Wednesday, May 21, 2014

Dillinger Is Dead

Italian auteur Marco Ferreri (La Grande Bouffe, Bye Bye Monkey) was undoubtedly one of the most hardcore, nihilistic, and eloquently hateful European filmmakers of his generation, with a number of his films seeming like, on retrospect, nothing more than sick celluloid novelties that were made specifically to terrorize the bourgeoisie and to totally destroy the filmgoing experience for people altogether. In fact, in a 1977 interview, Ferreri made the following declaration: “The values that once existed no longer exist […] The family, the bourgeoisie—I’m talking about values, morals, economic relationships. They no longer serve a purpose. My films are reactions translated into images.” In what some might describe as his masterpiece, Dillinger Is Dead (1969) aka Dillinger è morto, Ferreri depicted a day in the life of one bourgeois man who gets a little bit of testicular fortitude after discovering German-American gangster John Dillinger’s handgun wrapped inside a newspaper in a closet and decides to run a one-man revolution of sorts by murdering his pill-popper Aryan Barbie doll wife in cold blood, defiling his braindead pop-star-worshipping maid with honey, and disposing of his previous life altogether by jumping into the sea, boarding a luxury ship to Tahiti, and becoming the virtual cuckold of a beauteous virtual goddess, serving her chocolate mousse and what not, with the film concluding with the entire screen being tinted blood red. More of an iconoclastic experiment in social, cultural, and cinematic deconstruction than anything resembling a traditional film with a linear narrative, Dillinger Is Dead features a virtual cipher for a protagonist, next to no dialogue, a misleadingly simple storyline, and an otherworldly ending that is located somewhere between heaven and hell. Directed by a man who once described himself as being, “50 percent misogynist and 50 percent feminist,” Ferreri's film unquestionably features a damning depiction of women as autoerotic automatons that are addicted to effeminate pop stars, prescription drugs, and domestic leisure, yet Dillinger Is Dead is an innately incendiary work where no facet of boobeoise buffoonery is left unscathed and thankfully the film does not wallow in a traditionally idealistic left-wing mode of critique, but instead opts for an aggressively anarchistic approach to the decided destruction of aesthetic, cultural, and socio-political norms. A work said by some to be heavily influenced by Theatre of the Absurd, Dillinger Is Dead indeed defies logic and does indulge in absurdism, with auteur Ferreri once describing the film as “entirely ambiguous” in a 1969 interview, thereupon making for an innately impenetrable film that does offer some critiques and messages, but is ultimately a curious celluloid creature that refuses to be accurately analyzed and classified and thus offers seemingly infinite replay value as a particularly paradoxical work that both infuriates and intrigues like virtually any worthwhile piece of art.

