be the case with select scenes playing evidence to a hidden picture. Christian isn't killing for the sake of his deceased daughter - in fact, the only real memories he carries as baggage are flashbacks to her in her purest concentrate - toddler. He doesn't ponder thoughts of the rebellious years as a teenager or even preteen. Christian's wake of bodies is to cover the shame left by this creation of addiction. In desperate times, he even purchases every last copy of the film starring his lovely whore directly from the distributor for the sole purpose of destroying every last copy. Christian seeks out every last phallus that tasted the flesh of his bloodline to eradicate the trace of this smear on his good name. The presentation of the in-film film Young City Sluts is dramatic and dripping with enough fetish to warrant the suffering of the father - no lobotomized precursor to heroin fueled fucking. The Horseman is a very authentic experience in depravity, but at the same time, there seems to be no sense in mourning. Jessie is just another case of the father unable to control the wild lusts of his fledgling harlot. Along the way, a female mulatto hitchhiker is given a lift who reminds him of his daughter, though leagues ahead with this thing not common in women called "self-respect". Little does she know that her first-class accommodation is on a vessel that will inevitably lead her into the darkest crevices of desire and murder.

Quite evident of showmanship, The Horseman, like many other films, stutters near the final act with sensationalistic tendencies. What were once murders, individual, powerful, and unsettling, became something of a body count tally as Christian weaves through a compound leaving numerous corpses in his wake. If there could be one inspiration to cite it would assuredly be Joel Schumacher's 8mm - a tale of an investigator tracking down the source of a purported snuff film, though without the premeditation of murder at the hands of a grieving father. The action scenes tend to foster giggles as well, being shot in a very hyperactive fashion as to obscure impact leaving space for the lack of choreography to deceive. When Christian isn't tackling husky men to the ground and miraculously gaining the upper hand on them, he's committing various acts of genital torture. Such household instruments as fishhooks and tire pumps create harrowing expressions of pure agony. The Horseman is raw bodily nihilism with its perverse tortures and savage seduction. To continue the trend of dissecting the few flaws The Horseman carries would be to challenge the inclusion of the hitchhiker, who arguably only stands to be a crutch to cutting, an act of self-mutilation attributed mainly to teenage girls, which leaves Christian with some explaining to do. Ending on a note of helplessness and violation, the act that preceded the final images was above average at best but includes a scene of bone breakage that would leave any grown man wincing. I can't help but to still look up to The Horseman with stars twinkling in my eyes. Regardless of the faults, no blame can be directed as the feature is a debut work and inspired by anger so furiously, that I claw at the arm of my chair in anticipation of conflict.

-mAQ

By

soil

at

May 26, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Wednesday, May 25, 2011

Insidious

Abnormalities surround us. It seems to be life's way to stumble us upon "glitches". Couldn't this same concept apply directly to dreamscapes with a greater force of evil shadowing? James Wan's latest horror film, Insidious, attempts to salve the question, not with an answer, but with more questions. Being a fan of his earlier effort, Death Sentence, James Wan's keen eye for stark visuals and grain returns in Insidious but with less attention towards the grime and degeneracy but the sterility of a contemporary home setting. Turning the experience into a date movie of sorts, I tagged my ladyfriend along for the ride, for what I had hoped would at least be a thrilling, atmospheric take on hauntings. Paranormal films of the sort always seem to bore me. Flapping shutters and drapes dancing amidst light given off from a flickering flame is the concept. Insidious has defied the expectations of its stagnant wellspring and through a unique vision, supplied by Wan, unleashes a volley of consistent scares with some of the most alarming, disconcerting scenes of terror I have ever witnessed to this day. From the opening credits alone, trekking through a dimly lit house scored to screeching strings, I was mortified. When a single loathsome question returns, as it will time and time again, "what's the scariest movie you've ever seen?" - I now will have a fresh answer. Seated up there with select moments of Jacobs Ladder, The Mothman Prophecies, and the vagrant scene in Mulholland Drive, "Insidious is".

