While I spent almost a decade fucking up public property with my skateboard, own a surfer style longboard that I mess around with sometimes, and have lived at the beach for a good portion of my life, for some reason I never got around to learning how to surf and after watching the obscenely underrated cult item Big Wednesday (1978) directed by proud right-wing Hebrew John Milius (Dillinger, Red Dawn), I now realize that it is one of the single greatest regrets of my life. Indeed, after recently getting around to watching the film for the first time this month, I can say without exaggeration that it is probably one of the most, if not the most, underrated and obscenely overlooked films of the New Hollywood era, but of course it was probably considered to be too ‘reactionary’ for people at that time of it initial release since it portrays hippies as gleeful drug-addled automatons, features an extremely likeable and sympathetic all-blond Aryan cast, was inspired by ancient Greek and Norse mythology, does not feature any gratuitous sex scenes, and does not attempt to make any sort of heavy-handed leftist political statements about the Vietnam War (which Milius notably attempted to fight in, but was denied entry into the Marine Corps due to having chronic asthma). Originally expected to be a huge box office hit by a number of Milius’ filmmaker friends at the time, including a fairly young Steven Spielberg, who somewhat absurdly described it as, “AMERICAN GRAFFITI meets JAWS,” the film was a huge flop and was ruthlessly trashed by all the predictable mainstream leftwing film critics, who probably had a hard time sympathizing with a bodacious brigade of shamelessly masculine happy-go-luck blond beast beach rebels that makeup what is undoubtedly a modern-day West Coast Männerbünde.

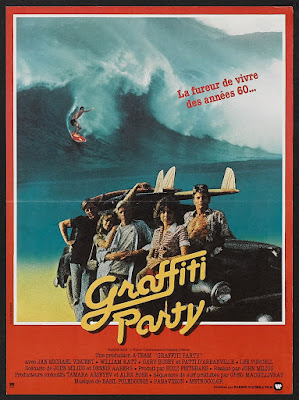

Admittedly, Milius’ film is somewhat like a sort of surfer equivalent to American Graffiti (1973), albeit a whole lot less lame and more subversive in terms of spirit. Directed by a rightwing Jew who has proudly described himself as “Zen Fascist” and, according to Arnold Schwarzenegger’s autobiography, once declared “There is only one Nazi on this team. And that is me. I am the Nazi,” when Italian producer Dino De Laurentiis bitched that he did not want to cast the Austrian actor as the eponymous lead Conan the Barbarian (1982) because he thought he was a “Nazi,” Big Wednesday is a fairly simple yet highly rewarding coming-of-age film with unwavering testicular fortitude that reveals in a somewhat melodramatic way the fairly pathetic fact that some peoples’ lives reach their peak when they are only in their late-teens and early-twenties. Set over a twelve year period beginning during the summer of 1962 and concluding during the ‘Great Swell of '74’ when the protagonists give their swansong to surfing during an eponymous day when the waves reach upwards of 20 feet, the film is undoubtedly Milius’ closest thing to an auteur piece as a work that was largely based on his and his co-writer Dennis Aaberg’s personal experiences as Malibu surfers. Seamlessly adding Arthurian overtones to largely autobiographical anecdotes, Milius’ rather entrancing cult flick features a hero’s journey with a sort of Nietzschean theme about the ‘Eternal Return’ and the cyclical (as opposed to linear) nature of history and how each generation produces a group of sort of surfer aristocrats and bluebloods of the beach that act as influential surfer gods to the younger generation, who ultimately replace them with their own surfer royalty when it is their turn to rule the beach. Of course, as the film somewhat sentimentally demonstrates, the best thing a man can hope for is to leave a legacy. Indeed, the lead protagonist might be a dipsomaniacal lumpenprole that makes his living cleaning the pools of anally retentive people that probably think he is poor white trash, but among surfers he is a legend whose legacy simply speaks for itself.

