-Ty E

Tuesday, June 26, 2012

Daddy

Despite my general disdain of virtually any and everything relating to feminism, sexual ‘liberation’, and gender politics, every once in a while I find myself exceedingly – if mostly unintentionally – amused by pretentious works of art of this thoroughly deplorable persuasion. Most recently, I had the distinct (dis)pleasure of viewing the man-hating quasi-Freudian film Daddy (1973) directed by Franco-American feminist sculptor Niki de Saint Phalle and British documentarian Peter Whitehead (Charlie is My Darling, Benefit of the Doubt); a work of degenerate-art-gone-awry yet somehow done somewhat accidentally right, but for all the wrong reasons. Although co-directed by Whitehead – a filmmaker best known for documenting the London and NYC counterculture scenes of the late 1960 and creating proto-music-videos for groups like Pink Floyd and The Rolling Stones – Daddy is essentially an embarrassingly intimate and incestuous, as well as contemptuous and sadomasochistic (un)love letter to Saint Phalle’s unfortunate father. Whitehead originally intended to create a documentary about Phalle and her artistic works, but this idea later dissolved into what is one of the most glaringly grandiloquent and inadvertently ludicrous films ever made. Best known for her mostly aesthetically displeasing sculptures (including a horrid blob-like Golem statue located in Kiryat Hayovel, Israel) and paintings, Daddy features many of Niki de Saint Phalle’s childlike artistic creations in various forms, which do a splendid job accentuating the would-be-audacious auteur essence of her discombobulated mind and schizophrenic Electra complex. From the very beginning of Daddy, it is most apparent that Saint Phalle both adores and abhors her dear dad and his pesky philandering phallus. As a daughter of a French banker, Saint Phalle created a rare work that expresses the downright petty personal problems of a spoiled bourgeois debutante whose starvation for attention is played out in such an absurdly hyperbolic and hysterical manner that one would think assume she survived a famine; or at least an overextended third world mass gang raping. In short, Daddy is a patently pathetic and erratic exposition of what it means to have never struggled in one’s life and the rare neurosis such a lavish yet unnatural la-di-da upbringing sows.

Featuring giant cocks in coffins, buckets of blood and naked voluptuous beauties on altars, and elderly pseudo-aristocrats in pancake makeup and drag, Daddy is a decadent daydream for the more debauched members of the blasé bourgeois. Of course, if one can look past the putrid pettiness of Saint Phalle’s next-to-nonexistent personal problems, Daddy makes for an engaging and curiously worthwhile cinematic effort. Divided into chapters by Phalle’s toddler-esque color drawings, Daddy feels like a Victorian Gothic kitsch piece directed by posh preschoolers, except ridden with mostly distasteful fetishistic sex scenarios that would probably only interest demoralized bluebloods and novice swingers. In fact, I would argue that Daddy is like an Alberto Cavallone (Zelda, Blow Job) film had the Italian director taken himself too seriously, and lost his technique and sense of humor, but I guess that is what one would should expect from an ostensibly discordant collaboration between a feminist erotomaniac and an uninspired hippie documentary filmmaker. Lacking any true daughterly affections for her cold, collected, and cunning father, Saint Phalle channeled these eternally desired but never consummated suppressed emotions into an unhealthy and pathological sexual form, thus enabling her to identify with the unloving fornicator and misogynist whose semen she was spawned from on some level; no matter how utterly base, socially taboo, and exceedingly revolting. To appease the bestial appetite of the man whose attention she hopelessly sought, the woman even offers her dandy-like daddy a virginal vixen in between sexually degrading him in a variety of perversely infantile and unequivocally vulgar ways. Needless to say, Daddy is the sort film Sigmund Freud would have lauded as it plays out like one of his fantasy-inspired theories; or would have at least provided him with a masturbation aid. Narrated in an incautiously contrived and ridiculously wooden manner and performed by a cast of incompetent non-actors, Daddy is a work that even Camille Paglia couldn’t have sit through without smirking snidely, yet these flagrant flaws also act as some of the film's greatest and most idiosyncratic attributes.

Although Saint Phalle attempted to reject the conservative values of her family, even causing her kinfolk to decry and shun her art in the process, she inevitably ended up marrying and becoming a mother at a relatively young age, thus turning into her own worst enemy and eventually suffering from a nervous breakdown of sorts. After watching Daddy, I was not the least bit surprised to learn of Saint Phalle’s seemingly hypocritical destiny as her love-hate relationship with her family – most specifically her father – seems so deeply enrooted in her being and artistic creations as expressed so vividly in Daddy that deracinating herself from it could have only resulted in a much more extreme and detrimental psychological break. Whatever I may think of the quality and beauty (or lack thereof) of her art, I do believe that Daddy is a true and genuine artistic expression of the artiste, even if created by a somewhat soulless woman (or an emotional retard if you will) who was probably given more pet ponies than hugs as a child. If there is a film that boldly yet disastrously expresses the stereotype that feminists are often inspired to adopt their ideology due to having weak and decidedly detached fathers, it is incontestably Daddy.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

June 26, 2012

5

comments

![]()