From the trailer, one surmises the boy to be a haunted vessel, which is a correct observation. It also serves as the tagline boasting the idea of a living being assaulted by spirits. Starring Patrick Wilson and Rose Byrne as the two tortured parents of a catatonic child, Insidious quickly sets up the structure of the important grieving parents. After falling through a ladder in a decrepit attic, Dalton passes off his concussion as nothing more and sets to slumber. When Dalton doesn't wake the next morning, the parents shamble to the hospital where doctors proceed to tell them that they don't exactly understand Dalton's condition. Cue the paranormal activities. What largely embodies the runtime of Insidious is seeping moments of dread that crawl across the screen. Sound plays an enormous part in providing chills. As mentioned before, wailing violins subtly scream during instances of duress. Barbara Hershey returns from her oppressive position as mommie dearest from Black Swan and adds empathy to the character pot, equating in one of the most shocking scares Insidious has to offer - during a sit down with the always-reluctant-to-believe father. The casting choice of Hershey was as if to conjure some of the magic seated in her incredible role in The Entity, and it works. Barbara Hershey was created to be haunted via screen and Insidious is the greatest love letter The Entity ever got, sans rape. Not even just for the comparable audible aesthetic of the two shocking films, Insidious jabs back with a story device of her knowing exactly what to do and claiming she's been through it before.

Before Insidious could possibly fry your circuitry with how intense the shocks are, James Wan makes a decision; a decision that almost ruined what was of the most frightful nature by morphing the finale of the film into something you'd expect in a M. Night Shyamalan picture post-Unbreakable. Mixing fantasy with the modern remnants of the roster of Thir13en Ghosts (personifying colored demons and phantoms), James Wan's Insidious starts harping the unreal, surreal elements of astral projection. Crossing thresholds of a misty nether, Patrick Wilson engages with spooky specters and demons that fancy the melodic neutered tunes of Tiny Tim - is the tune effective? Yes. All the while distracting? Of course. From here Insidious only gets worse and irredeemably silly. One can assume the scriptwriter himself suffered from a minor concussion as Insidious juggled terror so well only to fumble all of its hard work, spilling spherical shapes on hardwood floor. All is not poisoned, however. Insidious recovers its stance with a final hurrah, melancholic to the very core. When the proverbial day is done, Insidious stands with yet another recurring tool of horror; utilizing advantage against a mature demographic, their children, and making every sickly-sweet mother's toes curl against the auditorium floor. It is the same happenstance as my mother experienced when she watched Poltergeist all the years ago. Regardless of children being used as pawns in a small battle of good and evil and the various other contrived instances, Insidious is a fresh experiment in horror that proves there still are scares to be had. You might just have to strap your rain boots on to wade through the shit near the climax.

-mAQ

By

soil

at

May 25, 2011

1 comments

![]()

Lightning Over Water

Nicholas Ray was one of the few true bad boy directors that worked in the strict confines of the Hollywood studio system. Nick Ray directed Rebel Without a Cause (1955) – arguably the greatest and most influential teen angst film ever made – so, one could say that the Hollywood auteur invented the “too cool for school” model for misunderstood American youth . Ray also directed the subversive western Johnny Guitar (1954), a film that features Joan Crawford playing a cowgirl who can fight with the most brutal of cowboys, thus one could argue the director was a nominal feminist of sorts. Like most great directors, Ray’s talents started to dwindle as he entered his not so sparkling golden years. Due to being a lifelong drug addict and alcoholic, Ray started to find himself being rejected by the strictly business businessmen of tinstletown during the early 1960s. In fact, Ray collapsed on the set of his film 55 Days of Peking (1963) while intoxicated; no doubt one of the most embarrassing things that could happen to a serious filmmaker. If one thing stayed consistent in Nicholas Ray’s life (besides constant intoxication), it was his ability to fit in with and influence younger generations of filmmakers and actors. Ray is known for being extra considerate to the stars of Rebel Without a Cause, even allowing James Dean to give much creative input in the direction of the film (some have argued that Dean actually directed the film). In 1970, Ray met and smoked weed with the equally eccentric Dennis Hooper (who had a small role in Ray’s Rebel Without a Cause) during a Grateful Dead concert at the Fillmore East in Manhattan, NYC. At the time, Hopper was putting the finishing touches on his cinematic bomb The Last Movie (1971). Not long after the concert, Hopper landed Nicholas Ray a film studies professor job at SUNY Binghamton University in upstate New York. Just as he did with Hopper, Ray had no qualms about smoking weed with his film students. In fact, Ray and his students can be seen sharing a joint together in the director’s last work We Can’t Go Home Again; a film that the filmmaker worked on for about a decade, but never officially completed (although rough drafts of the work were screened at various film festivals). In the documentary Lightning Over Water (1980), German director Wim Wenders captured Ray’s remaining days on earth.

