Ironically, Zionism (which was described by Karl Kraus as a form of “Jewish anti-Semitism”) itself was born out of Jewish self-loathing, as its founder Theodor Herzl was originally a German nationalist (he was even a member of the German nationalist fraternity Burschenschaft, which many future Nazis, including Heinrich Himmler, were also members of) who started Zionism after realizing that Jews would never be accepted as real Germans among the indigenous German population and saw the movement as a way to make world Jewry strong (indeed, the early Zionists promoted eugenics and even collaborated with the Nazis during WWII). When director Henry Bean received the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival for The Believer, he stated during his acceptance speech for the film, “this is truly a story of love and hate. I love the provocative aspects…the notion of being a Jew and a Nazi at the same time.” Undoubtedly, in those couple sentences, Bean demonstrates the innate strangeness of being Jewish and being from a paradoxical religion where love and hate are not mutually exclusive because, as history demonstrates, Jews thrive on hatred (as Bean's film mentions, there would be no Israel without Auschwitz) for Hebrews would cease to exist without such hatred, thus making the Jewish neo-Nazi, in a bizarre way, the ultimate and most deeply devout Jew. Indeed, while being one of the most unwaveringly Jewish movies ever made, The Believer is also one of the most cleverly and eclectically anti-Semitic, as a work that puts Uncle Adolf's best-seller Mein Kampf to shame. That being said, Bean's film is more or less the contemporary celluloid equivalent to Otto Weininger's masterpiece Sex and Character (1903) aka Geschlecht und Charakter. Of course, it is surely a sign of our socially and morally inverted times when the most cleverly quasi-anti-Semitic film was directed by an actual Jew.

Thursday, May 29, 2014

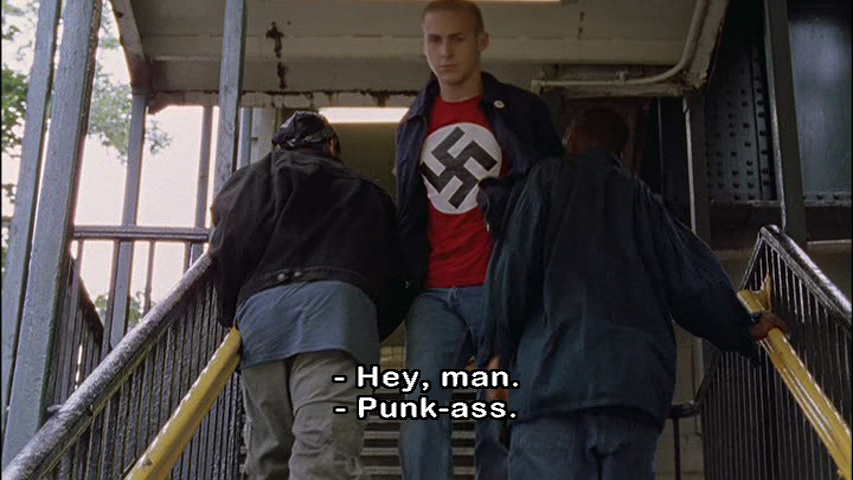

The Believer

In terms of the most damning films about Jews and Judaism, I believe it was not the National Socialists nor Islamists who were responsible for greatest and most provocative celluloid examinations of the Jewish question, but cinematic works penned and/or directed by the Jews themselves, with The Man in the Glass Booth (1975) directed by Arthur Hiller, Weininger's Last Night (1990) aka Weiningers Nacht directed by Paulus Manker, and Henry Bean’s The Believer (2001) being some of the most notable examples. What all of these films have in common aside from featuring great anti-Semitic rants is that all three works feature a self-loathing Jewish antihero with a split-personality who ultimately dies in the end as a result of circumstances relating to their diseased Hebraic mind. Undoubtedly, Bean’s The Believer is the freshest and most modern of these films, as a work that stars Hollywood heartthrob Ryan Gosling (Drive, The Place Beyond the Pines) during his pre-fame days in an insanely intense and totally unforgettable role as a Jewish neo-Nazi skinhead who finally loses control of his unhinged mind. Loosely based on the true story of Daniel "Dan" Burros—a former member and propagandist of Yankee Führer George Lincoln Rockwell’s American Nazi Party and, later, a recruiter for the KKK, who had a purported genius IQ of 154 and who committed suicide on October 31, 1965 by shooting himself in the chest and head while listening to Richard Wagner only an hour or so after an issue of The New York Times had been released that uncovered that he was 100% kosher. A rather conflicted fellow who supposedly derived great pleasure from drawing elaborate images of Jews being tortured yet at the same time would do curious things like bring Knish for his neo-Nazi friends to eat and would say things like “Let's eat this good Jew food!,” Burros was apparently heavily influenced by the neo-Spenglerian tome Imperium: The Philosophy of History and Politics (1948) written by Francis Parker Yockey (who is rumored to have been ¼ Jewish himself), which argued against the ‘racial materialism’ of the Third Reich and made the dubious claim that the 'spiritual' element of race was more important than the biological, hence why the work would appeal to a Jewish Nazi (incidentally, Leo Felton, a neo-Nazi criminal of both black and Jewish ancestry, was also influenced by the book). A sort of postmodern theological approach to Judaism written by two assimilated reform Jews, Henry Bean and Mark Jacobson, that exposes to the Goyim why it is not all that strange that a Jew might turn into a neo-Nazi, The Believer is like a thinking man’s take on American History X (1998) that is less about skinhead culture than a serious attempt to portray Judaism’s place in modern America in an age where true so-called ‘anti-Semitism’ has become an anachronism and where the religion itself has begun to lose meaning among its people, who typically consider themselves culturally kosher more than anything else. Once described by co-writer/director Henry Bean as being “embarrassingly philo-Semitic,” the film was nonetheless described by Rabbi Abraham Cooper of the Simon Wiesenthal Center as “a primer for anti-Semitism” and because of this, the The Believer was doomed to the deplorable fate of being released straight to cable TV, even thought it had won the Grand Jury Prize at the 2001 Sundance Film Festival and the Golden St. George at the 23rd Moscow International Film Festival. To the Rebbe’s credit, Bean’s work has more philosophical ammo against the Jews than the infamous Nazi propaganda film Der ewige Jude (1940) aka The Eternal Jew directed by Fritz Hippler (who was ironically 1/8 Jewish himself) and thus can seen as one of only a handful of films that will intrigue both rabid Zionist and National Socialists alike.