Sunday, June 17, 2012

Nightbirds

Until last week, I thought Andy Milligan was one of the most irredeemable, talentless, and inconsequential filmmakers who had ever made the unfortunate mistake of picking up a Bolex 16mm camera. The fact that he has a marginal but loyal following baffled me as most of his inept cinematic works would not even be worthy of a minor Troma direct-to-video release. Of course, that was before I saw his extremely sordid yet queerly charming x-rated anti-romantic drama Nightbirds (1970); a mostly unseen work that was once considered lost until Milligan biographer Jimmy McDonough revealed a 16mm print of the film that he would later sell to Danish auteur Nicolas Winding Refn (Valhalla Rising, Drive); who would later help with the restored release of the film (with Milligan's campy vampire flick The Body Beneath) on dvd/bluray by actively petitioning the British Film Institute (BFI). If it hadn’t been for Refn’s serious commitment as both a filmmaker and a cinephile, I am fairly certain that I would have never attempted to watch another Andy Milligan smut-piece again after my last grueling experience with his appropriately titled yet surprisingly banal work Fleshpot on 42nd Street (1972). In fact, the sole reason (aside from a recommendation by Phantom of Pulp) why I decided to give Nightbirds a chance was due to Refn’s name being on the front cover of the new BFI release because, unlike unrefined cinephile Quentin Tarantino, the Danish auteur filmmaker is someone whose taste in cinema I can trust and count on. Indeed, Nightbirds proved to be a magnificent piece of gritty melodramatic misogyny that totally took me by surprise; so much so that I ended up watching the film no less than three times over the course of a one week period. I don’t know whether or not Milligan was experimenting with a different kind of drug, amidst a breakup with his latest boy toy, or emotionally influenced by the wet and dreary London air, but with Nightbirds he proved that behind all the vapid degeneracy and technical incompetency was a serious and uncompromising artist with something profound yet inordinately pessmistic to express, even if it was a stereotypically gay contempt for womankind and heterosexual love. Mr. Refn stated of maniac Milligan: "He was sort of a Douglas Sirk figure." Indeed, Nightbirds is a quasi-Sirkian work for degenerates, delinquents, dandies, and other socially defective individuals that makes Todd Haynes' Sirk-inspired work Far From Heaven (2002) seem quite restrained and prosaic by comparison. Nightbirds follows the spontaneous and aimless rise and deadly fall of an ephemeral relationship between two lanky British blondes: Dink (Berwick Kaler) and Dee (Julie Shaw). Right from the beginning of Nightbirds, it is blatantly apparent that goofy momma’s boy Dink is submissive to all of Dee’s self-indulgent desires. Sensing and eventually exploiting his kindheartedness and gentlemanly demeanor, Dee – an opportunistic succubus who uses her beauteous body as a man-eating weapon – takes Dink’s heart hostage and drains his feeble soul. Squatting on the top-floor of a decrepit apartment building owned by a young slumlord named Ginger, the twosome spends their days and nights having mostly one-sided impassioned sex, but unlike kindly Dink, Dee has no other expectations nor desires for a relationship other than erotic debauchery where her body is treated as a precious temple of worship and her groveling man is nothing more than a glorified vibrator with arms and legs that makes whining noises.

Like the equally unseen and shameless British film Duffer (1971) directed by Joseph Despins and William Dumaresq, Nightbirds is a gloomy and gritty work depicting the peculiar perversity of the non-working urban proletariat. Neither Dee nor Dink were born in the working-class, hence their abhorrence of work and failure in regards to self-sufficiency. Unable to deal with the neurotic ramblings of his distraught widowed mommy, sweet and humble man-child Dink chooses homelessness over reasonably plush bourgeois comfort and eventually bumps into ferocious femme fatale Dee by mere chance, thus beginning their manifestly foreordained relationship. Leading desultory lives with nil goals for the foreseeable feature, the curious couple of Nightbirds sees nihilistic sex as a way of life and working and building a family as a gross pestilence. As a socially retarded would-be-romantic at heart, Dink is willing to overlook the fact that his quasi-sociopathic girlfriend is an unsentimental ice queen of the most unrelenting and thoroughly demoralized kind. In his pathetic and ultimately self-destructive naivety, Dink is willing to do anything and everything to please his idolized girlfriend as long as it does not involve working, including grovelingly kissing her feet and performing cunnilingus on Dee's command and masochistically accepting her venomous verbal reproaching, whilst totally oblivious to the fact that Dee sees him as nothing more than a momentary fling and a semi-entertaining sexual novelty. Unable to provide for himself, let alone his girlfriend, Dink relies on Dee’s crafty flirtations with other men and shoplifting to survive. Essentially, Dink and Dee – as a product of the post-WW2 generation – are an unstable couple that are totally at odds with every characteristic that was once expected of traditional and healthy western societies. Naturally, the couple would also feel at home in the sort of degenerate hipster ghetto microcosm of false values mindless sex, drugs, and rock 'n' roll contained within the early cinematic works of Paul Morrissey. Unlike Morrissey’s pseudo-cinéma vérité works Flesh (1968) and Trash (1970), Nightbirds has a fairly potent, penetrating and expressive atmosphere, even if most of the film is constrained to a single and relatively unfurnished room. Originally shot on grainy greyish 16mm film stock, Nightbirds – like Duffer – is as aesthetically dispirited and decayed as it is thematically, thus near-perfectly accentuating the lifelessness of the demoralized characters and post-industrial setting the film so candidly portrays. Nightbirds also features a sometimes erratic and disjointed editing style that is analogous to the despoiled psyches of its lead characters. Needless to say, Nightbirds is a film that will appeal more to antinatalists than hopeless romantics.

Like Andy Milligan’s first film Vapors (1965), Nightbirds is considered to be one of the hysterical homo auteur filmmaker’s most personal and unprecedented efforts, sort of like Fassbinder-meets-grindhouse-kitsch. As a rabid misogynist who was raised an exceedingly cold and emotionally and physically abusive alcoholic mother, Nightbirds features one of the most naturalistic and inexorable depictions of a vicious vixen of a woman ever captured on 16mm film. Although evidence of Dee’s sadistic personality is sprinkled throughout Nightbirds, it is not until the remaining minutes of the film that one learns the true extent of her utter soullessness and sheer depravity. Like all great exploitation works, Nightbirds features a tragic conclusion that is guaranteed to fully agitate less than demanding filmgoers. Although featuring scenes of sex and nudity throughout, Nightbirds is about as erotically stimulating as a vintage Polaroid of Steven Spielberg in a bikini and as romantic as a winter season coathanger abortion. I can honestly say that Nightbirds is one of few films that has inspired me to reexamine the work of a director that I was once vehemently dismissive of, so if you're an Andy Milligan virgin, make sure that you pop your cherry with Nightbirds. For an auteur that boasted of never directing a film that cost over $10,000.00, Nightbirds is certainly no small achievement.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

June 17, 2012

3

comments

![]()

