Undoubtedly, if I were to guess what film that I have seen the most times, it would surely be Alex Cox’s absurdist and sardonic dystopian punk sci-fi masterpiece Repo Man (1984)—a work that I have no problem admitting that I watched at least twice a day for about a month a couple years back. Although I first saw Repo Man when I was around 12 or 13 years old, it would be a decade before I developed the deep admiration and obsession with the film that I have today, which is rather odd considering my teenage appreciation for early 1980s punk/hardcore has all but totally fizzled out since then yet Cox’s film is one of the very few ‘punk’ films that actually has the authentic attitude as a fiercely farcical work where legendary “man’s man” John Wayne—the Irish-American draft-dodger who provided the countless American males with enough romancing of battlefields to fight it in virtually every war of the second half of the twentieth century—is described as a fag and where Emilio Estevez sings the Black Flags ‘blues.’ With uniquely unhinged references to UFOs, Jungian psychology, rabid Reaginism, Televangelism, Scientology and other chic cults, the ‘Reconquista’ of California by Mexico, psychotic yuppie materialism, crackpot conspiracy theories, nuclear war, youthful middleclass nihilism, and the apocalypse in a world of aberrant spirituality, pathological paranoia, and all out cultural chaos, it is nothing short of absolutely amazing that Repo Man was ever released by Universal Studios—a studio that stands for everything that Cox’s film is against as a work with an unlikeable anti-hero as a protagonist and a cast of totally corrupt characters, an anti-romantic subplot, and an unwaveringly anarchic, misanthropic, and pessimistic essence where the American dream has been replaced with a pleasantly pernicious punk rock nightmare of the tragicomedic sort. Released in the fitting Orwellian year of 1984, Repo Man features a world all the more negative and nihilistic than that of the Orwell novel as the characters of Cox’s are far too apathetic and infantile to have thought-crimes and are far more interested in beer, money, drugs, joyless sex, infantile rock n roll, television, and pseudo-religions/cults to get involved in any sort of humanistic people’s revolution. Featuring a punk/hardcore soundtrack that acts as an imperative ingredient of the film, including songs from Black Flag, the Circle Jerks, Iggy Pop, Suicidal Tendencies, and the Plugs, Repo Man, despite being directed by a Brit, probably does the best job out of any film of its time at portraying its particular zeitgeist because it depicts all groups and subcultures that Hollywood never gave a 'serious' voice, including braindead punks, mischievous mestizos, middle-aged ex-hippie burnouts turned Christian burnouts, trendy cult groups, and members of various loveable lunatic fringe groups. Indeed, the genius of Repo Man is that by using absurdist Buñuel-esque satire and anarchic sardonic slapstick of the very vaguely Italian Neorealist and Spaghetti Western sort, Cox was able to hysterically and humorously highlight everything that made the 1980s one of the most repugnant eras of the twentieth century, even if it sired a timeless cult classic like Repo Man as a result of such culturally crappy circumstances.