While Milius—a mensch that hardly looks like he could have ever made for an apt model for an Arno Breker statue—has described his reasoning for casting tall, muscular, and blond actors as being because he wanted the protagonist to look traditionally “heroic,” there is good historical reasoning for having men of such an overtly Aryan physique as the leads, as they are symbolic of Southern California’s German Wandervogel and Naturmensch roots and the fact that Germans immigrants would ultimately play a crucial cultural influence on both the surfer and bohemian/hippie way of life. Indeed, 60 years before long-haired blond surfer dudes and their equally unclad lady friends where living a radical communal way of life on the beaches of Southern California during the late-1960s and early-1970s, Teutonic novelist Hermann Hesse (Siddhartha, Steppenwolf), whose literary works would ultimately have a huge influence on the counterculture movement, met four longhaired sandal-sporting Wandervogel members in 1907 who took him to their commune in Ascona, Switzerland where he received a natural cure for his debilitating alcoholism. Naturally, I bring up Hesse to illustrate the deep roots of the Wandervogel movement and how is went on to influence many individuals and subcultures that have never even heard of it. The Wandervogel movement would also influence the proto-hippie Nature Boys of California, who were largely German immigrants and were promoting a life of veganism, nudism, and beards and long-hair during the 1910s. Of course, the Völkisch artwork of Fidus (aka Hugo Reinhold Karl Johann Höppener)—a Wandervogel member who lived in a proto-hippie commune and who once served a prison sentence for public nudity (in fact, his mentor, German Symbolist painter Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach, bequeathed him with the name “Fidus” aka “faithful” after he served said prison sentence)—would ultimately inspire the psychedelic aesthetic of both surfer and counterculture art during the 1960s.

As a coming-of-age flick that depicts a group of young surfer friends who ultimately begin succumbing to more hedonistic vices, Big Wednesday depicts what is arguably the last ‘innocent’ generation of surfers before the age of criminally-inclined rock star surfers like Bunker Spreckels and Rick Rasmussen, who both joined the surfer division of the 27 Club and died particularly pathetic deaths before they even reached their thirties. Notably, Spreckels (real name Adolph Bernard Spreckels III), who was a German-American that claimed to “come from a Viking line of Teutons” via his paternal line (he was the great-grandson of German-born sugar baron Claus Spreckels), was the stepson of Clark Gable and experimental filmmaker Kenneth Anger would pay tribute to his legendary Luciferian spirit and Aryan handsomeness with the 4-minute short My Surfing Lucifer (2007). While Big Wednesday depicts a group of young surfers that were from the generation before heroin and shitty rock music began plaguing surfer greats like Spreckels and Rasmussen (who were both involving in drug dealing), it is clear that these characters, who are perfectly played by leads Jan-Michael Vincent, William Katt, and Gary Busey, have the same sort of innately rebellious spirit, as sort of modern-day Norse Berserkers that are prone to trance-like fits of fury while both on and off their surfboards. Making up a sort of unconscious Malibu Männerbünde as an eccentric collective of inordinately loyal surfer comrades with their own set of rules, rituals, routines, and even lingo, the sunbaked beach boys of the film reveal that, although surfing is a fairly individualistic activity that is in stark contrast to popular collectivist-minded team sports like baseball and football, personal relationships are certainly one of the most important and memorable aspects of the lifestyle. Indeed, as an ex-skater, I can certainly say that I have more fond memories of the many people that I skated than the best tricks I ever landed. Somewhat unfortunately, I can also attest that, not unlike the surfers in Milius’ films, some of the greatest skaters that I was friends with also become some of the biggest fuck-ups and degenerates when they reached their late teen and adult years, but I guess that is what one should expect from individuals derive fun from intentionally putting themselves in various dangerous life-or-death situations.

Next to his buddy Paul Schrader, there has probably never been another screenwriter who went on to have such a successful career as a filmmaker as John Milius, who most notably penned the best lines of dialogue from Dirty Harry (1971) and its first sequel Magnum Force (1973) and received an Academy Award nomination for his screenplay for Apocalypse Now (1979). Originally written by Milius in 1969 under the somewhat less tempting title The Psychedelic Soldier (he was later inspired to change the title to its current name to mock a popular hippie button of the late-1960s that read “Nirvana Now”), Milius is the man responsible for the most memorable lines of Apocalypse Now, including “Charlie don't surf!” and “I love the smell of napalm in the morning.” Needless to say, watching Big Wednesday sometimes feels like the cinematic equivalent of hanging out with the friends of Apocalypse Now character Lance B. Johnson, who notably rides some waves after his new pal Lieutenant Colonel Bill Kilgore covers him from enemy bullets by having helicopters drop napalm on a surrounding gook village. Of course, the films also deals with the issues of the Vietnam War and how one of the surfers dies in battle, but it never resorts to petty political sloganeering, emotionally manipulative sermonizing, or pathetic melodramatics, as the characters deal with war as if it is a normal fact of life. Featuring special water cinematography by innovating surfer George Greenough, who also did camera work for Bruce Brown’s classic surf doc The Endless Summer (1966) and Peter Weir’s early masterful metaphysical mystery The Last Wave (1977), Big Wednesday is certainly as technically accurate and innovative as fictional surf movies come, yet you do not have to give a shit about epic 20-foot waves to enjoy it.