During the first couple minutes of The Believer, Jewish yeshiva student turned neo-Nazi skinhead Daniel Balint (Ryan Gosling) stalks a young Orthodox Jew wearing a yarmulke through a NYC subway and eventually smacks a book out of the young Yid’s hand, hands the book back to him, and then smacks and beats the shit out of the young bookish Heeb for not fighting back like a real man. Most interestingly, Mr. Balint begs the Jew to hit him back, stating, “Do me a favor…why don’t you fucking hit me, okay? Hit me. Hit me! Hit me, hit me, hit me. Fucking hit me. Hit me, please! You fucking kike!,” but the cowardly 'kike' naturally does nothing. Indeed, Daniel Balint hates the Jews due to their innate cowardliness and pacifism, as he associates Abraham’s obedience to God's command to kill/sacrifice his son Isaac in the Bible with the fact that most European Jews refused to fight back during the holocaust. As a young yeshiva student, Danny would argue with his teachers over scripture by interpreting it in a rather unorthodox way, but now as a neo-Nazi, he wants to kill Jews and believes he has found true comrades in the form of philistine skinheads who have no idea who Adolf Eichmann was. When Danny and his motley crew of skinhead dumb asses attend a small gathering hosted by intellectual fascists Curtis Zampf (Billy Zane) and Lina Moebius (Theresa Russell), he proposes randomly killing rich and successful Jews, including an investment banker/philanthropist named Ilio Manzetti (Henry Bean). Zampf considers Danny’s anti-Semitism and brute tactics outmoded, but Moebius , who “doesn’t care about the Jews one way or another,”sees a bright speaker and visionary in the young Jewish Nazi, as he reminds her of her ex-husband, who was a fascist revolutionary that went insane and now lives in a mental institution. Moebius’ daughter Carla (portrayed by ½ Jewess Summer Phoenix) also takes an interest in Danny and when he gets arrested the same night after getting in a brawl with some savage nig-nogs, she bails him out of jail and the two make somewhat violent sadomasochistic love (Carla is left with a bruise around her mouth). When Danny goes home, it is quite obvious that he resents the fact that his Father (Ronald Guttman) is a weak and sickly Jew. While at home, Danny gets a call from a journalist named Guy Danielsen (A. D. Miles), who flatters the kosher Nazi by telling him that he has heard that he has “interesting ideas” and that he wants to interview him. Unbeknownst to Danny, the journalist knows he is Jewish and his life as he knows it is about to change forever as a result.

When Danny meets journalist Guy Danielsen at a cafe, the postmodern Stormtrooper goes on a number of highly sophisticated and articulate anti-Jewish rants, including one in the spirit of self-loathing Austrian Jewish philosopher Otto Weininger where he argues that “the Jew is essentially female,” stating, “Real men—white, Christian men—we fuck a woman. We make her cum with our cocks. But the Jew doesn’t like to penetrate and thrust—he can’t assert himself that directly—so he resorts to perversion.” In his most impassioned speech, Danny makes his most damning attack against God’s chosen tribe most cherished geniuses, arguing: “Take the greatest Jewish minds ever—Marx, Freud, Einstein—what have they given us? Communism, infantile sexuality, and the atom bomb. In the mere three centuries it’s taken these people to emerge from the ghettos of Europe, they’ve ripped us out of a world of order and reason. They’re thrown us into a chaos of class warfare, irrational urges, relativity, into a world where the very existence of matter and meaning is in question. Why? ‘Cause it’s the deepest impulse of a Jewish soul to pull at the fabric of life till there’s nothing left but a thread. They want nothing but nothingness. Nothingness without end.” At this point, the journalist seems rather impressed, but he catches Danny off guard by asking him, “How can you believe this when you’re a Jew yourself?,” thus inciting the Hitlerite Hebrew to whip out a glock pistol and put it in pansy journalist Mr. Danielsen’s mouth while threatening to kill himself if the writer dares to print an article revealing his Judaic origins. Danny ends up going to a training camp setup by Zampf and Mobius with his skinhead comrades and during the first couple minutes upon arriving there, he beats up the biggest and most muscular neo-Nazi after he picks a fight with him, thus demonstrating he is far from an archetypical Jewish wimp. Danny also befriends a dorky explosives expert and a skilled marksman/possible fellow Jewish Nazi named Drake (Glenn Fitzgerald). Meanwhile, Danny attempts to rekindle his sexually violent relationship with Carla, but he soon realizes that Mr. Zampf is also carrying on an affair with her, even though he is in a relationship with her mother Lina Moebius. When Danny and his friends start a fight with the owners of a Jewish deli, they are sentenced to ‘sensitivity training’ by the courts where they must listen to the experience of holocaust survivors. When one elderly holocaust survivor tells a story about how his 3-year-old son was impaled with a bayonet right before his eyes by a German sergeant, Danny calls the man a “piece of shit” for not fighting back and protecting his son. Undoubtedly, the turning point for Danny comes when he and his friends wreck a synagogue and plant a bomb in the pulpit of the building. Danny’s racial/political schizophrenia becomes rather pronounced when he yells at his friends for messing up a Torah scroll, which is more or less the only holy object of Judaism. Danny decides to take the Torah, as well as a ‘tallit’ (a Jewish prayer shawl), back to the camp with him and comes to realize that being a Nazi alone is not fulfilling and that his Judaism has never left him. After learning the bomb that he planted at the synagogue malfunctioned (the timer stopped at 13 minutes, with the number 13 being a mystical number in Judaism), Danny begins repairing the torn Torah and even does fascist salutes while wearing the tallit and singing a Jewish prayer. When Drake asks Danny, “Do you wanna kill a Jew?,” the Judaic neo-Nazi reluctantly agrees. Drake reveals that he has already killed four Jews and when Danny asks him how he knew that his victims were Jewish, the marksman responds by stating, “I can tell. I was a Jew in a previous life.” Ultimately, Danny intentionally misses while attempting to assassinate the Jew Ilio Manzetti (the very same Jew he previously fantasized about killing) and Drake soon notices he is wearing the tallit, so a fight breaks out between the two, with the Jewish Nazi wounding his comrade, who later disappears.