Tuesday, June 12, 2012

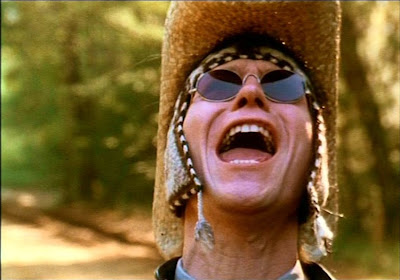

Track 29

Out of all of his many experimental and distinctive auteur works, Nicholas Roeg’s drama-fantasy-horror hybrid Track 29 (1988) is very possibly the English filmmaker’s most singular, inscrutable, and artistically ambiguous work, even if it is his least technically innovative. Co-produced by George Harrison of The Beatles fame and penned by English screenwriter Dennis Potter, Track 29 takes an outsider (aka liberal Brit) look at a small American Southern town in a most contemptuous and unflattering way. Starring Roeg’s cat-eyed ex-wife Theresa Russell (Eureka, Insignificance) in the lead role, Track 29 is a work centering around a mentally-unstable and under-sexed alcoholic housewife named Linda Henry who receives a surprising visit from a young eccentric British hitchhiker named Martin (played by Gary Oldman) who purports to be the son she reluctantly put up for adoption as a scared teenager. Fed up with her pretentious yet eccentric philandering surgeon husband Henry (played by Christopher Lloyd) – who has a peculiar duel fetish for masochistic spankings and model trains – Linda begins to embrace the loony leprechaun of a man that is apparently her long lost sole progeny, but unfortunately for her, he may be only a figure of her distorted imagination. While her hubby Henry is off getting routine spankings at work from his beak-nosed mistress nurse Stein (played by a young yet still considerably repulsive Sandra Bernhard), Linda enters the mysterious world of incestuous family bonding with her man-child son; a hyperactive and high-strung lad who feels that being a coddled grown-up toddler is an ideal career move. Noticeably scarred by his abandonment as a child, Martin inevitably has a terrible temper-tantrum and takes out his pent up rage on Henry and his extravagant model train set in this extremely loose reworking of Oedipus Rex.

It should be apparent to most viewers of Track 29 that Nicholas Roeg is not exactly sympathetic towards the inhabitants of the small Southern town that he depicts in the film. In fact, not a single character in the entirety of Track 29 is remotely likable. One can only assume that Roeg was pompously sneering at the fictional degenerate confederate Anglo-Americans characters that he so brazenly concocted throughout the production of Track 29. Many of the characters and scenarios played out in the Track 29 would be at home in David Lynch’s Twin Peaks. Indeed, I would go so far as to say that Track 29 is a work that is probably more of interest to Lynch lovers than fans of Roeg’s previous work. Although missing Roeg’s signature choppy deconstructed narrative montages, Track 29 does features a couple Lynchian flashbacks that scream rustic surrealism and oddball clodhopper perversity, which is undoubtedly the English filmmaker’s prejudiced vision of the American South. Right from the get go of Track 29, it is most apparent that Linda is the no longer desired trophy wife of her intellectually superior husband Henry; a man whose sense of superiority over his spouse is quite glaring to the point where he barely sees the need to conceal his preference for toy trains and his less than homely Hebraic mistress. Linda, being of a more conventional sexuality, fantasies about her Daddy but eventually settles for her overly sensitive son; a fellow who is quite conscious and equally vocal about his overwhelming Oedipus complex. Only through her son (whether he be real or imaginary) can Linda expel the "inner demons" of her fragile mind and rid herself of a soulless man who sees her as nothing more than blatantly inferior aesthetically-pleasing white trash. Despite the mostly obnoxious and otherwise loathsome nature of the main characters in the film, I was reasonably impressed with all of the lead performances featured in Track 29. I tend to think of Theresa Russell as a savvy and sophisticated seductress so it was nice to see her play against character as a psychosis-ridden philistine with a self-destructive drinking problem. Additionally, I have always found Christopher Lloyd’s iconic character roles in the Back to the Future trilogy and The Addams Family films to be patently exasperating, so I certainly welcomed the unwavering chutzpah and gross infidelity of his character in Track 29. Of course, out of all the performances featured in the film, Gary Oldman deserves the most praises for his willingness to hop on Christopher Lloyd whilst au naturel, on top of acting like an all-around retarded rug rat throughout Track 29.

At the conclusion of Track 29, many questions are left unresolved; hence the general mixed feelings towards the film among Nicholas Roeg fans and general viewers alike. For me, Track 29 is an abominable portrait of Americana that keeps on giving with subsequent viewings due to its lack of resolve and overall incoherence. Whether Track 29 is a dream-within-a-dream, a series of alcohol-induced illusions, and/or a semi-surreal depiction of reality is up for speculation, but I certainly consider the overwhelming ambiguity of the film's storyline to be one of its finest assets. After all, being that Track 29 is an intemperate celluloid psychodrama of sorts that depicts the lifelong trauma a woman suffers from after being brutally deflowered by a bestial carny, one can only expect a certain amount of rationality for such a work. It should be noted that Martin himself takes on the appearance (even featuring the same trashy Mother tattoo sprawled across his chest) and wardrobe of his hillbilly father, who he actually meets while hitchhiking during the beginning of Track 29. For Linda, Martin is a dichotomous symbol for her greatest dreams and worst nightmares; the son of the man who would not stop when she said "no" during sex, but also the man that gave her carnal pleasure and her only child. It is only when she comes to terms with these conflicting emotions via Martin that she can move on with her life. Needless to say, I think that rape victims should approach Track 29 with the utmost caution.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

June 12, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Monday, June 11, 2012