Seeing as I am a fan of both Wim Wenders and Nicholas Ray's films, I expected Lightning Over Water to be a an oh-so rare work where two different directors from two different generations and two different worlds come together for a special moment in cinema history. Instead, Lightning Over Waters was one of the most painful and unrewarding films that I have had the displeasure of seeing. Basically, the documentary is about an arrogant young auteur who coldly documents the depressing deterioration of a once virile and rebellious filmmaker. Ray may have smoked pot and guzzled booze well into his senior years, but in Lightning Over Water he can barely even string together a simple and articulate sentence. During the beginning of this quasi-documentary, Wenders oddly states to mentally and physically gray Ray, “I thought I’d find myself attracted to your weakness and suffering.” Indeed, it does seem like Wenders is deriving pleasure from Ray’s mental and physical decline throughout Lightning Over Water. Although Lightning Over Water is a documentary, many of the scenes seem rather staged and horribly contrived, as if Wenders was attempting to make a minimalistic melodrama, but neglected to include a cohesive plot. If there is one elment about the film that is truly authentic, its Ray’s delirium and dementia-ridden-like behavior. At one point in the documentary, Ray states, “Jesus Christ, I’m sick!”, yet it still seem as if he can’t completely understand what is happening to him. I am sure that Ray’s lifelong hedonistic pursuits had worn his health to nil, though he still seems like the typical kind of elderly person that you can easily find at a full-care nursing home. Anyone who has ever watched a grandparent lose their health knows that it is not the most pleasant event to witness. If Wender’s manages to do anything right with Lightning Over Water, it is documenting the all-encompassing melancholy and misery that often accompanies old age. I seriously doubt that the majority of serious cinephiles (be they fans of Ray and/or Wenders or not) while find any redeeming qualities - whether it aesthetically, thematically, or historically - in the entirety of the film. Despite being packed with gloom and hopeless despair, Lightning Over Water also manages to be extremely banal and quite the struggle to get through. The fact that the film – a highly intimate and extremely serious work – was screened out of competition at the 1980 Cannes Film Festival just goes to show how horrible of a film it really is. After all, if Lightning Over Water was at least half-way decent, the judges probably would have given it honorary critical acclaim due its seemingly human portrayal of a once highly influential filmmaker. Wenders even failed to make the documentary a worthy tribute to Nicholas Ray’s filmmaking career. Lightning Over Water does feature a couple snippets from Ray’s large body of work, nevertheless, these scenes are completely bombarded and ultimately eclipsed by the filmmaker’s stark geriatric degeneration; making it seem as if his entire filmmaking career was solely in vain. Although a lot filmmaker’s experience a wane in artistic prowess as they reach old age, few filmmakers have concluded their career with a project that is as repellent and uncomplimentary as Lightning Over Water.

