Wednesday, October 9, 2013

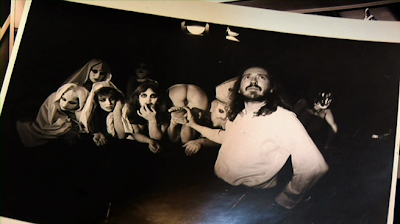

Mondo Lux: The Visual Universe of Werner Schroeter

I typically try to refrain from reviewing documentaries as I see it to be a redundant task for the most part, yet every once and a while I come across a certain doc that needs to be seen and that certainly applies to Mondo Lux - Die Bilderwelten des Werner Schroeter (2011) aka Mondo Lux: The Visual Universe of Werner Schroeter, a strikingly intimate and rather revealing document of the life, artistic works, and remaining days of the notoriously private German New Cinema auteur and dandy Renaissance man Werner Schroeter (Eika Katappa, Malina), arguably the last great 'artiste' of truly decadent (in the positive sense!) Teutonic kultur. Directed by Schroeter’s longtime cinematographer/collaborator Elfi Mikesch (Seduction: The Cruel Woman, Fieber), who shot such Schroeter arthouse masterpieces as Der Rosenkönig (1986) aka The Rose King and Two (2002) aka Deux, Mondo Lux is easily the greatest introduction to the superlatively secret life and kitschy high-camp films of the insanely idiosyncratic auteur, who died from cancer at the age of 65 on 12 April 2010 before the documentary was released, so it should be no surprise that the film has the slightly ominous feel of a living obituary. A theatrically melancholy man who wore all black his entire life and was most obsessed, at least cinematically speaking, with love and death and the link between the two, Schroeter discusses in Mondo Lux the many lovers and family members in his morbidly melodramatic life who succumbed to death at a premature age, typically under tragic conditions, including suicide and complications related to AIDS. Of course, like a Schroeter film, Mondo Lux is not all about melancholia and weltschmerz, but is also quite tragicomedic and features a number of frolicsome anecdotes from his friends/collaborators, including actresses/divas Isabelle Huppert and Ingrid Caven, as well as Germanic filmmakers Wim Wenders, Rosa von Praunheim and Peter Kern, among various others. Easily the most preternatural and least tamable director of German New Cinema, Schroeter’s was also one of the most, if not the most, esoterically influential, inspiring the aesthetics of filmmakers including (but certainly not limited to), Hans-Jürgen Syberberg, Daniel Schmid, Walter Bockmayer, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, and Ulrike Ottinger, yet virtually all of his films are impossible to find in the United States and a number of his films have yet to be released in any home media format anywhere. An art-addled and effortlessly effete aestheticist whose films are virtual living museums of decadent European art history, Schroeter also moonlighted as a documentarian, opera director, and photographer and all of these subjects are covered in Mondo Lux, a virtual Schroeter-for-Dummies guide in celluloid form, but also a must-see for serious ‘Schroeter survivors’ who are more than familiar with his work. Despite Schroeter's reputation for the sadder side of life and that the document follows him as his body becomes weaker and discernibly emaciated from cancer, Mondo Lux—in its depiction of the filmmaker working relentlessly on various projects in a frantic attempt to escape death—is ultimately an inspiring work that makes one want to live life to the fullest, or at least die trying, which the dandyist director of German New Cinema did with a sense dignity that is actually quite shocking, especially for a man that seemed to worship death.

As demonstrated by his various references to great artists/musicians/poets/writers, including Franz Schubert, Heinrich Heine, Robert Schumann, William Shakespeare, and Arnold Schoenberg, among various others, Werner Schroeter is a man that lives and breathes for art, but his choice of medium was cinema, which gave him the opportunity to take an eclectic approach to art and creating delightfully decadent cinematic works like no other filmmaker before that, ultimately achieving the “Gesamtkunstwerk” in celluloid form, albeit in a conspicuously kitschy fashion that proved both “high” and “low” art can be seamlessly synthesized. Filmmaker Wim Wenders—a fellow with a more than flat affect that I would have never suspected had an affinity for a film like Eika Katappa (1969)—describes Schroeter as follows,“I’ve known him since 1967 in Munich. We were all sitting together, 20 students at the film academy, and Werner was one of those twenty. By far the greatest eccentric there. The only dandy in the group. He didn’t stick it out very long.” Indeed, while Schroeter became one of the most original and influential filmmakers of German New Cinema, he couldn't care less, stating, “I have no intention whatsoever of playing a leading part [in the New German Cinema], and submit to the expectations of producing Kulturscheisse [literally, Cultureshit], even if it may be true that I carry around with me and into my films the past of this Kulturscheisse,” thus demonstrating the audacious auteur filmmaker's innate individualism that would ultimately cause him monetary troubles (many of Schroeter's films cost him more money than they made in theaters) as he never had an interest in appealing to mainstream audiences, be it German or otherwise. As semi-snidely Schroeter explains in a speech featured in Mondo Lux regarding the lack of respect he received in Germany for creating aesthetically audacious and largely apolitical works, “here I was seen as the crazy enfant terrible. The singing, jumping art cunt or whatever. People thought little of my intelligence. Whereas in France I was seen as an equal partner,” hence the filmmaker’s decision to make a good percentage of his films outside of his homeland, including two Pasolini inspired “Italian eros” works, including Nel regno di Napoli (1978) aka The Kingdom of Naples and Palermo oder Wolfsburg (1980), as well as two French co-productions with French actress Isabelle Huppert, including Malina (1991) and Deux (2002) aka Two, among a number of other cross-cultural European cinematic works. In regard to Palermo Oder Wolfsburg, Schroeter states in Mondo Lux that the work is, “An accidental encounter between Italy’s South and what I don’t like about Germany, such as Wolfsburg. And VW,” thus hinting at his hatred for not only industrialization and capitalism, but also the Third Reich, the latter of which he would lampoon in his underrated film Der Bomberpilot (1970), the closest thing the auteur ever made to a Nazisploitation flick.