When Danny arrives back in NYC, he is asked by Lina Moebius and Zampf to start fundraising for their fascist organization, which they hope will go mainstream, but the tough Hebraic National Socialist is so disgusted by the thought of doing such Jewish work as attempting to con companies out of their money (after all, he drives a forklift for a living) that he vomits, but Carla makes him feel better by licking the barf off his lips in a sick, if not highly sensual, fashion. Rather absurdly Danny begins teaching workshops on hating Jews during the day while teaching Carla, who is a dilettante of ancient languages, how to read the torah during the night. When Danny attempts to get funding from the head of a corporation, he is told, “Forget the Jewish stuff. It doesn’t play anymore. There’s only the market now, and it doesn’t care who you are.” Danny accuses the CEO of being a Jew and he replies somewhat strangely by stating, “Maybe I am. Maybe we’re all Jews now. What’s the difference?” Needless to say, Danny becomes disillusioned with the whole fascist movement and when he gives a speech arguing that anti-Semites should love Jews because it would cause the entire race to disappear into a sea of assimilation, Lina Moebius fires him from his job as a glorified fascist salesman of sorts. Meanwhile, Drake assassinates Ilio Manzetti and Danny is naturally blamed for the crime. Ultimately, Danny gets back in contact with his old classmates from the yeshiva school and decides to go out in a blaze of Christ-like glory. Danny convinces his friend Stuart (Dean Strober) to allow him to take his place reading from the torah at the bema on Yom Kippur. The night before he reads from the torah, Danny places a bomb in the pulpit of the synagogue. On the day of the big event, Danny notices Carla in the synagogue and forces her and everyone else out after telling his friend Stuart that there is a bomb in the building. Of course, Danny, as a suicidal Semite, refuses to leave and is blown up. In the last scene of the film during an ethereal mystical vision of sorts, Danny aimlessly ascends the stairs of the yeshiva school he once attended while being told by his old teacher that “There's nothing up there.” Indeed, in the end, Danny—the only really ‘believer’—learns that the Jewish (non)afterlife is truly “nothing but nothingness. Nothingness without end.”

In describing the real-life Jewish neo-Nazi Daniel Burros, The Believer director Henry Bean curiously stated, “He was a rabbi manque. Antisemitism is a form of practicing Judaism. He’s sort of a rabbi after all. A Jew by day, a Nazi by night. . . . He was desperately hiding something and compulsively trying to bring it out at the same time. People are drawn to contradiction. He undergoes a conversion, but not back to the Torah.” Bean, who is racially Jewish but never really seriously studied the religious aspects of his religion until working on the film, also confessed that by making a film about a Jewish neo-Nazi, he “began to understand what Judaism was.” Indeed, as The Believer demonstrates, unlike Christianity, Judaism is a self-critical religion about constantly questioning things, so it is only natural for a devout intelligent Jew to question the very religion itself, which protagonist Danny Balint did from the very beginning as depicted in his fights with teachers during his early yeshiva days. Although largely forgotten nowadays, some of the greatest intellectuals in the German-speaking world during the late-19th century/early-20th century where ‘self-loathing Jews,’ including the tragic philosopher Otto Weininger (who committed suicide at age 23 by shooting himself in the same room that Ludwig van Beethoven died in), philosopher/historian/actor/theater critic Egon Friedell, Austrian journalist/satirist Karl Kraus, and even one of the most important philosophers of his time, Ludwig Wittgenstein, who once wrote: “My thoughts are 100% Hebraic” and “Amongst Jews "genius" is found only in the holy man. Even the greatest of Jewish thinkers is no more than talented. (myself for instance.) I think there is some truth in my idea that I really only think reproductively.” Although Ryan Gosling seems far too Aryan in appearance and demeanor to portray a suicidal heeb, his performance in The Believer is nothing short of so amazingly visceral and fiercely impassioned that one almost comes to believe he is the real self-loathing Jew deal. While a discernibly low-budget work featuring a couple plot-holes and sometimes amateurish direction (it was Bean’s directorial debut, after all), The Believer is ultimately not only one of the most sophisticated films to ever deal with the Jewish question, but also a dark and primal examination of the Jewish collective unconscious that exposes an entire people in their most vulnerable and incriminating form. Indeed, for those that ever wondered why some people, including Jews, think Uncle Adolf may have had some Hebraic blood, The Believer is the film to see. Undoubtedly, the fact that a powerful rabbi managed to suppress the film and caused it to miss the mainstream attention it deserved just goes to show how important of a work The Believer is, especially in a post-European-dominated age where a largely Hebrew-run entity known as Hollywood is poisoning the world’s brains with its insipid high shekel filth, not to mention the fact that all of the wars in the middle east are a direct result of Zionist warmongering, among countless other contemporary kosher societal ills.

Ironically, Zionism (which was described by Karl Kraus as a form of “Jewish anti-Semitism”) itself was born out of Jewish self-loathing, as its founder Theodor Herzl was originally a German nationalist (he was even a member of the German nationalist fraternity Burschenschaft, which many future Nazis, including Heinrich Himmler, were also members of) who started Zionism after realizing that Jews would never be accepted as real Germans among the indigenous German population and saw the movement as a way to make world Jewry strong (indeed, the early Zionists promoted eugenics and even collaborated with the Nazis during WWII). When director Henry Bean received the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival for The Believer, he stated during his acceptance speech for the film, “this is truly a story of love and hate. I love the provocative aspects…the notion of being a Jew and a Nazi at the same time.” Undoubtedly, in those couple sentences, Bean demonstrates the innate strangeness of being Jewish and being from a paradoxical religion where love and hate are not mutually exclusive because, as history demonstrates, Jews thrive on hatred (as Bean's film mentions, there would be no Israel without Auschwitz) for Hebrews would cease to exist without such hatred, thus making the Jewish neo-Nazi, in a bizarre way, the ultimate and most deeply devout Jew. Indeed, while being one of the most unwaveringly Jewish movies ever made, The Believer is also one of the most cleverly and eclectically anti-Semitic, as a work that puts Uncle Adolf's best-seller Mein Kampf to shame. That being said, Bean's film is more or less the contemporary celluloid equivalent to Otto Weininger's masterpiece Sex and Character (1903) aka Geschlecht und Charakter. Of course, it is surely a sign of our socially and morally inverted times when the most cleverly quasi-anti-Semitic film was directed by an actual Jew.