Nicholas Ray and James Dean

I am not one who tends to label films exploitative, however, Lightning Over Water is blatantly so. For Wim Wenders to claim that Nicholas Ray was a great friend seems a little more than dishonest. In a perfect world, Ray’s career would have ended with the successful completion and critical acclaim of We Can’t Go Home Again, but instead, his life concluded with the deplorable and disposable abortion Lightning Over Water. Of course, it will be superlatively obvious to most viewers that Wenders' self-satisfied sadism bleeds throughout the entire documentary. For most of Lightning Over Water, Wim Wenders looks like a wimpy prick full of pretention and anal retention as he creepily and somewhat fiendishly lurks around the mostly oblivious Nicholas Ray. Near the conclusion of Lightning Over Water, Wenders forces Ray to call the cut of the film. Ray – being in an overt state of confusion – somewhat agitatedly, yet appropriately, responds with, “I am sick and you’re making me sick………..ok I’m finished.” It should also be noted that Lighting Over Water was directed and narrated in a manner comparable to a Werner Herzog documentary; minus character and spirit. Whereas Herzog's documentaries are know for being quite empathetic and respectful in their portrayal of (often peculiar) subjects, Lightning Over Water offers an impudently aloof and aweless depiction of Nicholas Ray. Although I have enjoyed some of Wim Wenders' films in the past (Wings of Desire and Paris, Texas), I would be lying if I did not admit my newfound disdain for the obnoxious German auteur. Maybe if Wenders is lucky, some young and obscenely arrogant up-and-coming filmmaker will document his remaining days on his deathbed in a manner as vulgar as his putrid portraiture of Ray in Lightning Over Water. Near the beginning of the documentary, Wenders mentions the budget he has to work with for an upcoming film; to which Nick Ray responds with, "For 1% of that, I could make………………….. lightning over water." Unfortunately, Wim Wenders was the one that made Lightning Over Water; a film less appealing than cute piglets being led to their slaughter.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 25, 2011

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, May 22, 2011

Missoni

Although I thought Kenneth Anger had given up on creating the kind of extravagant and boldly colorful surrealist works that were typical of his past films for more minimalistic and less labor extensive works, he has thankfully astonished me with his 2 ½ minute short Missoni (2010). Aesthetically, the short echoes back to the dreamy decor featured in Anger's Puce Moment (1949) and the psychedelic kaleidoscope of colors prominent throughout Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954). Luckily, the prestigious Italian fashion house Missoni hired Anger to direct this short as a fresh and stupendous way to advertise their 2010 collection. Its seems that as of lately, Anger has been landing many of his filmmaking jobs from advertisers as the director also created the 42 second short Death (2008) for the vodka brand 42BELOW as part of their OneDreamRush film compilation; a cinematic anthology that also includes works by fellow subversive filmmakers like David Lynch, Harmony Korine, Larry Clark and Gaspar Noé. Naturally, Missoni is more intoxicating than any vodka drink could ever be and one will fail to receive a killer hangover after watching the lucid and colorful short. As one would expect from the artistically audacious Italian fashion house; eleven members of the Missoni family modeled their own creations for Missoni. I wouldn’t be the least bit surprised if the Missoni designer clothing featured in the short was in one way or another inspired by those wardrobes featured in past films directed by Kenneth Anger. As it typical of an Anger film, Missoni features an equally hypnotic and complimentary soundtrack that is sure to draw the viewer in; whether they want to be under the spell of the Lucifierian filmmaker or not. Missoni's score – which was composed by the French group Koudlam – sounds like an ambient neo-darkwave track. After initially viewing the short, I had no idea what it was supposed be about (but I was still completely enamored by it) and I certainly did not suspect that it was part of a marketing campaign. For those (myself included) that were under the terrible impression that Kenneth Anger may have lost his moviemaking magick, Missoni makes for a soothing and ecstatic awakening.

Despite being an advertisement, it seems that Kenneth Anger has equipped Missoni with occult symbolism. Considering that I am far from a Crowleyite, I have no idea what the esoteric messaged contained within the short means, but I am sure that it is clever. With Missoni, Kenneth Anger once again proves why he is one of the few modern filmmakers who can be compared to such pioneering directors as F.W. Murnau and Carl Th. Dreyer; as the short's mise-en-scène is as intricately and expressively assembled as one would expect from the canvas of a master painter's work. Indeed, Missoni is a hallucinatory collection of sinister, yet spectacular holograms that were designed with the utmost precision by an auteur with an irreplaceable vision. The fact that Missoni was created in Italy only makes it all the more fascinating. After all, Anger’s spiritual father and metaphysical guru guide Aleister Crowley was expelled from Italy by Il Duce Benito Mussolini, yet the American themelite auteur was welcomed to the country as a serious artistic celebrity. Instead of fascist propaganda, modern rich Italians with disposable incomes now have the honor of being subconsciously brainwashed into buying overpriced wardrobes via the cine-magick talents of svengali auteur Kenneth Anger. If anyone doubts Anger’s authentic talents as a magician with an otherworldly vision, one just has to blissfully bask in the minute phantasmagoric motion-picture dream Missoni; a film that proves not all advertising and subliminal messages are bad. It is undoubtedly a sad time in cinema history when a 2 ½ minute fashion advertisement directed by an elderly man (albeit a cinematic genius old man) has more artistry than the majority of independent films that have been released since the new millennium. I just hope that Kenneth Anger has the opportunity to direct more shorts like Missoni in the future for if he were cease to concoct such majestic works,I would indubitably suffer from a long-drawn-out case of cinephile torture.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 22, 2011