Of course, more than anything, it was Schroeter’s muse Magdalena Montezuma (Willow Springs, Freak Orlando), who died tragically at the mere age of 41 in 1984 from cancer of the womb, that his filmmaking changed forever and arguably for the worse, but luckily the two collaborated on one last work, Der Rosenkönig (1986) aka The Rose King, while the actress was literally dying, which, at least in my opinion, turned out to be the director’s celluloid magnum opus. Discovering Greek-American soprano diva Maria Callas at age 13 shortly after his Polish grandmother committed suicide was an aesthetic ‘revelation’ of sorts for Schroeter and he paid tribute to her with not only his first 8mm film Maria Callas Porträt (1968), but also throughout his entire career via her songs and essence haunting a number of his films. On top of his Polish grandmother, baroness Elsa von Rotjov, committing suicide when he was only 13, Schroeter’s first lover Siegfried committed suicide when he was 13 or 14 and the boy was 16, not to mention that two of his other boyfriends died under tragic circumstances, one of which died from AIDS. One of Schroeter’s lovers that did survive is Berlin-based filmmaker Rosa von Praunheim (Army of Lovers or Revolt of the Perverts, A Virus Knows no Morals), who is featured throughout Mondo Lux reminiscing with his lunatic lover over the good old days, including how the Berlin buggerer used to emotionally brutalize his beau. Of course, von Praunheim was not the first person to attack Schroeter as the filmmaker discusses in Mondo Lux how he was regularly beaten up as a child, even having urine dumped on his head. More than anyone, Isabelle Huppert, who did a photo shoot with the dandy auteur before he died, drives home the fact that Schroeter approached all artistic mediums the same way, with a uniquely uncanny creative energy, which is quite apparent to anyone that has seen his films. As for Schroeter himself, he described the driving force behind his films as follows, “Of course humor, farce was a mode of expression I really enjoyed. I wanted to express myself with people I lived with. And that’s what interested me. My films at the time are by-products of my love affairs,” and, indeed, judging by virtually any of his tragicomedic films, it is easy to see that the keenly cosmopolitan kraut with a Mediterranean soul was perennially lovelorn.

Not long before he himself also died of cancer on 21 August 2010, German auteur Christoph Schlingensief (Egomania – Island without Hope, The German Chainsaw-Massacre) wrote in his blog that he hoped that Werner Schroeter’s films would reach a larger audience and make their way into film school curriculum, which, although would be great, is rather unlikely as his cinematic works only seem all the more hermetic and impenetrable as the decades have passed and as the great Teutonic philosopher Oswald Spengler once stated, “One day the last portrait of Rembrandt and the last bar of Mozart will have ceased to be — though possibly a colored canvas and a sheet of notes will remain — because the last eye and the last ear accessible to their message will have gone,” which is even more true when it comes to man who directed Malina (1991), a macabre, if not sometimes merry, mindfuck of a movie about a man named Malina. Prophesied in 1977 by his butt buddy R.W. Fassbinder as likely to “assume a place in film history similar to that of Novalis, Lautréamont, and Louis-Ferdinand Céline in literature,” Schroeter, as the title of Mondo Lux: The Visual Universe of Werner Schroeter makes quite clear, not only created his own cinematic language and universe, but proved that cinema could be aristocratic, even if it features drag kings and queens, as well urolagnia among lesbo mental patients as surreally scatalogically depicted in Day of the Idiots (1981) aka Tag der Idioten. As Mondo Lux director Elfi Mikesch stated in an interview with filmmaker Frieder Schlaich (Paul Bowles – Halbmond, Otomo) regarding the death of Schroeter and the importance of his films, “I just have to get used to the fact that this will never happen again. That’s why his films have become so important. They are what remains. All these waste products survive. There’s a lot to learn and experience from them. Every time I watch one, and I watched many recently, I discover something new, and surprising new threads in his oeuvre. Whether it be body language, the relation between language and music and how that relates the spoken word, to physical action or the representation of vision. The way he presents speech and music. That is incomparable, it raises your consciousness.” While still alive, Schroeter was no less complimentary of Mikesch, writing of their seemingly immaculate creative partnership that began in 1986 with Der Rosenkönig, “From the beginning on, we had a specific communication code and very deep trust. While Elfi’s poetry is different from mine, it is equally multi faceted. Elfi gives the content of many images a structure, and she derives poetry from it. In my case, the poetry originates from the void, in Elfi’s from motion and condensation. This overlap enables us to collaborate,” thus it should be no surprise that he entrusted her to direct Mondo Lux, a documentary that, at least in my quasi-humble opinion, is easily the greatest tribute from one filmmaker to another as the last testament of a truly avant-garde auteur that never got his dues in terms of his importance and prestige as one of cinema's few true artists and innovators.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

October 09, 2013

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.

He was a dirty queer which negates him and everything he ever did.

ReplyDeleteWith regards to that quote from Oswald Spengler about Rembrandt and Mozart, wasn`t he just refering to the fact that at some point "THE TIME OF SEXUAL REPRESSION" will be brought to a thankful and merciful end, at which point people will simply no longer have any interest in pretentious, highbrow, elitist, artsy-fartsy, bull-shit anymore. All they`ll want to do is fuck ! ! !.

ReplyDelete