Ironically, Zionism (which was described by Karl Kraus as a form of “Jewish anti-Semitism”) itself was born out of Jewish self-loathing, as its founder Theodor Herzl was originally a German nationalist (he was even a member of the German nationalist fraternity Burschenschaft, which many future Nazis, including Heinrich Himmler, were also members of) who started Zionism after realizing that Jews would never be accepted as real Germans among the indigenous German population and saw the movement as a way to make world Jewry strong (indeed, the early Zionists promoted eugenics and even collaborated with the Nazis during WWII). When director Henry Bean received the Grand Jury Prize at the Sundance Film Festival for The Believer, he stated during his acceptance speech for the film, “this is truly a story of love and hate. I love the provocative aspects…the notion of being a Jew and a Nazi at the same time.” Undoubtedly, in those couple sentences, Bean demonstrates the innate strangeness of being Jewish and being from a paradoxical religion where love and hate are not mutually exclusive because, as history demonstrates, Jews thrive on hatred (as Bean's film mentions, there would be no Israel without Auschwitz) for Hebrews would cease to exist without such hatred, thus making the Jewish neo-Nazi, in a bizarre way, the ultimate and most deeply devout Jew. Indeed, while being one of the most unwaveringly Jewish movies ever made, The Believer is also one of the most cleverly and eclectically anti-Semitic, as a work that puts Uncle Adolf's best-seller Mein Kampf to shame. That being said, Bean's film is more or less the contemporary celluloid equivalent to Otto Weininger's masterpiece Sex and Character (1903) aka Geschlecht und Charakter. Of course, it is surely a sign of our socially and morally inverted times when the most cleverly quasi-anti-Semitic film was directed by an actual Jew.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 29, 2014

10

comments

![]()

Laurin

While the Germans have had quite arguably a greater impact on horror cinema than any other nation in the world, by the time of the Nazi era, the Teutons had more or less completely abandoned the genre. Indeed, aside from Niklaus Schilling’s Nachtschatten (1972) aka Nightshade and Ulli Lommel’s Die Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe (1973) aka The Tenderness of Wolves and Werner Herzog’s Nosferatu the Vampyre (1979), German New Cinema—the greatest and most important German film movement of the post-WWII era—did not really produce any notable horror films. As conservative auteur Hans-Jürgen Syberberg argued in his magnum opus Hitler: A Film from Germany (1977), post-WWII Germans felt the need to dispose of their national myths as their nation’s entire kultur had been supposedly tainted by Uncle Adolf and his merry men, hence the obsession with far-left politics, revolutionary terrorism, feminism, and other cultural ills among filmmakers associated with German New Cinema. After all, one cannot forget that the greatest Aryan horror novelist of the early 20th century, Hanns Heinz Ewers—a remarkable satanic Renaissance man of sorts who was one of the first people to recognize film as a legitimate artistic medium, penned the screenplay for the first independent film in cinema history, The Student of Prague (1913), and whose 1911 masterpiece horror novel Alraune was cinematically adapted no less than five times (not to mention the fact that the Hollywood Species films are a reworking of Alraune)—was a National Socialist party member and wrote a biographical novel on Nazi martyr Horst Wessel, which was later adapted into the early NS propaganda film Hans Westmar (1933). Luckily, a handful of German filmmakers like Jörg Buttgereit (Nekromantik, Der Todesking) and Robert Sigl (Schrei - denn ich werde dich töten! aka School’s Out, Hepzibah - Sie holt dich im Schlaf aka The Village) decided to create their own new myths in the Teutonic tradition of mystifying angst, with the latter’s work Laurin (1989) aka Laurin: A Journey Into Death being arguably one of the greatest and most underrated films of German film history as a visually exquisite cross-genre work with an intricate and labyrinthine plot that is depicted from the innocent perspective of a little girl.

Of course, as a Gothic fairytale-like period piece set in an exotic location (despite ostensibly set in a 19th century German seaside village, the film was actually shot in Hungary) that is like the Czech arthouse vampire fantasy masterpiece Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (1970) aka Valerie a týden divů meets Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s Effi Briest (1974) meets Lucio Fulci’s unconventional giallo Don't Torture a Duckling (1972), Laurin is not your typical horror film, as a work of nearly perfectly paced celluloid elegance of the timeless sort that does not wallow in contemporary postmodern diseases like irony, cynicism, or parody. Indeed, one would never suspect that auteur Robert Sigl was only 25-years-old when he started production on the film, which ultimately earned him the Bavarian Film Award in 1989 for ‘Best New Director,’ thus becoming the youngest filmmaker to ever earn the coveted prize (he was also nominated for the Max-Ophüls-Award the same year). Directed by a man who once stated, “I hate the Christian church and especially the Pope,” Laurin may be rather traditional in terms of aesthetic style and storytelling, but the work has unflinching anti-Christian and even homoerotic undertones despite being a sensitively assembled film where the protagonist is a little girl. Indeed, like Richard Blackburn’s lesbian-themed Lovecraftian vampire flick Lemora: A Child's Tale of the Supernatural (1973) and Philip Ridley’s 1950s-set rural American bloodsucker work The Reflecting Skin (1990), Laurin is a decidedly dark and sexually disturbing neo-fairytale where a child is forced to grow up due to horrifying circumstances that have entered her life relating to death and perversion. Shot in a rural area of Hungary that apparently had not changed in over a hundred years with a mostly all-Hungarian cast, Laurin is an otherworldly Teutonic- Magyar celluloid Nachtmahr of great beauty and cultivated brutality where the hinterlands become a place of mystifying horrors and secretive sexual savagery.

Little Laurin (Dóra Szinetár) is watching her seafarer father Arne (János Derzsi) grab her beauteous mother Flora Anderson’s (Brigitte Karner) bosoms from her crib. Not surprisingly, Laurin’s grandmother Olga (Hédi Temessy) yells at her son Arne for manhandling his wife in front of their daughter. Of course, the little girl does not mind because she can tell her parents are deeply in love. As a man who is constantly away due to his job, Arne is about to head to the sea once again, but he does not realize that this will be the last time he sees his wife. Before Arne leaves, Flora reveals to him that she is pregnant, which brings the seafarer great joy. Though Arne promises his wife that, “Someday, I will take you along and we’ll sail down the river and out into the deep blue sea,” fate has different and rather unfortunate plans for the two true lovers. Indeed, not long after seeing her husband off as he sails away to god knows where, Flora spots a man fiddling with the corpse of a young gypsy boy. Incidentally, the same gypsy boy banged on little Laurin’s window for help only minutes before, but she was too scared to answer the scared little boy's pleas for help. The next day, a peasant man finds Flora’s corpse floating in the water next to the bridge, with a jewelry box that the dead woman's husband had given her shimmering through the water from the bottom of the lake. Grandmother Olga is so angered by Flora’s dubious death that she damns god, but little does she realize that one of god's servants' progeny was involved with her daughter-in-law's tragic death. When Laurin goes to look at her mother's corpse at night, she notices a tear trickling down her cold postmortem progenitor's pale yet strangely beautiful cheek. Grandmother Olga attempts to setup Arne with a hot redheaded single mother named Frau Greta Berghaus (Kati Sír) who has a little boy named Stefan (Barnabás Tóth) that Laurin is friends with, but the stoic seafarer refuses to remarry as he still loves Flora. Naturally, Arne eventually goes back to the sea and once again leaves his daughter Laurin and mother Olga helpless.