2

comments

![]()

Wednesday, May 18, 2011

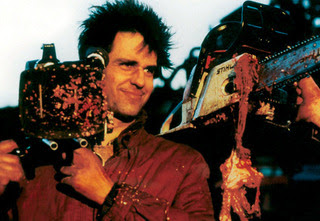

The German Chainsaw-Massacre

The German Chainsaw-Massacre opens with real-life documentary stock footage from the 1990 German reunification ceremony. Then, the film takes a sinister turn for the worst, warning viewers that east Germans - who look and act like westerners – are secretly living among them. During the Third Reich, Aryan blood was considered nothing short of holy, but in GCM it is merely a less than meaty lucrative means for maniacally making money. Additionally, while the Teutons of Nazi Germany wanted to consolidate with their racial brothers from around the world, most of the eastern and western Germans featured in GCM much rather prefer murdering one another. It goes without saying that GCM and TCM also have their differences. Whilst the slightly deranged cannibalistic Sawyer family featured in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre prefers only the finest grade human meat, the west German human-butchering clan of The German Chainsaw-Massacre stereotypically prefers Teutonic bratwurst cut from the cheap meat of east German swine. Of course, that is not the only difference between the two families, as while the quasi-inbred Texan Sawyer family prefers to butcher and sell the meat of counter-culture hippie types, the family featured in GCM – who are set in their barbaric ways – are happy to kill friendly progressive east Germans, as they make for tasty would-be cosmopolitan treats. Thus, it is apparent that Herr Schlingensief executed a role-reversal tactic with his distinct brand of chainsaw massacring - portraying the seemingly more advanced west Germans as debauched capitalists who are too set in their greedy ways to reunite with their culturally and economically bankrupt kinsmen. Even to this day – like most ex-Soviet eastern bloc nations – the eastern region of Germany still hasn't recovered from decades of communism. Of course, in Hooper's The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, the director played on the prejudicial fears many Americans have for "backwards", "inbred" and "violent" confederates. As you find out during the beginning of GCM, east German anti-heroine Clara is far from being a sweet sassy lass as her thirst for blood is almost equal to that of the west German cannibal clan she falls prey to, for she is an undeniably proficient killer with an improvised talent for murdering and castrating enemies. While portraying those east Germans who refuse to leave their post-communist region as backwards automatons who are incapable of deracinating themselves from their former authoritarian brainwashing (as personified in GCM by a group of emotionally robotic ex-Stasi border patrol guards), the progressive west Germans - who are also set in their (materialistic) ways - slaughter their countrymen for blood soaked meat and Deutsche Marks. Frau Clara is indubitably a progressive feminist that yearns for total freedom as her sole interest is to emigrate to the west at any cost, even if she has to murder her androgynous troll-like husband in the process. On top of featuring a totally different socio-political subtext from the more traditional and linear horror history told in The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, The German Chainsaw-Massacre – a salacious work of unconventional slapstick murder – features gore-galore and endless scenes of exquisite entrails and bodily dismemberment. Like most of Christoph Schlingensief’s work, The German Chainsaw-Massacre is first and foremost a clever (albeit intentionally trashy) neo-surrealist romp satire that should be taken solely in jest. Every serious horror fanatic knows that Hooper’s cannibal clan flick is a canonical masterpiece of the macabre (as advertised in the film) due to its extremely naturalistic and somewhat cinéma vérité inspired aesthetic, thus, I suspect that the most fans of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre will fail to appreciate (nor begin to understand) the wickedly designed jubilant chaos that is The German Chainsaw-Massacre.