Sentimentally narrated by lovably ugly Aryan actor Robert ‘Freddy Krueger’ Englund at the beginning of each of the film’s four main chapters, Big Wednesday begins with a segment entitled “THE SOUTH SWELL – Summer 1962” where the viewer is introduced to the main three protagonist, or as the rather nostalgic unseen narrator states, “I remember the three friends best: Matt, Jack, Leroy. It was their time. They were the big names then. The kings. Our own royalty. It was really their place…and their story.” Although a seeming loser in just about every other aspect of his life, Matt Johnson (Jan-Michael Vincent in a most fitting and perfectly played role)—a character inspired by a real-life surfer named Lance Carson who suffered from alcoholism for most of his life and who was inducted into the International Surfing Hall of Fame in 1991—is the greatest surfer in town and the uncontested ‘king’ of his beach, ‘The Point.’ As an anally retentive yet inordinately mature and stoic chap, Jack Barlowe is certainly Matt’s total opposite, yet they are still best friends and the best surfers in town. Although not nearly as pathetically self-destructive as the lead protagonist, Oklahoma-born beach hillbilly Leroy ‘The Masochist’ Smith (Gary Busey) is easily the most unhinged yet simultaneously most jovial of the trio and he wastes no time in hassling a couple young surfers for a board at the beginning of the film after a quite hungover Matt misplaces his own. As Leroy's playfully authoritarian behavior demonstrates, the beach has its own set of unofficial rules and those individuals (e. g. ‘Hodads’) that do not follow them must pay the price. At the entrance of the Point is a sort of Lovecraftian gate in ruins that hints that a great civilization once thrived there, but now blond beast barbarism rules the beach and Matt, Jack, and Leroy rule by example with their oftentimes ethereal and entrancing wave-riding. In fact, Matt is such a legendary figure among young Malibu surfers that they can only seem to recognize him when he is actually surfing, as if he is too meek and pathetic looking to impress anyone otherwise. Unfortunately for the trio and their equally blond friends, they are at a point in their lives when their carefree existences are about to be threatened and they soon must come to accept that not everything in life is fun and games, even if you happen to be one of the greatest and most radical surfers of your generation.

If the protagonists of the film have any sort of all-wise father figure and mentor, it is a burly bearded beach bum named ‘Bear’ (Sam Melville), who is a Korean War veteran that seems to have no life of his own and instead lives vicariously through Matt and his friends. When Matt and his friends have parties, Bear also symbolically hangs outside the entire time, as if he knows he is too old to be truly a part of the group and thus always stays slightly off to the side. Bear’s greatest claim to fame is that he used to regularly surf crazy waves in Hawaii and, as he states like an old wise man recalling his experiences, “Once I rode it alone in Point Surf at Mākaha at 20 feet.” As a sort of compulsively cerebral yet carefree surfer priest/philosopher/poet who only gets pissed when someone or something impedes on his surfer lifestyle, Bear stoically declares to some young kids in regard to the innately individualistic nature of surfing, “You’re always alone, anyway. That’s the test of a surfer to ride alone. You shouldn’t have to depend on anybody but yourself.” As his words and actions reveal, Bear considers himself a sort of perennial surfer, even if he is never depicted riding a board once in the entire film. Bear does not believe that the leads have truly lived up to their full potential yet and as he tells the kids while working on a longboard in regard to Matt and his friends’ ultimate Arthurian mission, “It’ll be a swell so big and strong it will wipe everything that went before it. That’s when this board will be ridden. And that’s when Matt, Jack and Leroy…they could distinguish themselves. That’s the day they can draw the line.” Of course, the longboard is symbolic of Excalibur and, not unlike like King Arthur with the legendary magical sword in the stone, Matt is the only one that will be able to use it, but only on the right day at the right time when god has blessed him with the appropriate waves that will challenge both his courage and talent. Naturally, both Jack and Leroy will join him in surfing these waves on the eponymous big day, but it is ultimately alpha-surfer Matt that will reach the deepest and fullest form of transcendence, as he is the greatest hero of his generation.