Mondo Weirdo: A Trip To Paranoia Paradise

Although I find both filmmakers absurdly overrated in their own respective ways, I could not help but be intrigued by a film that opens with the seemingly nonsensical and equally pretentious inter-title, “dedicated to Jess Franco & Jean-Luc Godard.” The film in question is Mondo Weirdo: A Trip To Paranoia Paradise (1990) aka Jungfrau am Abgrund aka Virgin on the Edge aka Virgin at the Abyss directed by Carl Andersen (Vampyros Sexos). Despite the (thankfully) misleading title, Mondo Weirdo is not another mundane mondo movie, but it does feature a wealth of demoralizing sleaze and exploitative nudity, at least certainly more so than one would typically expect from a standard work of the mostly asinine pseudo-documentary subgenre. Instead, Mondo Weirdo is an almost feature-length (at approx. 54 minutes) arthouse splatter-porn flick from Uncle Adolf’s homeland of Austria that is in welcome schitzy-kitschy company with Demetri Estdelacropolis's Freud's Flesh & Mother's Meat (1984) and Fred Halsted's The Sex Garage (1972) with psychosexual elements of Roman Polanski's Repulsion (1965) and George A. Romero's Martin (1978) thrown in for good measure. Quite befittingly, the film opens with narration from a ambiguously Jewish psychoanalyst named Dr. Rosenberg (assumedly, of no relation to Alfred) who discusses the case study of an atypical 15 year old girl with latent lesbian tendencies who suffered from a series of erotically impassioned nightmares as a result of her overwhelming sexual repression. This psychosis-ridden girl named Odile (played by Jessica Franco Manera who is apparently Spanish slime-auteur Jess Franco’s real-life daughter) – a pixyish punk girl with a short semi-butch hairdo who sports booty shorts and Doc Martens boots – first enters the phantasmagoric dream realm of hot hallucinatory debauchery after having her first menstrual cycle while showering. Equally dismayed and intrigued by the heavy flow of hemoglobin seeping out of her pussy and dripping down her leg, Odile tastes her vital bodily fluids in a most prurient way. Odile must have some sort of unholy ancestral blood taint as it sends her on an often arousing yet harrowing nachtmahr by way of the dark underbelly of her subconscious, thus putting the little flapperesque lady in sexual contact with apparitions of luscious lesbian vampires, beauteous “Blood Countess” Elizabeth Báthory, and a stark-naked army of man-eating lesbos. Although Odile has a special appetite for kraut-cunts, she also encounters a variety of male perverts and unrepentant wienerschnitzel-fondling public-mastubators whom she has no qualms about sexually servicing, even if she does get involved with a little bit of castration and aggressive carpet-munching towards the conclusion of Mondo Weirdo. Despite the intrinsically hypnagogic nature of the film, all of the sex acts featured in Mondo Weirdo are graphic and real, including scenes of standard sexual intercourse, fellatio, female-on-female cunnilingus, borderline fisting, and homo sodomy.

Unlike like most pornography, Mondo Weirdo is keenly accentuated via an erogenous pulsating soundtrack by the Viennese EBM/industrial group Modell D’oo – who also composed the music for Carl Andersen’s previous facetiously titled work I Was A Teenage Zabbadoing And The Incredible Lusty Dust-Whip From Outer Space Conquers The Earth Versus The 3 Psychedelic Stooges Of Dr. Fun Helsing And Fighting Against Surf-Vampires And Sex-Nazis And Have Troubles With This Endless Titillation Title (1989) – henceforth making the film seem like an extended music video from sort of depraved bloodlusting S&M musical project. Undoubtedly, if Mondo Weirdo was a strictly silent film without a soundtrack it would lose 1/2 of its erotic potency and aesthetic essence as I cannot think of another better example of a musical score the fits the description of electronic body music as the film takes the human bod to bodacious and sometimes brutal extremes in a manner that is in unerring unison with its unruly yet startingly hypnotic sounds. In fact, the soundtrack is so gratifying and mischievously merry that I, too, felt like I was getting in on the action with little lass Odile and her many phantom lovers. Ultimately, the low-budget aura of Mondo Weirdo works to its advantage as a work with a very conscious punk rock aesthetic. Indeed, Mondo Weirdo is like an early Bruce La Bruce flick, except more appealing to breeders and lesbos than homos, although male-on-male copulation makes a brief yet savage appearance in the film. Although created a couple years after the artistic peak of the so-called Cinema of Transgression movement, Mondo Weirdo has more balls and succulent sadomasochistic sex appeal than anything ever directed by the likes of softcore pornographers Richard Kern and Nick Zedd and with the added bonus of not featuring the always detestable and ever so unattractive gutter-queen Lydia Lynch. Jessica Franco Manera may not be the most bewitching babe in the world, but she has a certain tragic cutesy-little-girl-who-has-fallen-from-grace quality that is altogether beguiling, as if she was the Louise Brooks of no-budget punk rock filmmaking. Even while inquisitively inspecting the freshly amputated cock of a maliciously mutilated man, Odile has a saccharine naivety that is wholly endearing.

After Odile accepts and acts upon her undying love of ladies, her erratic erotically-charged nightmares cease to appear and Mondo Weirdo concludes with the fitting end-title, “The End or a New Beginning.” Personally, I would have liked to see Odile hook up with some sort of Nazi chic Brando-type, but I guess Mondo Weirdo – a castration-anxiety-driven work of artsy fartsy punk pornography and pop psychology – is ultimately a male’s worst nightmare, even if an acutely orgiastic one. Like virtually all other works of its unclassifiable cinematic breed, Mondo Weirdo is as glaringly flawed work that looks like it was shot over the course of a single day, but that is also one of its greatest appeals. In short, Mondo Weirdo is the celluloid equivalent of a one-night stand with a mentally-imbalanced mixed-blood heiress-turned-hooker.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

June 11, 2012

3

comments

![]()

Sunday, June 10, 2012

Man, Woman and Beast

Man, Woman and Beast (1977) aka L'uomo la donna e la bestia aka Spell - Dolce mattatoio is most assuredly one of the most lavishly, methodically, and harmoniously crafted works of lecherous high-sleaze ever concocted. Directed by Alberto Cavallone of Blue Movie (1978) infamy, Man, Woman and Beast has all the aberrant auteur ingredients one would expect from the unabashedly debauched Italian filmmaker: killer sex (both literally and figuratively), sexually impotent artists, apprehensive commie verbal spew, and immoderately crude scatological fixations. Easily Cavallone’s most well-known and most artistically eclectic effort, Man, Woman and Beast manages to do the seemingly insurmountable by seamlessly hybridizing both the sensational surrealism and quasi-cinéma vérité realism that the filmmaker is celebrated for. Unlike the mental maestro’s subsequent effort Blue Movie – a work that was essentially assembled in an improvised manner on a nonexistent budget over the course of a week or so – Man, Woman and Beast has the certified picturesque stamp of an idiosyncratic 1970s masterpiece of Italian cinema, as it features obsessive direction and polished technique that is surely in recherché company with the 'self-indulgent' later works of Federico Fellini, yet it also includes incendiary libertine content that rivals that of Pier Paolo Pasolini’s Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom (1975), except executed in a charmingly campy fashion that is more akin to Dada than to de Sade. In fact, Man, Woman and Beast is a work that pays humble, if equally intimately perverse, homage to its aesthetic influences. Featuring appearances of artistic works by artists including Hans Bellmer, Salvador Dalí, Gustave Courbet, and José Posada, as well as thematic nods to literary lechers including Comte de Lautréamont, Jean Genet, Georges Bataille, and to a somewhat less noticeable and more anachronistic extent – Marquis de Sade – Man, Woman and Beast is a work that although culturally cultivated, does not attempt to mask it’s influences in a borderline plagiaristic fashion. Out of all its morally execrable influences, a delightfully deleterious tribute to Georges Bataille’s short novella Story of the Eye (1928) is ultimately the most assuredly memorable, negligently nefarious, and perversely potent. Despite its many scenes of somber and severe sadism, Man, Woman and Beast is indubitably a mischievously mirthful work that has few contemporaries in regards to its bodacious bestialized badinage and overall ribald absurdism. In short, Man, Woman and Beast is an ungodly and exceedingly audacious avant-garde work that pays paradisiacal homage to Dadaism like no other cinematic work before nor after it. In fact, Marcel Duchamp himself could not have done a more desirable job capturing the essence of the innately irrational art movement in celluloid form.