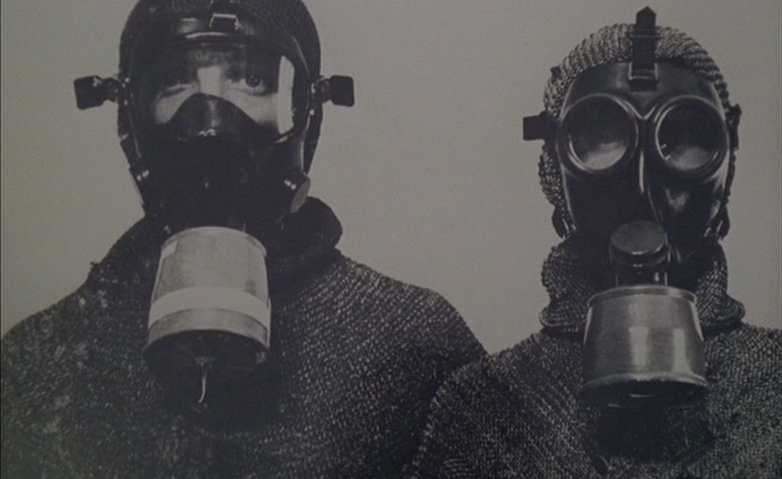

Glauco (veteran French actor Michel Piccoli, who worked with everyone from Jean Renoir to Alfred Hitchcock to Jacques Rivette) is a relatively successful industrial designer who designs seemingly apocalyptic gasmasks for a living and is getting rather bored with his job. At the beginning of Dillinger Is Dead, Glauco is given a demonstration of his latest gasmask in action by and employee and asks his loyal underling to read some notes he has written, which are as follows: “Isolation in a chamber that must be sealed off from the outside world because it’s full of deadly gas…a chamber in which…one must wear a mask to survive…strongly evokes the conditions under which modern man lives. One cannot reflect on this mythical one-dimensional man without analyzing all the characteristics of our industrial society. Nevertheless, a well-drawn metaphor could be very informative and shed light on certain far-reaching consequences that are never explicitly addressed. For example, doesn’t knowing that one must wear a mask create a sense of anxiety? Internalizing these obsessive, hallucinatory needs leads not to an adaptation to reality but to mimicry and standardization, the elimination of individuality. The individual transfers the outside world to the interior. There is an immediate identification among individuals in society as a single entity. One’s needs for physical survival are met by industrial production, which, in addition, sets forth as equally necessary, the need to relax, to enjoy oneself…to behave and consume according to advertising models that render in explicit detail desires anyone may experience. Film, radio, television, the press, advertising and all other facets of industrial production are no longer directed at different goals.” The scenes where Glauco’s notes are read aloud comprise of probably 95% of the dialogue in the entire film, as a work that features incessant monotone talking for the first couple minutes or so and is virtually totally silent for the next 90 minutes or so thereon after. While listening to his own written words, Glauco comes to the natural conclusion that he no longer wants to design gasmasks. Glauco’s assistant confesses he does not understand the final part of his boss’ notes, but he reads them anyway, which are as follows: “Under these conditions of uniformity, the old sense of alienation is no longer possible. When individuals identify with a life-style imposed from without and through it experience gratification and satisfaction, their alienation is subsumed by their own alienated existence.” After getting done at work, Glauco’s assistant hands him a couple reels of film, which contain footage from a vacation, and then the industrial designer heads home and does what he assumedly does every day by basking in his own alienation, but things ultimately change later that day when he discovers a dirty revolver wrapped up in an old newspaper that may or may not have been owned by alpha-gangster John Dillinger.

Upon arriving home, Glauco takes a drag on a cigarette and goes to see his trophy wife Ginette (Anita Pallenberg), who complains about having a headache and refuses to join him for dinner. Glauco goes downstairs and discovers that dinner has already been prepared for him, but he seems to find it inadequate as he puts the food away and begins making his own fancy dinner after referencing a cookbook. After watching a talk show about young teen sluts bragging about wearing makeup in rebellion against their parents, Glauco goes looking inside a closet full of magazines and discovers something wrapped inside an old newspaper, which later turns out to be an old and rather dirty revolver. After unwrapping the newspapers, which features headlines like “Dillinger Is Dead” and “Public Enemy No. 1 Gunned Down Outside Movie Theater” (with real stock footage of Dillinger, including his bullet-ridden corpse, being juxtaposed with the scene), Glauco discovers a black revolver that seems to spark a reawakening in his seemingly impenetrable bourgeois soul. Glauco goes back to work preparing his extravagant feast and his cute pixie-like maid/mistress Sabine (Annie Girardot) arrives at the house. While preparing his food, Glauco begins to literally deconstruct his gun and painstakingly clean every crevice of the weapon with the utmost care, as if it is his baby. Quite notably, the gasmask artisan looks exceedingly emasculate while wearing an apron that undoubtedly demonstrates that the culturally cuckolded character has been domesticated and spiritually neutered by his banal bourgeois existence. While eating, Glauco watches a documentary in tribute to legendary Guido cyclist Fausto Coppi, as well as a documentary on a ‘satellite’ filmmaker of the Godardian sort who uses 70mm film stock and creates so-called “cinemato-physiological” processes. Of course, Glauco is not so hopelessly emasculated that he would go so far as cleaning up his own messes, so he gets his maid Sabine to do it for him, though he decides to eat a second meal while watching a pretentious black-and-white experimental film featuring dirty hippies, including an anorexic black woman that looks more masculine than the white boys featured in it.

After finishing multiple dinners, Glauco finally gets around to watching the home movies that were given to him by his co-worker, which include a bullfight and his scenic vacation to the beach with his wife. While watching the footage, Glauco stands in front of the screen and begins to interact with the images in a seemingly mocking fashion. By the time all the home movies have been completed, Glauco has finished cleaning his revolver and puts it in his mouth as if he has a death wish, even mockingly pretending to blow his brains out. By this time, the industrial designer seems to have fallen completely in love with his gun and decides to personalize it by painting it blood red with white polka dots. After painting his revolver, Glauco attempts to go to bed, but finds himself mildly torturing his sleeping wife (who he previously gave sleeping pills and a douche before she went to bed) by recording her snoring and fiddling with a toy snake over her slightly twitching body. Since his wife does not want to play, Glauco decides to wake up his maid/mistress (who he previously caught kissing a poster of her favorite singer, ‘Dino’) and begins spoon-feeding her watermelon. Instead of having normal sex, Glauco decides to lick honey off of Sabine’s spine while she takes swigs of the sweet stuff from the honey jar. After his strange sexual rendezvous with Sabine, Glauco decides to tryout his new improved revolver by shooting his sleeping wife in the head three times, but not before turning on loud music and covering his beloved’s head with a couple of pillows. By the time Glauco is finished committing uxoricide, it is already daytime, so the novice wife killer gets dressed, rips up the latest designs he has created for work, picks up his suitcase, drives to the seaside, and dives into the water, but not before stripping off most his clothes and putting on a rather effeminate gold necklace. While in the water, Glauco spots a ship whose crew has just dropped the corpse of their cook into the sea. Glauco boards the ship and tells the blond Nordic captain that “The sea’s always been my dream” and begs to replace the cook. Glauco is told by the owner of the ship, a beauteous young woman, to go make her some chocolate mousse and then she takes his golden necklace and wears it. Glauco learns that the ship is headed to Tahiti and seems more excited than ever.