While Leroy pretty much seems to be willing to fuck anything that moves so long as it has a warm wet hole and thus does not seem like the sort of fellow that could settle down and share his life with a woman for any notable period of time, both Matt and Jack soon acquire girlfriends. Indeed, while Matt hooks up with a supposedly lecherous female surfer and tomboy named Peggy Gordon (Lee Purcell) who is just as tough as the boys and who will ultimately act as the lead protagonist’s much needed backbone, Jack hooks up with a cutesy Chicago-bred diner waitress that just moved to the area named Sally (Patti D'Arbanville), who states to her new beau in regard to the stark contrast between sunny Southern California and her ex-hometown, “It’s really different here. Well…back home, being young was…just something you do until you grow up. And, well, here…here it’s everything!” While everything seems to be going great for the protagonists after they have a party at Jack’s mother’s house where they beat up a gang of proudly arrogant party-crashers from Burbank, reality smacks them in the face when they decide to travel south of the border to Mexico to engage in mindless hedonistic activities and ultimately realize that they are not as tough or brave as they thought when they are out of their element and left vulnerable to the unpredictable hostilities of the rather unforgiving third world. Indeed, aside from Peggy revealing to Matt that she is pregnant and plans to keep the baby while she is absurdly chugging down a can of cheap Mexican beer (!), the boys get in an ugly bar fight involving knives and bullets, not to mention the fact that Jack’s prized car is practically left totaled. Not surprisingly, self-described masochist Leroy is the only one that enjoys the trip and he even impulsively marries a teenage Mexican girl, though he ultimately leaves her behind.

As the narrator states at the beginning of the second chapter entitled “THE WEST SWELL – fall 1965” in regard to the decidedly dispiriting spirit of time, “The summers passed with each year. I don’t seem to remember them anymore. I remember the fall and the coming of winter. The water got cold. It was a time of the west swell. A swell of change. A swell you usually rode alone.” Always the mature and disciplined friend in the group, Jack annoys him comrades by joining the enemy and becoming a lifeguard at their surf spot. In fact, while at work, Jack even unwitting yells at Matt for sleeping on the beach after assuming he is just some random drunken wino. Of course, Matt is indeed drunk and Jack is forced to punch him in the face and banish him from the beach that he was once the king of after he causes a car crash while playing around in the street and pretending to be a matador that dodges cars instead of bulls. To make matters worse, all the boys have received draft notices for the Vietnam War, hence Matt's perpetuation state of inebriation. Somewhat ironically, while his protégés have more or less hit rock bottom and no longer speak to one another, Bear has become a successful surf store owner with his own surfboard brand and he is getting ready to get married, so naturally he becomes quite disheartened when Matt randomly shows up at his shop and pathetically declares that he no longer wants to be a surf hero, complaining like a true loser, “I don’t want to be a star. My picture in magazines, having kids look up to me. I’m a drunk, Bear. A screwup. I just surf because it’s good to go out and ride with friends. I don’t even have that anymore.” Of course, big burly Bear refuses to listen to such pathetic crybaby talk and sternly states to Matt, “It’s just not going right, and you can’t understand it. Growing up’s hard, ain’t it, kid? Those kids do look up to you, whether you like it or not.” While Matt is convinced to get serious about surfing again and he and Jack subsequently makeup at Bear’s wedding after symbolically sharing a swig of cheap liquor together, the happy reunion is unfortunately short-lived, as all the boys are forced to face the draft board and not all of them are successful in their attempts to scam their way out of fighting in the Vietnam War. Indeed, while Matt manages to dodge the draft by pretending to be a barely mobile cripple with an antique Forrest Gump-esque leg brace and Leroy gets out by merely exaggerating his madly masochistic tendencies after a darkly humorous encounter with a military psychologist played by Joe Spinell that ultimately has him strapped to a stretcher and hauled off to a loony bin, Jack and their mutual friend ‘Waxer’ (Darrell Fetty), who unsuccessfuly pretended to be a flamboyant homo to get out of military service, are drafted, with the latter ultimately dying in the war.