Upon superficial glance, Man, Woman and Beast seems like a domesticated Italian neo-neo-realist work due to its sometimes everyday portrayal of a seemingly traditional and typical Italian Catholic village, but underneath the thin veneer of normality lies a copious collection of vicious, violent, untamed, and even murderous sexual pathologies that would even astound the most seasoned of Reichian psychoanalysts and cannibalistic gay pornstars. In the village of wanton vulgarity featured in Man, Woman and Beast, a butcher packs his meat with his own unkosher meat, an Electra complex is utterly appeased via incestuous progeny-begetting familial relations, a lapsed-Marxist maniac attempts to tame his even more deranged wife, and a conspiring priest uses images of saints and the labor of unsuspecting children as a parasitic means to sell lottery tickets. Unsurprisingly, Man, Woman and Beast was filmed around the period of the so-called 'Anni di Piombo' (aka Leaden Years) during the mid-1970s in Italy when a nation-revamping revolution seemed like a very real possibility and when right-wing and left-wing were in unofficial camaraderie in their campaign to blow-up as many government buildings and officials as possible. Man, Woman and Beast does a most decorous job expressing this corrosive countrywide phenomenon at the community-level by the way of man’s most rudimentary, if base, form of social interaction: sexual intercourse. What becomes most apparent while watching the mostly sadistic sexcapades featured in Man, Woman, and Beast is that not one of the characters featured in the film approaches eroticism from a natural and utilitarian manner, hence the predominant theme of a society in disorder. In Man, Woman and Beast, sacrilegious sexual dysfunction and frivolous fetishism become sport and societal degeneration an uncontested, if unspoken and strategically veiled, matter-of-fact. Cavallone did a marvelous job highlighting this perturbing paradox by assembling a series of contradictory collages and montages comparing society of the old (outdoors and in public) and new (indoors and in privacy). For example, toward the end of Man, Woman and Beast, footage of jubilant villagers dancing jovially during an annual religious festival is spliced together with images of a young woman murdering her unsuspecting partner with scissors and scheiß during an impassioned session of sexual intercourse. Strangely (but most appropriately), the film ends with the melancholy face of an impressionable young lad who is undoubtedly symbolic of Italy's problematic future. It is not unlikely that this boy would grow up to be like Marco Corbelli; the lurid cross-dressing lunatic behind the Italian noise project Atrax Morgue who committed suicide by the way of hanging in 2007 after a lifetime of necrosis fetishism.

Director Alberto Cavallone once admitted that the character of a Christ-like homeless man featured in Man, Woman and Beast was his alter-ego. Fittingly, this mystery man is a herald of change, but – unfortunately for the villagers and himself – their damned futures are already foretold. The uncanny wanderer also meets a deplorable doom that would anticipate the thoroughly demented defecation-phile anti-hero of Cavallone’s successive film Blue Movie. Indeed, in the wretched realm of Man, Woman and Beast, god has died a most unflattering death and has gone to waste in literal human waste. Even the fanatical godless commie of the film has lost his faith in Marxist propaganda and the world revolution, as expressed by him vocally and when he superimposes an image of Vladimir Lenin over a picture of a woman’s sin flower, which is most certainly a bantam and frolicsome expression of Cavallone’s own newfound political disillusionment. Unquestionably, Man, Woman and Beast is an uncompromising expression of nihilism and a bold testament to the apocalyptic arrival of der letzte Mensch, but also a work of active artistic nihilism that had the potential to spark a revolution in cinema that was only vaguely hinted at by future subversive arthouse filmmakers like Jörg Buttgereit, Karim Hussain, and Andrey Iskanov. Disenchanted with commercial success and (arguably) cinematic artistry in general, Cavallone would later get give total way to his abased aesthetic proclivities as expressed by the hardcore pornographic nature of most of his later works. Aside from possibly his lost masterpiece Maldoror (1977), Men, Woman and Beast is unmistakably Cavallone’s crowning achievement as a filmmaker and his celluloid magna opera. Like his vital influence Georges Bataille, Cavallone is one of few artists that successfully proved that artistically-refined works can be pornographic and vice versa. If it were not for his later propensity for creating mostly incoherent esoteric hardcore pornography, Cavallone may have gone onto consummate a reputation as grand and venerated as fellow Italian filmmakers Federico Fellini and Pier Paolo Pasolini, as he certainly deserves it, even if only for Man, Woman and Beast; a blissfully carnal phantasmagorical work that does the seemingly inconceivable by vigorously raping the senses in a spellbinding and inordinately multi-orgasmic way with salacious sin-ridden scenes of grotesque human depravity. As Nietzsche's Zarathustra once preached, "as for me, I rejoice in great sin as in my great solace."

-Ty E

By

soil

at

June 10, 2012

2

comments

![]()

Tuesday, June 5, 2012

The Raid: Redemption

Quite assuredly, red-band clips or trailers from most necessarily violent action films are always followed with a rush of excitement for said title. This method of delivery involves making an almost whispered promise of at least one especially outstanding scene, the one in which is in question as the video streams or graces the cinema screen. It would be quite the disappointment if that preemptive, in this case, single scene was the only of its kind in quality, whether it be in suspense, bloodshed, or gratuitous feral generosity. It would be of similar character to show the final fight of Flash Point or even The Man from Nowhere, to a pair of virgin eyes for the sake of absorbing salivation for your own esteem's gain, which, admittedly, I am guilty of. Thus was the curse I carried for months after watching a red-band clip from The Raid: Redemption. I feared an all-too real terror of this scene spoiling a key moment that I had built myself up for, so you can imagine the feeling of dread when, during my temporary stay at the cinema while viewing The Raid: Redemption, this scene in particular popped up. But alas, the scene continued without a hitch or hiccup! Gareth Evan's masterful global marketing team knew and approached the limitations of exposure with a certain bravado lost upon most action films and their combined run at arousing attention. It was as if a heavy burden was lifted off of my shoulders and I could open up to The Raid: Redemption. I could let it tell me, without hesitation, all of its little secrets and worry me with all of its woe. You see, for me and most everyone I know who has bore witness to its third world grandeur, The Raid: Redemption marks the graduation of this new blend of international action film. One in which encroaches upon the formula of simple and similarly structured action pieces such as Ong-Bak or The Protector, save for the sparsely seen Indonesian fighting style of Pencak Silat. The two aforementioned Tony Jaa vehicles were met with massive appraise but were also maligned for their doe-eyed absence of thought, whereas The Raid: Redemption wrestles from this stranglehold with a candle of ease that holds steadfast without a flicker or chance of dimming.

