-Magda von Richthofen zu Reventlow auf Thule

Thursday, July 10, 2014

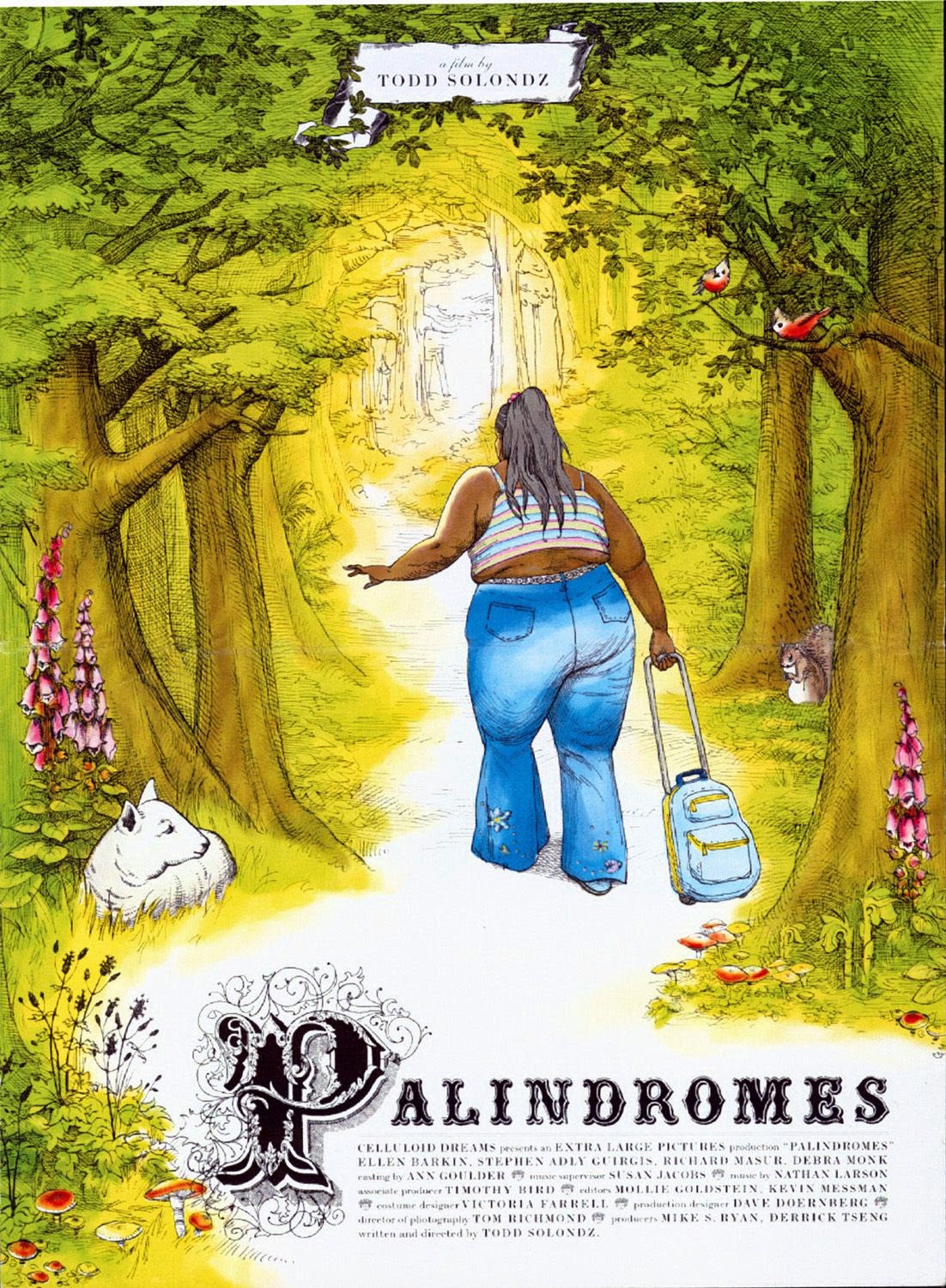

Palindromes

Certainly, virtually every little girl with a truly feminine soul dreams of growing up to be a mother. The inclination to care for another being, especially one of your own flesh and blood, is so strong from an early age that little girls are inevitably stereotyped as playing with baby dolls, an innate desire which eventually prepares them for future motherhood. Of course, the real, tangible future fruition of this childhood, feminine fantasy—having a real baby and the point in time in which one chooses to do so—is determined by numerous, intertwined factors: genetic predisposition first and foremost perhaps (the possibility that our genes are more in control of guiding our destinies than the conscious mind) but with the strong or subtle influence of environmental factors such as one’s family dynamic growing up, surrounding peer pressure, delaying child birth in order to pursue career aspirations, or an unexpected, accidental (or not so accidental) teenage pregnancy. Thoroughly cynical American Jewish auteur Todd Solondz (Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995) and Happiness (1998)) masterfully portrays this topic in Palindromes (2004) with his brilliantly cast showcase of American degeneracy covering the rather unpleasant and controversial subject of abortion as well as pedophilia and kooky, cultish fundamentalist Christians, all delivered in his typically sardonic fashion; this time, however, he delivers with a bit less humor than usual and a much more biting and serious tone which will surely elicit pangs of sympathy and possibly even horror-filled empathy from pro-choice and pro-life women alike, especially those woeful ones of the fairer sex who have themselves undergone an ill-fated abortion (or elicit pride in the thankfully small minority of deluded feminists who believe that abortion is a sacred and celebrated rite of passage which all young women should undergo).