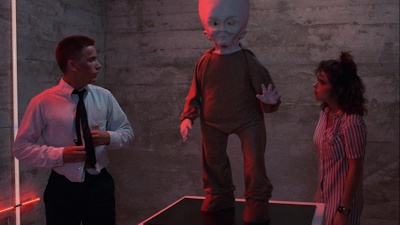

Dullard punk rock dude Otto Maddox (Emilio Estevez) has one of the worst days of his rather mundane and aimless life after he is fired from his job as sales clerk at a grocery store and later walks in on his beauteous yet bitchy dark-skinned punkette girlfriend Debbi (Jennifer Balgobin) making out with his dumbass small-time crook best friend Duke (Rick Rude) at a suburban punk rock party hosted by his nerdy ass-kissing friend Kevin (Zander Schloss)—a goofy fellow who bears a striking resemblance to Napoleon Dynamite. With neither a job nor a girlfriend, Otto aimlessly walks through a Mexican ghetto and is approached by a corpse-like conman named Bud (Harry Dean Stanton), who offers him $25.00 to drive ‘his’ other car to another location and becomes a repo man in the process after unwittingly repossessing the car of a deadbeat Hispanic for an absurdly generically titled repo company called “Helping Hand Acceptance Corporation.” Although initially ambivalent to brazen bitter bastard Bud and his motley crew of wisecracking repo men, and only deciding to take the job after finding out his ex-hippie pothead parents donated all his graduation money to a megalomaniacal televangelist, Otto eventually comes to appreciate the fact that “the life of a repo man is always intense.” Otto becomes the protégé of Bud, who teaches him the “Repo Code,” and the two subsequently snort coke, battle a rival gang of Hispanic repo men named the Rodriguez Brothers (Del Zamora and Eddie Velez), get involved in “real-life car chases” and repossess countless cars together. A sassy (and apparently Sapphic) black chick named Marlene (Vonetta McGee) also works at the repo company, but she is a secret traitor in cahoots with the Rodriguez brothers as a Marxist revolutionary of sorts from people varying from pompous preppy pricks to kindly old black grandmothers. Otto also learns the trick of the trade from a pimp-like black repo man named Lite (played by Cox regular Sy Richardson)— a man who literally breaks every segment of the "Repo Code"—and reluctantly takes spiritual advice from deranged junkyard guru named Miller (Tracey Walter) who promotes pseudo-Jungian theories, including “the lattice of coincidence” and something he calls the “cosmic unconsciousness,” which is clearly a bastardized take on Jung’s psychoanalytic theory of the collective unconscious. Meanwhile, Otto’s ex-best friend Duke, ex-girlfriend Debbi, and another Mohawk-sporting punk named Archie (Cox regular Miguel Sandoval) have formed a criminal punk gang that commits a number of armed robberies against various convenience stores and factories. Otto also starts a rather ridiculous non-romantic relationship with a bat-shit crazy and exceedingly annoying bitch named Leila (Olivia Barash) who is part of a “secret network” under the aptly titled named “United Fruitcake Outlet” that is dedicated to exposing the U.S. government’s cover-up of UFOs and space aliens. Leila also tells Otto about a mysterious 1964 Chevrolet Malibu from Roswell, New Mexico that contains four dead yet decidedly deadly space aliens in the truck. Although Otto thinks the little lady has more than a couple screws loose (despite screwing her), the next day he learns there is a $20,000 reward for the recovering of the Malibu, which is being driven by a determinedly deranged dude named J. Frank Parnell (Fox Harris) who stole the alien corpses from a Los Alamos National Laboratory and whose acute cognitive dissonance is the result of a lobotomy, as well as extraterrestrial radiation that is seeping out of his truck.

Naturally, a number of parties start searching for the radioactive Malibu, including Otto and Budd, the Rodriguez brothers, Leila and her loony friends, Debbi and Duke’s gang (who actually just steal the lucky car by happenstance), but also a group of all-blond Aryan federal agents led by a frigid fuehrer bitch with a bionic New Romanticist-style hand named Agent Rogersz (Susan Barnes), whose character seems to be modeled after fashion designer Anna Wintour and who rightfully proclaims, “No one is innocent,” at least in the ridiculous realm of Repo Man where everyone is looking out for #1. Even loveable bastard Bud begins to break his own code when his ever growing fanaticism for obtaining the hefty monetary reward for the Malibu gets the better of him, thereupon leading to his inevitable demise, but leaves with the sagely words of wisdom, “I'd rather die on my feet than live on my knees.” In the end, it is the wildly idiosyncratic, idiot savant crank Miller—the man who stoically proclaims “John Wayne is a fag” and “the more you drive the less intelligent you become”—who is the only person who has the power to master and maneuver the extraterrestrial-fueled Malibu and Otto—the formerly apathetic yet nihilistic and hateful suburban punk—has finally found a calling in his life, thus also enabling him to take a ride in the alien automobile, thus concluding on a rather positive note for a film that restlessly wallows in cultural pessimism of the apocalyptic sort.

In an interview featured in the book Destroy All Movies!!! The Complete Guide to Punks on Film (2010), Repo Man director Alex Cox stated, “I was certainly interested in punk, but as a revolutionary movement rather than a fashion thing. In that sense, as Buñuel said about Surrealism, the movement completely failed. But it was inspiration for a while.” And, indeed, while being the indisputable quintessential ‘punk film,’ Repo Man makes a mockery of the fact a good percentage of punks are spoiled middleclass morons who have no real reason to wage a mindless war against society, especially since Mexicans and hobos are literally dropping like flies in the gutter in the film. As for the protagonist of Repo Man, Cox stated, “Otto is more a blank page than an everyman, I think. What I found interesting in his character was how a supposedly “counterculture” character like a punk rocker could be quickly assimilated into a reactionary and hierarchical system—in this case the repo business, but it could also be the military, say—without even changing his appearance; the Suicidal Tendencies T-shirt was replaced by a suit jacket but the haircut remained the same.” Rather ironically, despite Cox’s talk of a “reactionary” system, it is only when Otto learns the “Repo Code” from Bud and learns to master his job that his life develops meaning and that he is able to shed his uncultivated hatred and nihilism, hence why he later symbolically states later in the film “I can't believe I used to like these guys,” in regard to the alpha punk group the Circle Jerks, who have now degenerated into a goofy lounge act (in real-life, the band actually devolved into a second-rate metal group). On top of that, it is through supposed wack-job messiah Miller that he develops the sense of spirituality that he so bitterly fought against throughout Repo Man. Indeed, it seems that while punk rockers always glorify disorder, mindless and fruitless libertinism, and anarchy, their innate inner need to rebel against society is a direct result of their hatred for the spiritually degenerate and cultureless society full of chaos and dysfunction that makes up the modern world, where nothing is sacred and those that claim to be are carny frauds and false prophets who like to earn large profits like the televangelists and Scientologists. Indeed, it is only the biggest losers of losers who never grow out of punk as it is a sign of a sheer and utter lack of maturity and self-control, hence why Otto's punk friends meet grizzly and patently pointless ends.