It's become so that I find it difficult to sit and review, in-thought, a post-Raid: Redemption-esque film without finding myself victim of that classic compare/contrast to the next best thing, which is obviously being The Raid. For in its wake, left screaming an army of "boorish males", comes an expectation that might be nigh to match - an obsessive exercise in ceaseless savagery, each minute being more daring than the last and each fight sequence becoming more stylized, choreographed, and calculated. Since the shriek of this Indo-wizardry was heard worldwide, you can be certain that these highly-marketable future Eastern exercises of sweat-soaked exertion won't end with The Raid: Redemption and for that matter, any of its sequels. Many attempts will be made upon their title of champion and these challengers' motives will fall victim to cynical ratings as cinephiles use the schematics of The Raid: Redemption as an impromptu gradebook, cursing while X-ing in heavy red permanent ink, not even bothering to wonder where, or why, it all went so wrong for them. These "substitutes" will only increase in numbers while the action film of our heritages fate relies on the likes of A Good Day to Die Hard and The Expendables and their promised sequels (or should I say squeals, drastic to stay afloat these are, with mild results). The problem falls on Hollywood and their hasty decisions to brand Western audiences as ignorant to the beauty and eccentricity found in foreign styles of fighting. Hollywood will continue to pump out action remakes of popular foreign films with a soulless nod to an alien and titular fighting style. Their repayment plan? To replace a key diversified system of offense with sub-advanced grappling maneuvers merged with hyper-edited body blows. You might as well refer to the Bourne handbook for how I imagine The Raid remake turning out, but I digress. Known in its homeland as Serbuan Maut and then internationally as The Raid, the evolution of title didn't quite stop there. Overseas in the American market, The Raid later had "Redemption" tacked on to its title to allow copyright to resume naturally as well as opening up options for a sequel, or in this case, two. Released at Sundance with an alternate score from Mike Shinoda of Linkin Park "fame" and the unfortunately named Joseph Trapanese, this exclusive composition for The Raid served as an occasionally unruly love letter to a film that needed no such grabs for attention, especially from a post-applied promise of being faithful to the images.

Unfortunately, the faithfulness to the original artistic vision wasn't all in check, as the Western theatrical run felt the need to doll itself up beyond the limitations of an American adrenal-pop soundtrack considering intelligence. Things proved all and good until the simplicity of the electronic score, that followed alongside with the hurried sense of survival, ran out and gave room to the scene-chewing appetite of a mid-chaos dubstep routine which, far dependent on your opinion of the (awful) genre, is most unfitting for a frenetic cinematic scenario, especially if it wants to be taken seriously. But in regards to the U.S. release of The Raid: Redemption, this was close to its only sin. The Raid: Redemption, if to be remembered by a single act, had one thing going for it and that is apart from the luxurious and fruitful sequences of violence, aways from the viciousness of tenant to tenant, and far from the incredible death scenes that will leave your nails clawing at plush. No, what The Raid: Redemption has is an incredible sense of utter helplessness and defeat, a feeling that could not be anticipated from watching the trailer alone. Now, mind you, a trailer that boasted the tagline of "20 Elite Cops - 30 Floors of Hell" refused to give way to the actual gravity of the situation which is a merit to be thankful of. Imagine my surprise when this micro-army of skilled officers were scattered, slaughtered, and slain. The Raid: Redemption, no matter what you may read from genre-waving bannermen, applies well within me as the cinematic equivalent of an old classic arcade-style beat em' up - in particular, Streets of Rage (although a rendition that meets the concrete isolation of Die Hard). You have for potential evidence a small band of aggressive law-abiding citizens battling wave after wave of weapon-wielding rapists, junkies, murderers, and other related fallen ilk. Each character combats his own specific mini-boss, of sorts. The floors of the building can be taken, literally, as levels, and as an added bonus you are also given the architectural despondency of the Silent Hill multiverse. It is no coincidence that the core demographic suited for The Raid: Redemption are 18-32 year old fans (gender not applied as my fiancée was quoted as dubbing the film "a masterpiece") of ferocious competition. Much to their surprise too, is that it is gift-wrapped in a package anonymously sent to "Fanboy". No return address either, hmm.

If you have it within you to embrace such nonchalant acts of treachery, murder, and extreme violence then open your ears, eyes, arms, and tendons to this assault on the senses. The Raid: Redemption can easily be followed and the events can even transpire/unfold to the dull senses of a quasi-intellectual cinema-goer. The Raid is that certain sort of film that you can view once and rely on later as a perfectly competent sound and space filler as you multitask on whatever in-house errand(s) lie on your plate, and in which by some magical method of multimedia memory, The Raid: Redemption can be mentally visualized as well as synchronized alongside the groans and moans of both pools of victims - good and bad. For exceptional physical feats, look no further. You will notice the actions of those depicted on-screen, no matter the side you choose, attempt to disguise themselves as falling under their own category of exceptional heroism but that is never the case in The Raid. Even the rookie SWAT lead, Rama, has an agenda for entering the building and only when their original plan becomes so, for lack of a better word, fucked, does he step up to the plate to ensure the safety of himself and the scattered survivors. Welsh born director Gareth Evans would obviously follow up the enormous critical success of The Raid so in his future we can assuredly see two more sequels to the Indonesian debut and as I mentioned before, at least one American remake. When asked about his plans for The Raid: Redemption's sequel, now tagged with the subtitle ": Retaliation", Evans could only comment about his hopeful inclusion of car chases - "I want to bring car chase elements to it as well. So we have like a cool fight scene where you go inside a car, fighting against four people as it’s speeding along a one-way." Now, I'm all for diversity but the greatest appeal of The Raid was its horrific seclusion - a terrible event sealed off from outside communications or contact. If these men are even remotely allocated to another life-or-death situation, then what is keeping them from turning the wheel. I'm not sure how it could possibly work out without some method of escape but my brows stay curiously and cautiously raised. This beast was meant to be leashed. If you slaver for intense bodily nihilism then look no further. The Raid: Redemption reigns king of overkill - a rare film event in which officers of the law die like dogs while the villains perish under much more honorable circumstances, and that is more bravery than I ever could have expected from such a piece.