Around the same time Arne leaves, his virtual doppelganger arrives. Indeed, Laurin mistakes the local Pastor’s (Endre Kátay) son Van Rees (Károly Eperjes) for her own father when he arrives on ship. Van Rees is a secretive and seemingly impenetrable man with a somewhat flat affect who becomes Laurin and Stefan’s schoolteacher and he seems to develop a special interest in both of them for varying reasons. When Stefan is bullied in class by a couple boys, his mother Greta invites the teacher over for dinner, but on Van Rees' arrival at the house, he overhears the young mother talking with his Pastor father. It turns out that the Pastor has been carrying on an affair with Greta Berghaus and Stefan is his bastard son, thus making him Van Rees’ half-brother. Van Rees’ mother died when he was just a boy and his Pastor father, who never got over the death of his wife, abused his son during his childhood, hence his disdain for religion and rather peculiar relationship with both his father and young children. While the Pastor is such a puritanical man that he refuses to have mirrors in house because they are purportedly “instruments of human vanity,” that does not stop him from screwing a young woman that, in terms of age, could be his daughter. Eventually, Stefan disappears and Laurin goes looking for her friend, which eventually leads her to theorizing that Van Rees is involved as she finds her missing friend's glasses in the mouth of an evil-looking black wolfdog owned by the Van Rees family. Indeed, in an earlier and rather disturbing scene in the film, Van Rees crudely gazes at his ½ bastard brother Stefan’s naked body from an outdoor window, as if turned on by the little lad. Eventually, Laurin finds a secret door in the floor at some ruins near the local church that leads to a purgatory-like basement ‘sex dungeon’ of sorts where Van Rees takes his little boys. While Van Rees eventually finds Laurin hiding in a closet and states to her in a somewhat sinister fashion, “I don’t like having little girls spy on me,” the little girl manages to escape his limp-wrist pansy grasp. Of course, knowing that the little girl is aware that he is a pernicious pedophile serial killer, Van Rees stalks Laurin all the way back to her house and intends to kill her slasher-style with a knife. Through a dream-sequence, it is revealed that Laurin’s mother actually died by accident after falling off the bridge while attempting to escape from Van Rees upon spotting him carrying the dead gypsy boy. To scare Van Rees, Laurin has the bright idea to wear her dead mother’s cloak, thus tricking the killer into thinking he is seeing a ghost of the women whose death he inadvertently caused. Indeed, Van Rees panics upon seeing Laurin dressed in the ghostly cloak, thereupon causing him to fall backwards down some stairs and eventually die in a freak accident after a large nail sticking in the wall enters the back of his skull and penetrates his diseased brain. After Van Rees dies, blood trickles from his eyes as if he is weeping as a result of his miserable childhood and in sympathy for all the children he has killed. As for Laurin, she feels empowered by wearing her belated mother's cloak, especially after using it to kill her mother's killer.

Interestingly, apparently director Robert Sigl received an exceedingly negative response from both students and professors while attending Munich Film Academy due to the homoerotic and even incestuous nature of his films, with his 20-minute short Der Weihnachtsbaum (1983) aka The Christmas Tree being deemed especially offensive due to its supposed depiction of pathological sadomasochistic relationship between a father and son. In an interview with the director featured in the book Caligari's Heirs: The German Cinema of Fear after 1945 (2006), Sigl stated regarding his less than ideal experience at film school and his decisive desire to change his style for his first feature so as to make it more accessible to a more general audience: “I guess some people felt personally offended because of the psychosexual symbolism and theme. In LAURIN, I packaged all this by phrasing it in the psychosexual terms of a fairy tale by the Brothers Grimm, which made it more palatable to a broader audience. This way, it's more subliminal. Because I do want to reach a lot of people, even entertain them. But that doesn't matter much in one's first efforts as a filmmaker; they're usually more about refining one's style anyway. As a matter of fact, an idiosyncratic style doesn't seem to be much in demand these days. Someone like Polanski, Lynch, or Cronenberg would have a hard time if they were starting out today.” Indeed, Laurin is like the Brothers Grimm meets Leopold and Loeb as set in a living Caspar David Friedrich painting, which makes for a shockingly aesthetically fruitful combo that can be appreciated by both adults and children alike. While Sigl’s first feature Laurin was a hit upon its release and went on to develop an international cult following of sorts, the director has yet to direct anything else nearly as interesting, as if he was perennially jinxed by the greatness of his debut film. Aside from a couple TV movies, including the Scream rip-off Schrei - denn ich werde dich töten! (1999) aka School’s Out, which was distributed in the U.S. by Fangoria, Sigl has mainly spent most of career directing miniseries, including the Twin Peaks-esque Stella Stellaris (1993), as well as episodes of popular German TV series like Lexx (1997-2002) and Tatort (1969–current). Apparently, the last episode of Tatort that Sigl directed caused much controversy in Deutschland, as it featured an incestuous sex scene. Why Sigl decided to abandon the glorious path he created with his masterpiece Laurin and went on to direct less mature works is questionable, but at least the director demonstrated for a moment during the late-1980s that somewhere deep down in the German collective unconscious lays the dark legacy of the Brothers Grimm. Sort of like an (anti)Heimat take on Fritz Lang’s masterpiece M (1931) in its depiction of a pathetic and mentally peturbed pedophile serial killer, Laurin is undoubtedly one of the sickest celluloid fairytales ever made as a work depicting a man lusting over and assumedly killing his own prepubescent ½ brother, yet Sigl directed the film in such a carefully cultivated, nuanced, and poetic fashion that it never seems like cheap horror trash, thus reminding the viewer why Germany is the same nation that produced H.H. Ewers and F.W. Murnau.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 29, 2014

18

comments

![]()