As the coarse horse-voiced quasi-commie agitator Robert Zimmerman once arrogantly yet rightly sang “The Times They Are a-Changin” and working-class hero Matt is certainly not happy with it, especially after going to a local restaurant with his baby-momma Peggy to get a cheeseburger and being told by a repulsively effete long-haired burnout hippie server, “We’re off that trip. We don’t serve animal hostilities. Dead flesh.” While Matt yells at the hippie server in a threatening manner, “I’m not your brother…and turn down that crappy music,” he must live with the fact that blacks are burning down American cities and that spoiled white hippie degenerates have turned rebellion into a lame form of slave-morality-based social signaling where the weak and meek are worshiped and all forms of Occidental traditional and morality are mindlessly mocked and demonized by people that lack the self-discipline and moral fortitude to even be able to uphold such values. Not surprisingly, Matt and his friends are fairly apolitical individuals that care more about their friends and personal lives than abstract political ideas, yet it is quite obvious that they loathe hippies and are disillusioned with they way that the country is heading. All of this occurs during the third chapter of the film entitled “THE NORTH SWELL – winter 1968.” After attending the premiere of a surf film entitled Liquid Dreams that leaves him somewhat upset when spectators mock a small excerpt of the surf movie that he appears in, Matt seems like he is totally done with surfing and he is only coerced into getting back onto his surfboard when Jack randomly comes back after serving in the Vietnam War. Indeed, instead of going to see his estranged girlfriend Sally, Jack immediately goes to the beach in his military uniform where he soon reunites with his best bud after playing with his pal and Peggy’s toddler daughter Melissa.

While Jack has a great time catching up and riding waves with Matt, he is startled upon going to visit his longtime girlfriend Sally and discovering that she has married someone else without even telling him. As the film hints in a less than subtle fashion, it seems that, for most people, life only gets shittier and shittier as the years pass, especially if you were a hot shit during your teenage and early adult years like Matt and his surfer homeboys. In tribute to their fall comrade Waxer—a lovable lunatic that wore a Nazi jacket and would ironically die in the Vietnam War wearing a lame looking American uniform—Matt, Jack, and Leroy drink some wine at his grave one night and pay tribute to his memory. Although a man of very few words, Matt breaks down and manages to articulate his brotherly love for his comrade and declares in memory of Waxer, “I’d just like to say…he was a good surfer…and a really great guy. He had a nice cutback. He rode the nose real well. He was kind of screwed up, they way he treated women…but he always got the one he wanted, so it doesn’t matter anyway, because he was just a good guy all the way around. He’d always give people waves. Just give them away. He’d always stick up for his friends in a fight. He wasn’t worth a damn, but he was always right in there. I don’t ever remember a day Waxer wouldn’t go ride with his friends. Waxer was our friend. He was a little part of us. And we’re gonna miss him.” Of course, Matt's word somewhat epitomize the loyal brotherly spirit of the Männerbünde. After paying tribute to Waxer, the three friends go their separate ways.

The fourth and final chapter of the film is entitled “THE GREAT SWELL – spring 1974” and, as the narrator states at the beginning of this segment in a manner that makes him sound like a metaphysician of surfdom, “Who knows where the wind comes from? Is it the breathe of god? Who knows what really makes the clouds? Where do the great swells come from? And for what? Only that now it was time…and we had waited so long.” As a result of a ‘The Great Swell’ that he and his friends have been virtually waiting their entire lives, Matt attempts to hunt down both Jack and Leroy, but he has no luck and eventually gives up. After failing to find his friends, Matt visits Bear at a pier at night to bring the bad news and is surprised when his mentor gives him his legendary Excalibur-like longboard. Indeed, after giving Matt the surfboard and joyously declaring, “She’s yours man,” Bear, who is clearly in a thoroughly inebriated state, breaks down and confesses to Matt during a rather vulnerable moment, “You know, all these years, there were damn few things that mattered. But the thing that mattered the most…was knowing how you three felt about me. That you respected me…and that you felt I had given you something.” After giving him the unfortunate news that he could not locate Jack or Leroy, Matt attempts to talk Bear into coming home with him to eat dinner with and hang out with his family, but the discernibly dejected dipsomaniac becomes somewhat irritable and demands that he leave without him. Needless to say, Bear is considerably less grumpy the next day when he goes to the beach and discovers that the three friends have been reunited on a particularly sunny morning while gloriously monstrous 20 foot waves are brewing.