Intended as a sequel to Solondz’s Welcome to the Dollhouse (1995), Palindromes opens by paying homage to the former’s main character, Dawn Wiener, the paltry and pathetic protagonist who has apparently committed suicide after being date raped and falling pregnant with some misbegotten offspring (it is worth noting that Solondz had originally intended for Heather Matarazzo to reprise her role as Dawn but she adamantly refused, leaving him with no choice but to kill off her unfortunate character). Dawn’s brother, Mark, donning stereotypical Jewish garb with mournful Hebraic prayers being sung in the background (and who has apparently become a full-fledged pedophile), steps up to a pulpit beside her casket to deliver a pitiful eulogy to his ever doomed sibling. The scene then cuts to Joyce Victor (played by Ellen Barkin (Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas, Ocean’s Thirteen) and who looks very believable in the part with her cosmetically “enhanced” face and Botoxed to hell trout pout blowjob lips), the do-gooder, liberal Jewish matriarch of the one-child Victor clan, which is of direct relation to the Wiener family, consoling her chubby, adopted black daughter Aviva after Dawn’s funeral as she tucks her in for the night (the entire scene, while appearing utterly ridiculous, is entirely plausible as it is so much the norm nowadays for deracinated whites to be seen gingerly caring for the offspring of other alien races). Aviva joyfully proclaims that she doesn’t want to be anything like Dawn, a total loser, and that it is her greatest and not so unusual wish as a little girl to someday “have lots and lots of babies!” ushering in the main theme of the film: Aviva’s undying maternal yearning and ultimate journey to go about having a baby at any cost, even if it means awkwardly sleeping with and becoming impregnated by virginal, under-aged, spoiled Jewish boys or perverted pedophiliac, racially ambiguous truckers with sickeningly hypocritical Christian bents.