Wednesday, May 28, 2014

Under the Pavement Lies the Strand

To me, there are few things more repugnant in the cinematic realm than feminist filmmakers, as they actively debase the artistic medium of film and seem to think that spreading some sort of innately incoherent and rarely concrete message about ‘female power’ is all that one needs to do to make a film, as if aesthetics and entertainment value are totally insignificant matters that are, at best, of secondary importance. One of the few self-professed feminist filmmakers that I actually I have a degree of respect for is German auteur Helma Sanders-Brahms who, despite being a feminist, was not afraid to direct films about quasi-fascist poets (i.e. Heinrich, My Heart is Mine Alone aka Mein Herz – niemandem!) and even went so far as to defend her cinematic mother-figure Leni Riefenstahl by lauding her work Tiefland (1954) as an anti-Hitler allegory of sorts and rhetorically asking regarding the film: “How is it possible that after fifty years the fear of dealing with this film is still so great that just the refusal to view it is considered a correct attitude for German intellectuals?” With Sanders-Brahms’ rather recent death on May 27, 2014, I decided it was about time that I watch her first feature Under the Pavement Lies the Strand (1975) aka Unter dem Pflaster ist der Strand aka Under the Beach's Cobbles aka Beach under the Sidewalk starring Grischa Huber (The Serpent’s Egg, Malou) and Heinrich Giskes (Heinrich, Bang Boom Bang - Ein todsicheres Ding). Created when Sanders-Brahms was totally unknown and had yet to have any meaningful involvement with any sort of feminist movement, Under the Pavement Lies the Strand is a black-and-white low-budget avant-garde work that went on to became “a cult film in the German feminist movement” and rightfully earned its lead Grischa Huber the the Deutscher Filmpreis (Filmband in Gold) at the 1975 German Film Awards. A melancholy work about two stage actors/left-wing activists who were involved with the German “68er-Bewegung” student movement yet have now become somewhat disillusioned with the cause and further find their ideals tested when the female protagonist becomes pregnant amidst a new abortion law in West Germany that they had previously actively protested, Under the Pavement Lies the Strand is a thoughtful and relatively nuanced work that ultimately asks more questions than it answers, thus making it quite different from the idiotically idealistic philo-Semitic/man-hating Hollywoodized agitprop pieces of Margarethe von Trotta and the aesthetically sterile celluloid manifestos of Helke Sander. Indeed, like her Austrian celluloid compatriot Valie Export (Unsichtbare Gegner aka Invisible Adversaries, Menschenfrauen), Sanders-Brahms clearly took cinema serious as an art form and demonstrated with Under the Pavement Lies the Strand she had a keen talent for assembling a realistic modern romance film set during a degenerate zeitgeist when young men and women were increasingly confused about their place in German society.

Grischa (Grischa Huber) and Heinrich (Heinrich Giskes) are stage actors involved in a feminist reworking of a Greek tragedy that is being shot for German television (indeed, during this time, filming theatre for TV was not uncommon in Germany, with Fassbinder directing no less than four of these TV plays). As the narrator (Helma Sanders-Brahms) states of a scene featuring an eclectic group of female actresses: “These actresses act out the rule of women, as it was thousands of years ago, and its abolition ordained by men.” Like all the actresses, Grischa rehearses for the play during the the day and thinks of her ‘role as a woman’ during the night, but that is about to change when genuine human feeling gets in the way of cold and abstract political idealism. During one of these nights, Heinrich, who is wearing nothing but a cock-shaped codpiece and has brought his two dogs along with him, visits Grischa in her dressing room after practicing for a play. Assumedly rainwashed by pinko-hippie ideas of communal living, Grischa complains to Heinrich, “I’d like to see an end of the separation of private life and job. What I do on the stage is what I need, you see. What I say comes from deep within me, and, of course, it comes out stronger on stage.” Ultimately, the two get locked in the building and after Heinrich describes to Grischa how she resembles his dead sister who was murdered (he was 4 and she was 15 at the time, thus hinting she was murdered during the Second World War), so naturally they make love. As Grischa states of Heinrich and their relationship: “In Heinrich’s mind always the hope…that remained unfulfilled with the many…because they were too few and not tenacious enough; hope of fulfillment with one person, taking up the struggle, with love a revolution for two.” Indeed, Heinrich complains about how everyone was united in 1968 during the time of the student movement protests, but now everyone has splintered off into smaller groups, which has created a sort of rivalry amongst former comrades. It seems Heinrich has finally grown up and realizes having a family is more important than any sort of abstract political idealism, telling Grischa, “I will give you a baby,” though he seems somewhat immature in other regards, as he cannot stand it when his girlfriend does not give him 100% of her attention and acts out as a result. Of course, being more concerned with her acting career and political activism and resenting more than anything the idea of living a “domesticate life” as a housewife with children, as if that is somehow beneath her, Grischa tells Heinrich more than one time that she does not want to have a child. Obsessed with feminist ideas that she has clearly been brainwashed with, Grischa begins actively interviewing proletarian factory workers about motherhood and abortions, as if she has been contracted by some feminist think-tank to carry out a study. Virtually every woman that the actress ends up interviewing confesses to having had an abortion at some point in their life as a result of necessity and none of them seem particularly proud of it, though they have no problem stating these things in front of their children.

Meanwhile, ‘Heini’ (as Grischa affectionately calls him) begins getting all moody and broody about his girlfriend’s refusal to pregnant, so he mopes around his apartment while reading Friedrich Engels’ The Origin of the Family, Private Property, and the State (1884)—a work that absurdly argues that the proletariat is free from ‘moral decay’ (i.e. prostitution, extramarital affairs, etc.) because they lack the monetary means to have a inheritance-based bourgeois marriage, which forces people to marry for monetary reasons and not out of love, thus causing them to seek prostitutes—as if such an outmoded feminist communist text will provide him with inspiration for being a husband and father. Heini is also a fan of the Persian fairytale Majnun Layla aka Lelia and Madschnun, which he describes as having essentially the same message as Engels’ work. Fed up with Grischa’s seemingly pathological activism (at one point, he asks her: “Why not let me rot?”), Heinrich begins hanging out with a cute blonde chick and complains to her about he is tired of “play acting,” adding: “I’m not so stuck on politics. I think it’s arrogant for an actor to go and tell workers what it’s all about. I’d like a kind of folk theatre, something like I’ve seen the French doing. Like “Théâtre du Soleil.” […] something people get a kick out of.” When Grischa calls Heini and states, “I understand you wanting your freedom. I want mine, too. But you won’t be freer by being alone. It’s something different. You just have…to discover a new way of life, right? I know I’ve made mistakes but we can change that. If we separate for a few days, it’ll be all right perhaps,” he says nothing, even though she begs him to. Since Grischa has just recently stopped taking birth control after 7 years of continuously using them after hearing they cause sterilization, she naturally ends up getting pregnant, but she is too afraid to tell Heini, so she attempts to get the courage to do so by practicing what she plans to say to her boyfriend and recording it on her tape-recorder (which, is ironically the same tape-recorder she uses to interview prole women about abortions). Eventually, Grischa goes to a feminist rally to look for a feminist gynecologist named Dr. Siebert and while she is there she hears a bunch of hilariously deluded feminist folk musicians singing the following loony lyrics: “We are women and we fight fearlessly for the revolution…With all comrades for communism…United in struggle we are strong.” When Grischa finally finds Dr. Siebert, she complains about her worries regarding her pregnancy and asks whether or not she should keep the baby due to her dubious relationship with Heinrich and her concerns about the future of her career. Grischa also complains about how Heinrich suffers a “mother complex” and has no realistic means to become a father. Ultimately, Dr. Siebert gives Grischa advice on how to get an abortion, recommending that she fake being suicidal if she wants a legal abortion. After talking to the gynecologist, Grischa goes by Heinrich’s apartment and attempts to reconcile with him, but he complains to his girlfriend that, “You’re too strong for me” and claims he has an incapacity for tenderness because, “I was brought up by Nazis, I’m a fascist. I have visions of beating you to a pulp.” In the end, Heinrich says he would rather screw his dog than Grischa and even threatens suicide, though the two seem to more or less reconcile, though the future of their relationship seems dubious at best.