-mAQ

By

soil

at

June 05, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Monday, June 4, 2012

Le nécrophile

Unfortunately, temerarious and innovative films about necrophilia are quite hard to come by, so I am always stimulated by the possibility of viewing a new work of audacious avant-garde corpse-fucking. With their wealth of films relating to jaded incestuous romances gone awry and sexually aberrant behavior galore, one would think that France would have produced a number of revolutionary man-loves-corpse epics by now, but quite regrettably, that is not the case. Naturally, when I discovered the 36-minute French short Le nécrophile (2004) directed by Philippe Barassat, I was on tenterhooks. Admittedly, as a longtime kraut-lover and loather of abstract ideas relating to culture-distorting liberty, I must admit that I am an unrepentant Francophobe of sorts who would rather watch a screening of Schindler’s List at an Israeli drive-in than languish through the mundane masturbatory marxist disgorge that comes along with a Jean-Luc Godard marathon. That being said, I did not expect Le nécrophile to be as romantic nor as aesthetically-gratifying as either of Buttgereit’s Nekromantik flicks, yet it certainly proved to be a more farcical work with its brief yet fulfilling buffet of jovial incestuous pedophilia, campy cannibalism, and marvelously morbid moments of exceedingly awkward necrophilia. Indeed, Le nécrophile may deal with some of the most taboo topics ever explored in cinema, but these sordid scenarios are expressed in such a merry and startlingly palatable manner that I almost forgot that I was watching a film about serial necrophilia and the long-term effects such demented behavior could potentially have on a seemingly virginal preteen girl. The film follows a loathsome lunatic who is so grotesque and patently pathetic in appearance (and character) that he looks like the ill-fated bastard spawn of Peter Lorre à la Fritz Lang’s M (1931) and a mutant frog (He even has an elastic bug-catching tongue to boot) with Down syndrome. When not isolating himself from the general peasant populous of the decrepit urban ghetto he calls home, the nervous necro basks in bumping angelic cadavers in the night. This unintentionally humorous heteroclite fellow is so terribly timid that he is even unstrung whilst in the one-sided company of an inanimate corpse. When the piteous man is forced to adopt his young niece after her parents die, he must become more creative and covert in regards to probing cold-cadavers during the dead of night. When an adolescent Afro-Arab teenager falls in crossbreed puppy-love with his niece, the neurotic necro finds that his much cherished midnights of intimate necromancy are disastrously jeopardized, thus eventually culminating into dreadfully flustering results.

What makes Le nécrophile especially deathly dreary and markedly morose is not the actual moments of debauched necrophilia, but the domestic dystopian setting of the film; a discernibly decayed French ghetto inhabited by third world refugees and thoroughly mongrelized post-racial Frenchmen. While the unusually unprepossessing anti-hero resembles a bloated corpse himself and is thus symbolic of France of the old (one could argue that the corpse-fucking is an allegory for the inability of the average working-class Frenchman to respond to change) and now degenerated, the lovesick brown boy is denotative of the new 'French'; an innately hostile alien population that will ultimately replace the indigenous race(s) of France via mass illegal immigration and miscegenation. Out of all the characters featured in Le nécrophile, the necro’s niece is indubitably the most seemingly pure and untainted. With her glistening golden blonde-locks and angelic fair-skin, one ultimately feels more repelled by the prospect of the colored teen defiling her than seeing the depraved necrophile manhandle an expired corpse. As one soon finds out while watching Le nécrophile, the nymphet niece is not exactly the most unsullied and immaculate of little girls, but she is a self-sacrificing mademoiselle who will do anything – and I mean anything – to safeguard her exceedingly eccentric uncle and the dubious relationship that they share, even if it involves being deflowered at a less than mature age in a most nauseous and nefarious sort of way. In the end, the little gal proves to be her Uncle’s most dutiful guardian angel, despite the fact that she seems to be at an already more corrupted and unsalvageable state than a man that delights in dating and devouring the deceased. Although tragically despoiled during her early years of childhood, the bittersweet little lass is quite stalwart, stoic, and sophisticated for her age due to a short lifetime's worth of personal struggle, thus she acts as a symbol of hope for France; a once proud and invigorative nation that is now literally full of corpses (who actually make a reanimated appearance in the film) from great heroes of a long forgotten past.

Although featuring some of the most unmentionable moments ever captured on celluloid, Le nécrophile is essentially a lovesome (if ludicrous) and sentimental (without being simpleminded) tragicomedic neo-fairytale about the unbreakable bond of family ties. If the longtime decadent and irrevocably deracinated French have to make a film about necrophilia, incest, and cannibalism as a way to inspire ideas of self-preservation, nationalism, in-group loyalty, then so be it. I, for one, always wished Georges Bataille was a fascist and Philippe Barassat's Le nécrophile seems to be an undaunted expression of the next best thing.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

June 04, 2012

0

comments

![]()