Of important mention here is Solondz’s use of multiple characters of varying ages, sexes, and races to portray Aviva at various points in her journey. I found this unusual and radical filmic device—which calls to mind Luis Bunuel’s That Obscure Object of Desire (1977) in which two actresses alternate in playing the same lead—to be somewhat interesting, but a bit pretentious (while some reviewers take the rather predictable and absurd standpoint that this technique was employed solely to test the viewers’ biases toward certain characters who are facing the same difficult situation, Solondz himself noted, “I just think it’s a neat idea” and also noted how frequently it is used in soap operas and television series, but never “in the movies.”) The film is sliced into chronological chapters, aptly titled with either a blue or pink baby theme and name, to represent whichever incarnation of Aviva will manifest herself, ranging from “Judah” Aviva (who in my eyes represents the most true-to-life Aviva as a young, unattractive, frizzy-haired Jewess of presumably Russian extraction in actuality); to “Henry” Aviva (played by a gawky, red-head who looks like an ardent fan of Blind Melon and who probably believes she died at Woodstock in a past life); to “Huckleberry” Aviva (who is apparently a male but appeared entirely female to me upon initial viewing of the film); to, perhaps most shockingly of all, “Mama Sunshine” Aviva, a morbidly obese negress who bears a striking resemblance to Gabourey Sibide of Precious (2009) fame; to “Mark” Aviva, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh who, in spite of being roughly 40 years old at the time of filming, very effectively pulled off the whole gawky and awkward adolescent girl look, among several other versions of Aviva. In spite of the actors’ vast physical differences, each very effectively and uniformly pulls off being Aviva in spirit: a gawky, 12-year old Jewish girl from New Jersey with a penchant for wearing too tight pants and midriff tops and who is painfully, neurotically soft-spoken, and who, in spite of her bourgeois Jewish upbringing in the suburbs, intrinsically wants nothing more than to live and die by the penis, not as a sex-crazed teenage slut you’d see on the Maury Povich show, but above all else, so that she can become an unwed, teenage mother with “lots and lots of babies.”

Aviva’s journey begins as “Judah” Aviva, a chubby 12-year old Jewess who could easily fit in as the homely, teenage wife of a Rebbe in New York’s Diamond District. Aviva, wearing a too-tight, belly baring shirt and ill-fitting jeans out of which her belly fat seems to pour (as she does throughout the film), attends a summer get-together with her parents at the home of some fellow Jews where she enjoys some alone time with Judah, the other family’s spoiled, overweight, and horny virgin son who has posters of fake-breasted, faux-Aryan porn stars plastered all over his bedroom walls. After rather awkwardly viewing a pornographic film together (and both being seemingly unimpressed with it), Judah and Aviva decide to partake in carnal knowledge together for the first time, albeit for entirely different reasons—Judah, to prove his prowess and finally “make it” with a girl, and Aviva, to get pregnant. Somewhat miraculously, in spite of Judah lasting barely more than 30 seconds, and despite it being her first time, Aviva pulls it off and gets pregnant, giving some credence to the oft-spoken mantra of high school sex-ed that “it only takes once.” After falling ill with morning sickness as the newly incarnated, red-headed “Henry” Aviva, she is found out by her furious parents who, in spite of her pitiful, naive protests to keep the baby, insist that she have an abortion, which her thoroughly leftist, pro-choice mother Joyce justifies by revealing that she herself aborted Aviva’s little brother many years before, citing rather insignificant financial reasons for slaughtering the baby, and that the cluster of cells rapidly dividing within her womb to form into a new human being is, “not a baby—not yet; it’s like it’s just a tumor!” Aviva winds up seeing the same Jewish abortion doctor, aptly named Dr. Fleischer (meaning “butcher” in German) who aborted her baby brother years before, who proceeds to take care of Aviva’s little problem, albeit accidentally giving her a hysterectomy in the process. Upon waking after the ill-fated procedure, Aviva’s parents begrudgingly reveal to her that her misbegotten offspring would have been a girl, opting to leave out the unfortunate, life-transforming bit about her inability to ever conceive a child again. In the aftermath of this traumatic situation, and still with the undying desire to have a baby at any cost, Aviva decides to run away from home and hitchhike to wherever she may find some easily obtainable, wanton, and wayward source of biological gold (semen).