Ultimately, ‘Big Wednesday’ is the day where, as long ago prophesied by Bear, Matt and his friends figuratively draw the line in the sand and establish themselves as true surf legends that have reached their peak in terms of both personal and collective accomplishment. When Matt arrives at the Point on the big day, he notices seemingly hundreds of people watching from a cliff as lifeguards try in vain to force surfers to get out of the water since there is a riptide and the waves are getting rather large and quite deadly. In a rather uplifting scene where the friends are both literally and symbolically reunited, Matt makes his way down the steps of the ruined beach gate and is delighted to discover that both Jack and Leroy are waiting for him at the bottom with their surfboards, as if they somehow had the intuition to be at the beach on exactly the same day at exactly the same time. At around the same time Matt arrives, Gerry Lopez (real-life Hawaii-born surf legend of the same name portraying himself)—the hottest new young surfer in the world—also shows up and proceeds to ride the same waves with the protagonist and his friends, though there is no real sense of rivalry between the men. Abandoning all forms of fear and hesitation, the all-blond trio bravely rides a series of very potentially deadly 20-foot waves while Bear watches from the beach with devout admiration, as if he were a father admiring the accomplishments of his grownup sons. Indeed, Matt and his friends are so entrancingly triumphant with their wave-riding that even professional surfer Lopez looks on with great respect and admiration, as if he did not expect to be surrounded by old dudes that couple keep up with him.

Of course, all good things must come to end and the trio decides to quit while they are ahead after Jack and Leroy are forced to bail their boards and pull Matt out of the sea after he has a terrible wipeout and injures his leg. After emerging from the ocean, a young blond surfer dude hands Matt his board and states to him in a meek and extremely humble fashion as if he were in the presence of a god, “This belongs to you. I’ll tell you what, that was the hottest ride I’ve ever seen. I just wanted to tell you that.” Somewhat symbolically, Matt gives the surfboard to the young man and states, “Keep it. If it ever gets big again, you can ride it,” thus signaling that that the protagonist is passing on Excalibur to the next generation in what ultimately proves to be a somewhat bittersweet scene where the hero accepts the fact that his great lifelong journey is finally over and that he must retire to a life of domestic banality. Meanwhile, a younger surfer asks a rather jolly Bear if he surfs and he humbly replies in a somewhat humorous fashion, “Not me. I’m just a garbage man. See you around,” thus indicating that the master feels that his job is done when it comes to preparing Matt and his friends in terms of reaching their full potentially and establishing an enduring legacy. After walking up the stairs of the beach entrance, Matt remarks to his friends, “Lopez. He’s as good as they always said he was” and Leroy replies “So were we.” After Matt remarks, “We drew the line,” he says before completely parting ways with Jack and Leroy, “keep in touch.” Of course, the titular ‘Big Wednesday’ session was the group’s swansong to surfing and it would almost seem blasphemous if they were to actually keep in touch as the trio has reached their zenith in terms of both surfing and their friendships.

Notably, in the Blue Underground featurette Capturing The Swell (2003), Big Wednesday director John Milius states regarding the commercial failure of his film and the ruthless reviews it received, “Oh, it was totally received horribly…attacked by every critic, you know. I was called a Nazi. I don’t know why I was called a Nazi, because I guess I was a surf Nazi […] It was just totally lambasted and I was excoriated to the point where I remember taking a long walk one night, wondering if I should join the French Foreign Legion…but I didn’t.” Despite being an abject commercial and critical failure, Milius has described the cinematic work as being, “In many ways, it’s my most beloved movie,” which is no surprise considering it is both his most personal and autobiographical cinematic work and surely a flick that is more timeless and artistically merited than his hits like the big Cold War agitprop cumshot Red Dawn (1984). Of course, despite being a failure at the box offices, Big Wednesday has developed a loyal following over the decades in both Europe and the United States and is now a beloved cult item that has outlived most of the degenerate leftist film critics that trashed it when it was initially released. In terms of celebrities, Quentin Tarantino of all people has described it as one of his favorite films, even though he hates surfers, or as he once stated himself as revealed in the book Quentin Tarantino: Interviews (1994), “I don't like surfers; I didn't like ‘em when I was growing up. I lived in a surfing community, and I thought they were all jerks. I like this movie so much. Surfers don't deserve this movie.” While Tarantino loathes real surfers, he is somewhat strangely quite fond of imaginary intergalactic surfing superheroes like the Silver Surfer, but I digress.