As German novelist Peter Schneider, who was a spokesman for the German student movement, noted regarding his generation and the failure of 68er-Bewegung movement to achieve anything of value: “It is now clear…that the protestors were terribly naïve and unself-conscious in their anti-fascism. There has probably never been a movement at once so obsessed with language and so incapable of articulating its ideas and desires.” Indeed, the protagonists of Sanders-Brahms’ Under the Pavement Lies the Strand certainly seem like they have no clue what they are doing, as if their political activism is merely a truly reactionary response to some sort of inner void, as well as a nonsensical means to atone for the supposed sins of their parents’ generation, with Heinrich’s remark, “I was brought up by Nazis, I’m a fascist,” completely highlighting this hysterical post-Hitler/post-holocaust phenomenon of collective guilt and ethno-masochism. Of course, instead of evolving into morally pristine humanist heroes, these student activists essentially became perennial children who denied themselves of adulthood and maturity, with their activism being a mere pathetic substitute for a real life that involves marriage, children, and a fruitful career. As Sanders-Brahms would demonstrate with her most popular film, Germany, Pale Mother (1980) aka Deutschland, bleiche Mutter, which is highly autobiographical in nature (the director even cast her own daughter to player herself as a baby), she seemed to have not completely forgiven her father for how he treated her mother, hence the director's unsurprising adoption of a feminism Weltanschauung. Ironically, at the same time, as Under the Pavement Lies the Strand, as well as Heinrich, Germany, Pale Mother, My Heart is Mine Alone, and Geliebte Clara (2008) aka Beloved Clara demonstrate, Sanders-Brahms seemed to have a strange empathy and attraction to weak and mentally disturbed men, so I would argue that her feminism was less a result of feminist brainwashing than her natural reaction to being a truly strong and independent woman who was attracted to weak men, hence her respect for Riefenstahl (who, when she was 60 years old, started a lifelong romance with her cameraman Horst Kettner, who was 40 years her junior!). Indeed, very rarely do women make good filmmakers and the only thing most women have to do to get critical appraisal is simply directing a film, no matter how horrendous it is, and they will touted around as geniuses and the most important voices of their generation. While one can argue that most of Sanders-Brahms’ work has some feminist themes, she never followed any sort of artistically-stifling misandrist dogma and was not afraid to branch out by making period pieces about gay proto-fascist poets and rather dark semi-surreal work like No Mercy, No Future that somewhat grotesquely depicts literal and figurative schizophrenia in post-WWII Berlin. Although the director’s first and most innately feminist-themed work, Under the Pavement Lies the Strand proves that Sanders-Brahms was first and foremost a serious filmmaker who had a rather idiosyncratic obsession with idiosyncratic men who seemed less masculine-minded than she was. Indeed, when the great Austrian philosopher Otto Weininger wrote in his masterpiece Sex and Character (1903) aka Geschlecht und Charakter that there was a small percentage of the female population that had what it took to be truly emancipated in society despite their gender, he was speaking of women like Helma Sanders-Brahms. Arguably the greatest ‘Trauerarbeit’ (aka “working of mourning”) film ever made about the Teutonic student movement of 1968, Under the Pavement Lies the Strand reveals in an understated and totally serious fashion that melancholy did not die with the Hitler generation, but was passed on to the subsequent generation, who quite arguably found it harder to cope with German history than their parents who had actually lived through it.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 28, 2014

3

comments

![]()

Tuesday, May 27, 2014

Mrs. Meitlemeihr

Probably no other contemporary actor has portrayed Adolf Hitler and various other Nazi leaders more times, at least in such a stoically campy fashion, than unambiguously gay German character actor Udo Kier (Blood for Dracula, Nárcisz és Psyché), with his role as a sort of scatological ‘Asshole Shitler’ in Christoph Schlingensief’s spastic satire 100 Jahre Adolf Hitler - Die letzte Stunde im Führerbunker (1989) aka 100 Jahre Adolf Hitler - Die letzte Stunde im Führerbunker being one of the most devastatingly deranged depictions of the Führer in all of cinema history. While Schlingensief’s Hitler flick is not exactly well known, it is certainly better known the 29-minute British dark comedy short Mrs. Meitlemeihr (2002) directed and co-written by successful advert man turned would-be-filmmaker Graham Rose, co-penned by English actor Jeff Rawle (Billy Liar, Drop the Dead Donkey) and starring Herr Kier as Big H in old hag drag. Indeed, a work of degenerate historical fantasy, Graham’s film depicts a decidedly desperate Hitler disguised as a woman and hiding out in late-1940s rubble-ridden London amongst assorted human rabble. Needless to say, Mrs. Meitlemeihr is in the timeless British tradition of being resentful regarding the Second World War and thus features a one-dimensional depiction of Hitler as an intolerable and intolerant raving buffoon, albeit this time wearing a granny wig and dress. Undoubtedly, the big twist of the film is that a perverted old Jewish widow becomes obsessed with attempting to get inside Hitler’s granny panties, not realizing that he is trying to fuck the great Führer himself. Keeping that dubious and easy-to-botch premise in mind, it is easy to see why Mrs. Meitlemeihr, which was originally intended as demo piece to entice prospective investors for a bigger and more elaborate production, was never made into a full-length feature film as was originally planned by Mr. Rose. If there is any group that hates Hitler and the Germans more than the Jews, it is indubitably the Brits, and with good reason. While the Jews at least got their first official nation in thousands of years out of the holocaust, the Second World War not only cost the Brits their empire and domination of the world, but also their pride and dignity. As revealed in the great German documentary The Fine Art of Separating People from Their Money (1998) directed by Hermann Vaske and hosted by Dennis Hopper, like the Jews, the Brits adopted comedy as a way to relieve their pain and naturally Uncle Adolf became the incessant butt of the jokes for countless hack England comedians and has remained so for no less than over half a century. With the somewhat recent taboloid rumor that Hitler went into hiding after the Second World War, died in South America in 1984 at the age of 95, and even had a negress girlfriend, I felt a little bit eager about watching a film as seemingly as stupid and insipid regarding the National Socialist leader's imaginary post-WWII years and Mrs. Meitlemeihr certainly fit the bill as a work that also once again demonstrates that the English have an unhealthy obsession with men wearing dresses.