As “Henrietta” Aviva (who looks very much like “Judah” Aviva), the desperate teen attempts to hitch a ride with any stranger who is willing to pick her up on a busy New Jersey freeway. Coincidentally, Dawn Wiener’s pedophile brother, Mark, who is driving an old clunker Mercedes Benz, picks her up at the side of the road, imploring her to let him take her home. She coldly and adamantly refuses, and he goes on to explain to her that her name is a palindrome, meaning that it’s spelled the same way backwards as forwards (as the director put it, “this functions as a loose metaphor for the ways in which we don’t change…the nature of the film explores that part of ourselves which does not change, which is one of the films central themes: change vs. stasis”). Aviva agrees to wait in the parking lot in his car while he runs some errands. Instead of waiting, however, Aviva jumps into the back of a truck in the parking lot having no clue, nor caring, where it may eventually lead her. Aviva winds up in the front passenger seat with the truck driver many miles into the journey (presumably somewhere in the south), and that night, the pernicious, yet awkward pedophile winds up defiling her the Catholic way in a budget motel. The next morning, “Joe,” a somewhat strange, racially ambiguous cross between a wop and a redneck with a predilection for flannel shirts, deserts Aviva leaving her on her own again, sexually satisfied yet obviously fearful of being caught for his thoroughly perverse butt-buggering of a preteen girl. Like most idiotic teenage girls who come into contact with pedophiles, Aviva seems rather enamored with and fawns over the much older, lascivious lumberjack-like trucker, seemingly the first male to give her any real attention, softly remarking before he makes his stealthy exit that for her, “last night was…beautiful,” not realizing he’s a filthy pervert who’s only looking to take advantage of her. Abandoned and dejected, Aviva is incarnated as “Huckleberry” Aviva, in actuality a boy who looks like a dykey mid-western teenage girl, and traverses by foot the nearby countryside, eventually hopping on what appears to be an abandoned Fisher-Price children’s boat in a lake and floating, somewhat symbolically in a biblical sense, downstream, destination unknown.

Awakening on a shore in the middle of the woods as perhaps her most curious incarnation, “Mama Sunshine” Aviva, a morbidly obese, middle-aged black female, Aviva meets Peter Paul, an overly friendly and helpful, cystic-fibrosis addled youth who has stumbled upon her (of obvious Semitic extraction and who could easily pass for Ben Stein’s son), who unquestioningly welcomes her into his adopted family, the Sunshine clan, a group of fundamentalist Christians (and very obvious contrast to Aviva’s liberal, Jewish family), who have adopted a motley crew of assorted retarded and deformed children (who would have otherwise been aborted had their mothers not been totally out of their minds on drugs, retardation, and/or religion), including a blind, albino Nordic girl, a creepy and flagrantly faggy twink with a boyish bowl cut (who seems to have nothing wrong with him except that he looks like he could have easily starred in some degenerate trash twink porn), an Indian midget with a barely intelligible lisp, a characteristically chipper boy named Skippy with Down Syndrome, and a mulatto flipper baby, all of whom are cared for by “Mama Sunshine,” a kind and matronly big-bosomed, Borreby Jesus fanatic who presumably couldn’t have children of her own and so graciously took on “the Lord’s work” by adopting and caring for a veritable zoo of every type of retard known to man. Soon after arriving at the Sunshine home, Aviva falls into a deep sleep, during which Mama Sunshine has her examined by the family physician, “Dr. Dan”, who determines that she is sick from dehydration. After waking up and rather flagrantly but convincingly lying about her dubious origins (citing that her parents had been killed in the 9/11 attacks, that her kindly grandmother died of brain cancer, and that her cruel, evil foster parents abused her), Aviva is warmly welcomed into the family by Mama Sunshine who dresses her in a matronly pink dress that when adorned by this particular incarnation of Aviva very effectively evokes the image of the shrimp n’ grits makin’ “Mammy” caricature of the antebellum south.