Friday, June 1, 2012

The Hunger

Admittedly, old school Deathrock aka Gothic rock has always been one of my favorite subgenres of music, so it should come as no surprise that I have made a point to watch Tony Scott’s debut-feature film The Hunger (1983) – one of few mainstream works to pay tribute to the often mocked but rarely seriously examined music movement – a number of times over the years. In the film, blood takes on a orgasmic ejaculatory quality that for vampires is an afflicting addiction that comes with a viciously vexatious withdraw if an undead addict fails to adequately indulge in these vital living fluids. Opening with the song “Bela Lugosi’s Dead” – which is often regarded as the first Gothic rock single ever released – by British Deathrock group Bauhaus, as well as iconic footage of the band (mainly singer Peter Murphy) itself, The Hunger is an extravagantly stylized, erotic phantasmal work that pays more than apropos tribute to a music subgenre that is often maliciously maligned (if sometimes deservedly so) and endlessly ridiculed, but rarely objectively diagnosed for its actual aesthetic attributes and influence. Fittingly, proto-Goth David Bowie plays a starring (but progressively relinquishing) vampire role in The Hunger, as does French actress Catherine Deneuve; the ridiculously resplendent international film goddess that starred in Roman Polanski’s early dark masterpiece Repulsion (1965) and Luis Buñuel’s popular work Belle de Jour (1967). Susan Sarandon also co-stars in The Hunger as the lesbian love interest/prey of Deneuve's character. Of all the filmmakers that could have been chosen to direct a modern Deathrock-inspired vampire flick, I would have least expected Tony Scott – a filmmaker best known for vapid blockbuster films like Top Gun (1986) and Man on Fire (2004) – but then again, the Hollywood auteur got his start creating successful television commercial advertisements, thus making him quite germane for directing the radiantly stylized montages and overly expressive horror/erotic interludes featured throughout The Hunger; a chimerical shadow play shot on celluloid. In fact, Scott cites the feverishly decadent and schizophrenically-structured work Performance (1970) directed by Donald Cammell and Nicholas Roeg and starring Bowie's one-time boy-toy Mick Jagger as one of the greatest influences behind The Hunger. Breaking with convention and expectations in almost every regard, The Hunger is a vampire lesbo flick on a gloriously grotesque cocktail of LSD and steroids that borrows liberally from every subversive bloodsucking flick of the past, including F.W. Murnau’s Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror (1922) and Hammer Horror classics like The Vampire Lovers (1970) and Twins of Evil (1971). Watch out delusional Afrocentrists, The Hunger features an ancient Egyptian vampiress of Indo-European stock whose glaring lack of melanin could be only that of an agathokakological undead honky. I do not think it would be a stretch to speculate that pseudo-sinister sodomite Aleister Crowley’s ultra-hedonistic quasi-religion Thelema – which adopted a triad of deities from ancient Egyptian religion – also influenced the audacious aura, libertine themes, and Kenneth Anger-esque music video mysticism of The Hunger.

Indubitably, I think The Hunger would have somewhat benefited from having been set in New York City or Los Angeles, California as opposed to London, England. In fact, Tony Scott wanted to shoot the entire film in NYC, but due to monetary constraints, the English filmmaker settled for the dreary urban streets of his own homeland. As someone who has always had a greater affinity for American west coast Deathrock groups like Christian Death, T.S.O.L, and 45 Grave over Goth groups from over the pond, I feel that The Hunger could have had a more ‘magickal’ cosmopolitan feel of wandering-endlessly-through-undying-eternity had it been set in relatively rootless, amoral, and ahistorical Southern California. Despite having to compromise in regard to location setting, The Hunger still often has an anomalistic essence that tends to transcend national boundary. In fact, Tony Scott regards the closing shot of London in the film as geographically ambiguous, as if the film could have taken place in any modern metropolis. The personal home of the lead vampire lovers Miriam Blaylock (Catherine Deneuve) and John (David Bowie) has a culturally-refined aristocratic quality that is decidedly timeless, yet at the same time startlingly futuristic. Tony Scott also made congenial use of artistically eclectic Art Deco architecture around London to further compliment the delectable yet decadent atmosphere of The Hunger; an unwonted vampire flick that, unlike Bowie's character in the film, has scarcely shown its age over the years. Upon its original release, The Hunger was critically lambasted by the majority of film critics, including the always pompous and never less-than-charming Roger Ebert who described the film as, "an agonizingly bad vampire movie." David Bowie himself even had doubts about the film stating, "I must say, there's nothing that looks like it on the market. But I'm a bit worried that it's just perversely bloody at some points." As the test of time has undeniably proven, the popularity of The Hunger has only steadily risen over the years, not least due to the film being one of the most scrupulously polished and ideally idiosyncratic vampire lesbo flicks ever made, but it also very possibly the greatest and most cultivated abstract filmic expressions of the Deathrock movement. Unless Miloš Forman, Oliver Stone, or Gus Van Sant decides that a lavishly-produced Rozz Williams biopic will be their most ambitious attempt at directing a celluloid opus magnum, I ingenuously doubt that the world will see a more vitalizing dark love letter to the long spiritless Deathrock movement than The Hunger.

Quite honestly, the first time I viewed The Hunger about a decade ago or so, I felt the work was ridden with pulsating pomposity and unrealized artistic pretensions, but the film has certainly grown on me over the years, so much so, that I always look forward to re-watching it and discovering elements of the film that I had yet to notice before, sort of like with Tony's brother Ridley's masterpiece Blade Runner (1982). Indeed, in terms of aesthetic overload and plot incoherence, The Hunger, especially for a mainstream vampire film, is exceedingly self-indulgent, but so are a vast percentage of the most illustrious films ever made. Aside from True Romance (1993), The Hunger is the only Tony Scott film that I can wholeheartedly recommend, which makes it all the more interesting when one considers that it was the mostly hackish filmmaker's first-feature. Devastated by the harsh reviews that The Hunger received upon its initial release, one can only wonder whether or not Scott’s career as a filmmaker would have went a different, more artistically-ambitious route had the vaulting vamp flick received the mostly positive praise it deserved. Although Scott concluded The Hunger on an amibigous note hinting at a potential sequel, such a project would not even begin see the light of day, although the film would inspire a mediocre softcore TV horror anthology of the same name also starring David Bowie (at least for the second season). In 2009, Warner Bros. announced that the world would soon see an unnecessary remake of The Hunger based on a screenplay written by Whitley Strieber; the horror author whose novel the original film was based on. Although I find the idea of a remake to be dubious and – at best – monetarily-inspired, it would be interesting if Tony Scott followed in the footsteps of Alfred Hitchcock and re-made his own film, especially after almost three decades of overwhelming mediocrity and mundanity as a filmmaker.

Like Lemora: A Child's Tale of the Supernatural (1973), The Hunger is one of the oh-so unsurprisingly few lesbian vampiress flicks that rises above being aesthetically-pleasing smut and for that alone, it is a noble cinematic triumph worthy of postmortem eulogy. Although most of Tony Scott's films epitomize everything that is deplorable, soulless,and humdrum about Hollywood, at least he directed what is very possibly one of the most transcendent vampire flicks of the 1980s, as well as one of the most high-class and hunky-dory vampire films ever made.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

June 01, 2012

5

comments

![]()

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.