As someone that has spent a good portion of my life living at the beach, I probably have more direct personal experience with surfers than Tarantino, especially since I would oftentimes spend hours a day with them at local skateparks where they would typically ride longboards instead of regular sized skateboards, yet I loathed many of these individuals for quite different reasons than the repugnantly pompous pop filmmaker. In fact, the reasons I disliked these individuals were for reasons that would probably influence Tarantino to like them (after all, like Tarantino, all these guys were proud potheads). Indeed, despite the fact that theses dope-addled ‘dudes’ looked like stereotypical surfers in the sense that they usually had long blond hair, and wore tie dye shirts and hemp jewelry, they spoke a curious combination of old school surfer lingo and ebonics, listened to superlatively shitty gangster rap music, and suffered from the sort of profoundly philistinic generic negrophilia that oftentimes occurs when a person with a fairly low IQ watches too much MTV. Of course, aside from possibly their rebellious spirits, the surfers of today are hardly representative of those depicted in Big Wednesday, which portrays a time when men were still men and ethnomasochism and xenophilia were hardly vogue (indeed, if the film were remade today, it would probably feature a Mexican protagonist that was good friends with a white tattoo-covered tranny and a jive-talking token negro). While just a guess, I am going to have to assume that the last generation of truly subversive surfers with testicular fortitude were probably the guys associated with Southern California punk/hardcore groups of the late-1970s through early-1980s like T.S.O.L. and Agent Orange. Like the character of Waxer in Milius' film, the band members in these groups and punks in these scenes would oftentimes use Nazi imagery as a means to piss people off. Naturally, these bands would also write sardonic songs relating to surfing like “Hang Ten In East Berlin” by D.I., which also makes satirical references to the Third Reich.

A pure-of-heart piece of shameless celluloid nostalgia that, at least visually speaking, feels like it was directed by the subversive surfer son of American realist painter Edward Hopper (though many of the breathtaking ocean and landscape scenes reminded me of the paints of 19th-century German Romantic landscape painter Caspar David Friedrich), Big Wednesday is true masterful proletarian cinematic art in the way that none of the Soviet commie filmmakers could really figure out (incidentally, in Red Dawn, American prisoners imprisoned at a Soviet concentration camp are forced to watch Sergei Eisenstein's anti-Teutonic/anti-Nazi/anti-Catholic epic Alexander Nevsky (1938)), as a shockingly timeless piece of cinema that appeals to the heart and soul of just about any man or boy that understands the value and importance of both manhood and brotherhood. In that sense, the film is certainly more important now than when it was first released, as we now live in a morally, spiritually, and sexually inverted era where even innately masculine institutions like the military are forced at virtual gunpoint to accept the patent absurdity of having supremely mentally defective trannys in dresses as respectable commanders. Certainly, Big Wednesday is one of the only Hollywood films from the 1970s that I can think of that has a truly decent and inspiring message, not to mention the fact that it is decidedly devoid of any insufferable moral posturing or soulless outmoded leftist messages. On a lighter note, the film was a somewhat surprising reminder to me of my love for the beach and ocean. Indeed, while I am nowhere near as physically active as I was as a teenager, I can safely say that, even over the past year, many of my fondest memories involve the beach (though, instead of hanging out with male friends, I was basking in the singular pulchritude of a lady friend that enjoyed disposing of her pesky bathing suit once she has entered the ocean). In fact, after gleefully wallowing in Big Wednesday more than once this past month, I have no excuse but to get off my ass this summer and finally learn how to surf, even if I am probably too old to start my own beach Männerbünde or even develop into a halfway decent surfer.

No comments:

Post a Comment