I have a feeling that Christoph Schlingensief was less than enthusiastic about splatter films, but he certainly proved his profound understanding of the horror subgenre through the satiric tongue-and-cheek nature of The German Chainsaw-Massacre. Although the film features enough gore to stun the most desensitized of gorehounds, it will be apparent to those individuals that the director lacks respect for such exploitive exploits. In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if Schlingensief was mocking Jörg Buttgereit’s Nekromantik (1987) – which was released a couple years before The German Chain Saw Massacre – as both films feature mangled human torsos (both being the result of an automobile) that look quite similar. GCM is like a perfect marriage between the Viennese Actionist films and the surrealist works of Luis Buñuel confined to production values that mirror John Waters' early Art-House-Trash flicks (Pink Flamingos, Desperate Living, etc.). Also, despite the sexually surreal nature of The German Chainsaw-Massacre – which includes incest and female-on-female missionary style rape – it is quite apparent that Schlingensief is mocking the post-WW2 libertine nature of European cinema. To put it simply, The German Chainsaw-Massacre is one of the ugliest and most revolting films that I have ever seen in my cinema-obsessed life. What saves GCM from being a loathsome pile of Germanic excrement is how hilarious and audaciously ridiculous the film is. Thankfully, Christoph Schlingensief was a politically astute individual who knew how to make his atypical symbolic social commentary digestible. After all, most politically-charged filmmakers are quite obnoxious (Spike Lee, Michael Moore, etc) in their execution of socio-political commentary. It is very doubtful that there exists another film in the world such as GCM; where a cannibal family keeps their dead Wehrmacht soldier grandfather (symbolic of Germany's inability to move forward) as a mobile shrine (another nod to TCM). To call the films of Christoph Schlingensief difficult would be an obscene understatement, but for those that have the gall to visually devour works that blur the imaginary line between pure trash and pure art, his films offer cinematic experiences like no other. Although A Hundred Years of Adolf Hitler (1989) is the first film in the director’s “German Trilogy”, I recommend that Schlingensief-virgins watch The German Chainsaw-Massacre first as it is a much more accessible work. Due to Hollywood and the mainstream (and the not so mainstream) media’s skillful knack for inducing Teuton-phobia in the minds of American citizens, I think that is safe to say that it if the average yank were to watch one of Schlingensief’s films, it would (mistakenly) confirm their suspicions regarding the purported dubious nature of the fallen master race. Luckily, Schlingensief’s films are only known and beloved by a small cinephile elite that cherishes the unfortunately deceased auteur filmmaker’s incomparable works of post-post-modern Germanic anti-kultur. Maybe someday a brave American horror auteur will do for Amero-cinema what Christoph Schlingensief did for German national films, but such an unlikely scenario is merely wishful obsessive-cinephile thinking. Instead, next time I watch The German Chainsaw-Massacre, I plan to accompany it with The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, as such an eclectically perverse double-feature could only make for an oh-so rare majestically macabre experience. German prophet philosopher Oswald Spengler once stated something along the lines that out of all the artists (he was most specifically referring to the German expressionist painters) who created art during the interbellum period (between the first and second World War), not one of them was an artistic genius that had the ability to construct aesthetically pleasing works. That being said, Spengler was lucky that he didn't live to see the subversive works of post-WW2 German filmmakers. Spengler – whose canny physiognomic tact enabled him to foresee many of the horrors that would occur in the western world nearly a century after his death – couldn't even have foretold the spiritually sick chaos contained within a hyper-cynical film like German Chainsaw-Massacre. Since we (the living) are all confined to culturally degenerate times – where art is more often unprepossessing than not – one might as well buckle-up and enjoy the deluging ride. Whether you were born in Germany or not, one (most imperatively those of occidental heritage) should accept that a film like The German Chainsaw-Massacre is mostly importantly a reflexive sign of our wretched times.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 18, 2011

2

comments

![]()

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.