Released the same years as the other big LA punk rock flick, Suburbia (1984) directed by Penelope Spheeris, Cox’s Repo Man topples over its cinematic counterpart in aesthetic, sentiment, and attitude. While Suburbia has a slave-morality-driven, victim-based attitude of ’Tis a Pity We Are Poor Punk Who Get Beat Up By Rednecks,’ Repo Man takes a look in the figurative punk rock mirror and reevaluates the whole Weltanschauung for the disastrous dead-end drive into a dilapidated ghetto brick-wall that it is. That being said, Repo Man is one of the few artifacts of punk—be it film or otherwise—that has aged quite gracefully as a potent piece of charmingly cynical celluloid that totally philosophically destroys the degenerate subculture it depicts, while having more of a punk attitude than the majority of things that are labeled ‘punk,’ including the bands featured on the film's soundtrack. As much as I absolutely loath automatons who incessantly quote stupid Hebraic Hollywood comedies and other culture-distorting swill, I would be lying if I did not admit that Repo Man is one of the most compulsively quotable films ever made as one would be a pretentious poof not to admit that such lunatic lines like “Goddamn-dipshit-Rodriguez-gypsy-dildo-punks” and “You hear the most outrageous lies about it. Half-baked goggle-box do-gooders telling everybody it's bad for you. Pernicious nonsense. Everybody could stand a hundred chest X-rays a year. They ought to have them, too,” are words of charmingly crude, comedic genius. Indeed, director Alex Cox must have been an alchemist during a previous life, as he turns everything that is American Kulturscheisse into jarringly jocular celluloid gold via Repo Man, so it is a shame that his long-in-the-make non-sequel Repo Chick (2009) is one darkly retarded piece of undignified digital diarrhea that should be absolutely avoided at all costs, especially if one values their personal integrity and/or god given right to think. As a proto-X-Files except all the more mirthful and conspiracy-driven, a hysterical history lesson in conman counterculture spirituality, a jaded jukebox of the best of 1980s LA punk rock, a celluloid rehab program for dumb young punks everywhere to reconsider their worldview, a politically incorrect lesson in Yank class and racial relations, and a rare, highly quotable comedy that does not result in the cinematic equivalent of a lobotomy, Repo Man is indisputable proof that the death of the West can be looked at as a tragicomedy that one can learn many lessons from, at least until an apocalypse or space aliens wipe us out.

As psychoanalyst C.G. Jung wrote, whose theories are not playfully parodied in Repo Man for nothing, “Our present day observations of Saucers coincide – mutatis mutandis - with the many reports going back into antiquity, though not in such astonishing frequency as in these times. But the possibility of the destruction of a whole continent, which today is in the hands of politicians, has never existed previously.” One of the first major thinkers to take the post-WWII UFO phenomenon seriously and actually study it, Jung ultimately came to the conclusion that, although not completely rejecting the idea of real-life little green men from outer-space, UFOs might have a primarily spiritual and psychological basis as he believed modern Occidental man was suffering from a crisis of the mind and soul. Indeed, when maniac Miller seemingly schizophrenically states, “There ain't no difference between a flying saucer and a time machine. People get so hung up on specifics they miss out on seeing the whole thing,” he is essentially pointing to the fact—whether he knows it or not—that all these weird phenomenons and alien sightings have a common origin; an all-encompassing Weltschmerz and deadlock of the Western collective unconsciousness. That being said, it would not be an exaggeration to say that every Western man is seeking to obtain what Otto achieves by the conclusion of Repo Man as a middle-class nihilist man who achieves spiritual and emotionally ecstasy by finally riding in the radiation-run Malibu spaceship/time-machine as opposed to merely getting a mere passing glimpse of it. Of course, as Miller once so famously stated, “The life of a repo man is always intense.”

-Ty E