Aviva takes a walk with Peter Paul in which he leads her to a nearby, abandoned tract of land where the dismembered parts of aborted fetuses are illegally disposed of in plastic bags, along with various other assorted garbage. Horrified and screaming after Peter Paul innocently picks up a bag of guts to show to her, the two kneel down and say a prayer for the unborn children, which is bizarrely punctuated with a kiss as Peter Paul seems to have an unrelenting crush on Aviva. Around this time, he also reveals to her that the family has a good friend, a man named Earl, who was once a convict but has since reformed himself as a born-again Christian, who lives in a trailer near the family’s property. Later that day, after being welcomed into the physically deformed, yet spiritually perfect family and even joining the family’s Christian pop group, “The Sunshine Singers,” in which the children ecstatically sing (sometimes almost eerily erotically so in mainstream pop fashion a la Britney Spears or N’ Sync) of their love for Jesus, Aviva shockingly learns that Earl is actually “Joe,” the same man who took her anal virginity in a hotel room and abandoned her just days before, after he shows up with Dr. Dan while the children are performing a dance routine in the family’s basement. The two make eye contact but say nothing to each other, and later that night, as she is spying on the male head of the household, Mr. Sunshine, Dr. Dan, and Earl in a private room in the basement, she learns that Dr. Dan had rather disgustingly taken photos of her genitals while she was unconscious, which he shows to Mr. Sunshine and Earl, remarking with this photographic evidence that Aviva is clearly a “child whore.” The three then begin discussing their plans to assassinate Dr. Fleischer in New Jersey, the very same abortion doctor who very recently performed Aviva’s ill-fated procedure just weeks before. Aviva, still eager to win Earl’s love and affection and hoping to be impregnated by him still in spite of how niggardly he treated her, ventures out into the woods that night to Earl’s trailer, and the two refine the nefarious plan to kill Dr. Fleischer together as a team. The ill-fated duo again embarks for New Jersey, all the while with Aviva coaching doubtful Earl of what he must do, egging him on that it’s god’s will and that the awful abortionist must pay “eye for an eye, tooth for a tooth” style. Earl, a misguided soul who is ever hesitant and indecisive over just about anything he does, quietly pulls up to the doctor of death’s suburban home with his rifle and Aviva at his side, walks up a sliding door and hesitantly pulls the trigger, accidentally shooting Dr. Fleischer’s young daughter in the head and subsequently downing Dr. Fleischer with the second shot. In the terribly tense and uncomfortable scenes that follow, Earl is markedly upset and suicidal over what he’s done as the two find themselves holed up in a local hotel room, with Earl vomiting and lamenting “I did the wrong thing…God hates me…I’m going to fry…I could change, but now I’m going to die.” Like all hormone-addled adolescent girls, Aviva foolishly implores Joe to stop spouting such nonsense and with her undying love and devotion for him, she states that she is willing to take the blame for the murders. Of course, the cops show up in no time and when Joe unwisely goes to the door with his rifle in tow, he intentionally or not commits self-slaughter when he opens the door to a round of bullets puncturing his guts from every which way.

Palindromes begins to wind down with the final incarnation of Aviva, “Mark” Aviva, played by Jennifer Jason Leigh (who, at nearly 40 years old very convincingly plays the angst-addled yet soft-spoken adolescent). It seems at this point that, given her tender age, Aviva was able to legally bypass any responsibility for the events that had transpired in the weeks before, and perhaps in casting her as an older woman, Solondz is demonstrating that Aviva has grown up to some extent, that perhaps she has even changed and matured. However, in this particular segment of her journey, during a family birthday party held for Aviva by her parents, the naive young lady has a rather nihilistic and despairing conversation with Dawn Wiener’s brother, Mark, a recently convicted and now much loathed pedophile who is being entirely ignored and/or reviled by other guests at the party, who wisely asserts and again harkens back to the main theme of the film that, “People always end up the way they started out. No one ever changes. They think they do but they don’t…it makes no difference. You’re essentially the same in front, from behind, whether you’re 13 or 50.” Nowhere is this more penetratingly evident than in the penultimate scene of the film in which Aviva has a clandestine meeting with Judah in the woods who assures her, “I’m a changed man… I think I’ve matured a lot,” who then proceeds to unzip his pants and again have his way with her, only to again fail in lasting any significant amount of time, and with Aviva imploring him to try again, as quickly as possible, because she’s still as eager as ever to have a baby.