When describing the seemingly (and absurdly) happy ending of Dillinger Is Dead in a 1969 interview, auteur Marco Ferreri offered the following insights: “I certainly wanted the end to give a positive spin to the film as a whole. But this sort of ambiguity strikes me as less vivid and provocative than the ambiguity of my other films. It is essential to Dillinger, though, for it gives meaning to the whole. It is the film’s reason for being, in fact. The film, incidentally, is entirely ambiguous.” Personally, I interpreted the ending as the delusional childish fantasy of a deranged man who has lost all touch with reality and the fact that the film concludes with the entire screen turning blood red makes this seem all the more true. With Dillinger Is Dead, Ferreri more or less cinematically murdered the essence of the bourgeoisie in a work that depicts a respectable inventor who lives a lavish lifestyle, which includes a live-in mistress, yet throws everything away after ‘inheriting’ the gun and spirit of a proletarian gangster/killer like John Dillinger. The same year Dillinger Is Dead was released, underrated Italian auteur Salvatore Samperi (Nenè, Ernesto) directed a somewhat similarly themed yet more accessible work entitled Mother's Heart (1969) aka Cuore di mamma where a mute bourgeois mother decides to throw her life away by plotting with far-left terrorists to blow-up her ex-husband's factory. Additionally, a number of years before Ferreri’s film was released, Romano Scavolini directed the hidden gem of a film A mosca cieca (1966) aka The Blind Fly aka Ricordati di Haron—a work described by celebrated Italian fascist/futurist poet Giuseppe Ungaretti as a “masterpiece”—which follows a completely alienated young gentleman who discovers a revolver and decides to shoot a bunch of strangers, but not before pushing his girlfriend out of his life and contemplating suicide by shoving the gun in his mouth in a fashion that is not all that unlike the protagonist of Dillinger Is Dead. Indeed, while Ferreri’s film is often revered for being a revolutionary work that was created during a critical socio-political political climate, it certainly was not the first film to express such aesthetic and thematic idiosyncrasies, though it did do it in a manner that was nothing short of masterful and ultimately reached the mainstream, thus changing the way people perceived cinema during an imperative moment in history. In an interview, Ferreri would describe his film as virtually introducing the theme of “cinema as an anti-alienation weapon,” yet rather ironically, Dillinger Is Dead is one of the most notorious audience-alienating works of all time. An awkwardly foreboding work that falls in somewhere between cultivated celluloid torture, hermetic socio-politico-culture cinematic revolution, and entrancing absurdist black comedy, Dillinger Is Dead is a rare example of late-1960s experimental cinema that does not seem as worthless and outmoded as the “bobo” far-left politics that accompanied it. Set in a bourgeois world where images ranging from Italian Futurist paintings to photos of the Universal Horror icon The Wolf Man (which the antihero points his gun at) cover the wall, Dillinger Is Dead is a work that renounces both fascism and American capitalism as outmoded cultures, yet Ferreri would also demonstrate with his later films like The Future Is Woman (1984) aka Il futuro è donna that the politics of the new left had also degenerated into an outmoded memory. Indeed, Dillinger Is Dead reminded me how hopelessly the left failed in attempting to dream up a new and wonderful world but then again, Ferreri’s film ends in a manner that seems to reflect hell with its blood red tint.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 21, 2014

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.

I want to bugger Anita Pallenberg (as the bird was in 1962 when the bird was 18, not as the bird is now obviously).

ReplyDeleteI want to bugger Annie Girardot (as the bird was in 1949 when the bird was 18, not as the bird is now obviously, which is dead, unfortunately). The bird was like the Frog version of Ellen Page from the late 40`s and early 50`s, the cheeky little minx.

ReplyDeleteTy E, have you seen that new DVD edition of "The Brood" ?, i think its from that company called "Second Sight", on the back of the DVD is an incredible picture of Cindy Hinds (looking so much like Heather O`Rourke its unbelievable ! ! !). They know that the ONLY people who watch "The Brood" are geezers who want to have masturbatory fantasys about Cindy, the movie itself is nothing, its just all about Cindy. By the way, on the Blu-Ray theres an interveiw with Cindy, i wonder what the bird looks like now ?.

ReplyDeleteTy E, a good follow up reveiw here would be "Themroc" (1973), its on YouTube free of charge.

ReplyDeleteAs a Harlequin he looks like a faggot. By the way, the real star of this movie is John Dillinger.

ReplyDelete