In conclusion, Palindromes reminded me somewhat of another Jewish-directed effort, Capturing the Friedmans (2003), directed by Andrew Jarecki in that, much like that film, which rather ambiguously handles the subject of pedophilia, Solondz makes no clear indication with Palindromes as to where he stands on abortion. While he very accurately, yet somewhat negatively portrays the Christian fundamentalist Sunshine family as all out bible-thumping wackos with murderous desires to annihilate abortion doctors, he almost portrays them—a family which cherishes even the most unloved and unwanted of children—in a more sympathetic light compared against the much more liberal Jewish Victor family (a family dynamic with which he is much more intimately familiar) in which unwanted children, physically defective or not, are completely disposable. While on the surface it seems that Aviva’s parents are overwhelmingly caring and only looking out for the best for her (with her own mother even self-critically lamenting toward the end of the film that perhaps she had been a horrible mother, and that she still had the ability to change for the better), it is made obvious by Joyce Victor’s rather callous statements about her own abortion (that she’d done it to financially protect Aviva, such that she’d have as many material possessions as possible growing up versus the much more fulfilling love and memories of a sibling) that perhaps it was rather ironically and hypocritically this decision and her means of raising her daughter that ultimately instilled Aviva with the overwhelming desire to get pregnant, to have a child of her own who would love her unconditionally. In the end, one may never know exactly what it is that drives Aviva so strongly toward conceiving a child in her early adolescent years, but such an insatiable itch is really rather pervasive in the decadent and perverse West, only now most teenage girls are taking it a step beyond simply having a baby, and desperately trying to conceive a very special, ill-fated sort of baby of the brown bastard variety, since it is not simply their own family which has rendered them unloved, but their entire race as a whole. And lastly, while one can argue that all of Solondz’s films have a decidedly Jewish bent about them, and while Palindromes may take a somewhat ambiguous position about abortion, one thing is certain: unlike other Jewish directors, Solondz is hardly sympathetic or kind in his portrayal of his own tribe, instead invariably opting to very honestly and at times crudely portray them, warts and all, as a neurotic group which, while responsible for much of the degeneracy and decline of the west, may ultimately find itself on the same doomed sinking ship in the same stench-filled, muddied waters of multiculturalism and “die-versity” which threaten to drown the whole world.

-Magda von Richthofen zu Reventlow auf Thule

By

soil

at

July 10, 2014

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.

"Butt-buggering of a preteen girl", my dick nearly ripped through my trousers when i read that ! ! !.

ReplyDeleteMagda you`re even more racist than Ty E, aren`t you cheeky ! ! !.

ReplyDeletePalindromes is indeed quite the viewing experience, one that I remember quite well, though it's been years since I last watched it.

ReplyDeleteAnd Solondz has always been interesting in his willingness to extend to his own bunch the same cynicism and examination under harsh lights that he gives to anyone else. Recall the dinner-table argument about the Nazis in Solondz's film Storytelling and how the director gleefully skewered Jews' hyper-sensitivity in regard to perceived anti-Semitism, as well as their utter need to keep Hitler alive as the great bogeyman who -- with the mere mention of his name -- can be used to justify any of the Jews' tribal clannishness, cutthroat competitiveness and psychological manipulation of other peoples.

Solondz, bitches. That morose, four-eyed bastard son of New Jersey gets the Scott Is NOT A Professional stamp of approval.