It is April 1945 and Adolf Hitler (Udo Kier) has decided to opt out on his part of his suicide pact with his long-term companion Eva Braun (Tara Ward), who he married only less than 40 hours before she put a bullet in her brain. Indeed, bloated bastard Martin Bormann (Hendrik Arnst) has a transport ready for Hitler to escape to Argentina, as they plan to start building a Fourth Reich from scratch once they get settled in their new adopted homeland. To fake big H’s death, a SS man shoots a nerdy man that vaguely resembles the Führer in the head and uses his corpse as a body double for the Allies to find. Flash forward to November 1947 and somehow Uncle Adolf did not make it to scenic Argentina, as he is now stuck in an impoverished white ghetto in London, even complaining in a letter to his boy Bormann: “My struggle to exist here is becoming intolerable. Still no papers! Every day I wait, but nothing. Since our last communication, the money is all but gone. I’m starving. And have been reduced to filth and squalor. How much longer must I endure this humiliation? This room where I must remain prisoner is a living nightmare. I fear, above all, that my identity will be revealed. I dare not venture out, but I must! My health is deteriorating by the day. You’re my only hope and salvation. In the name of the Fatherland, I beg of you, Bormann…Communicate!” The fallen Führer is so poor that he does not even have a stamp to send the letter, so he has to go to the post office to buy one with what little money he has left. To hide his identity, Hitler decides to dress in drag and use the alias Mrs. Meitlemeihr. Unfortunately for Adolf, there is an exceedingly annoying Jewish widow that lives in London that has a thing for somewhat masculine Fräuleins.

On the way to the post office, some rotten little sub-literate Brit boys playing with a rugged dummy with a Hitler mask make the mistake of begging Hitler for money, but the cross-dressing Wagnerian Übermensch is not amused by the lads’ crude cardboard caricature of him, so he states in German, “What insolence. You ought to be locked up.” When Hitler finally gets to the post-office, the elderly clerk, who is hard at hearing, has a very hard time understanding what the lapsed Nazi messiah is saying, so he states under his breath, “I hate zee handicapped.” After leaving the post office, Hitler is followed by a Jewish widow named Lenny Veldermann (John Levitt) who, for whatever reason, is rather attracted to the world’s most infamous anti-Semite. It turns out that Lenny—a stereotypically sleazy, pushy, and wisecracking Hebrew—lives in the same dilapidated apartment building as Uncle Adolf. Needless to say, Lenny invites himself over to Hitler’s apartment for dinner without actually getting permission, as he hopes to get lucky with Herr Hitler. While Hitler complains, “I’ve been betrayed…forgotten. FORGOTTEN! Hated!,” during the dinner, the Jew self-righteously states that the Germans must “accept their guilt” for the holocaust. Needless to say, Hitler becomes infuriated and hatefully shouts, “The Germans will rise again” and then states in German, “The German spirit…will be the world’s salvation.” When the two men get drunk and Hitler passes out, Veldermann attempts to take advantage of the unconscious Führer, but when the Jew reaches up his dress to cop a feel, he screams “a cock” and a brawl breaks out between the two born adversaries. After strangling the Jew and stating “Jewish bastard pig,” Hitler has a bottle smashed over his head and some sort of broom shoved up his rectum. In an act of would-be-poetic-justice, the Jew attempts to gas Hitler by shoving his head in a gas oven, but the two men pass out before the final solution can be fully carried out. The next day, Veldermann realizes that Mrs. Meitlemeihr is actually Hitler after noticing a stain of dried blood covering Uncle Adolf’s upper lip that resembles the great dictator's iconic Charlie Chaplin mustache. After the Jew goes back to his room, a postal worker attempts to deliver a letter to Hitler from Martin Bormann and presses extra hard on the door bell to get the mysterious tenant's attention, thus causing the entire apartment to blow up in the process after a spark from the poorly wired door bell ignites the gas from the stove that filled up the apartment the previous during the sissy Aryan versus Hebrew slapstick brawl. Indeed, in the end, Adolf Hitler ironically dies in a literal holocaust.

Undoubtedly, in terms of subversive British Hitler humor, Mrs. Meitlemeihr is nothing new. On top of the never released black comedy Son of Hitler (1978) starring Bud Cort as the eponymous lead and Peter Cushing as a neo-nazi leader, the short-lived British sitcom Heil Honey I'm Home! (1990) portrayed Hitler and Eva Braun living next door to a Judaic couple named the Goldensteins. Of course, Heil Honey I'm Home! was cancelled after the first episode, so it should be no surprise that Mrs. Meitlemeihr never developed into the extravagant feature film that director Graham Rose intended it to be. While I was not exactly impressed with the short, I must give props to Mr. Rose for siring such a preposterous film that is, if nothing else, in rather poor taste and would probably offend the likes of overrated kosher comedian Mel Brooks, who practically made a living off of poking fun at Hitler and the Nazis. Interestingly, it is revealed in the British documentary Hitler: The Comedy Years (2007) directed by Jacques Peretti—a work that goes into rather deplorable detail about why Uncle Adolf has become a mainstay of British comedy for over the past half-century or so—that McEnglish comedian Spike Milligan was obsessed with Hitler in such an unhealthy and all-consuming fashion that he suffered a mental breakdown in Italy and had to be hospitalized for a while. Without question, Mrs. Meitlemeihr also demonstrates this sort of post-WWII Hitler-mania, as another one of the countless examples as to why the British seem to suffer from sort of mass reverse Hitlerite psychosis. Unquestionably, the film’s greatest strength is star Udo Kier’s typically over-the-top camp-addled performance, thus making the film a somewhat worthwhile endeavor for fans of the queer kraut character actor. Of course, as a man who used to dress in drag while working as a transvestite prostitute (with his bud R.W. Fassbinder being his pimp!) during his pre-acting career years, Kier probably did not have to put much effort into his role for Mrs. Meitlemeihr. It should also be noted that Kier's very first acting role was in the British short film Road to Saint Tropez (1966) directed by English actor/auteur Michael Sarne (Joanna, Myra Breckinridge). More recently, Kier played a small role as a futuristic Führer in the patently pathetically politically correct multiculturalist sci-fi-comedy Iron Sky (2012). Of course a film featuring a cross-dressing Hitler being quasi-date-raped by a rather repugnant Hebrew is easier to digest than a cowardly miscegenation-saluting agitprop piece of celluloid scheiß like Iron Sky where a blonde Nordic Nazi babe ends up falling in love with an American negro astronaut. One must also give credit to Mrs. Meitlemeihr for not concluding with a sickeningly sentimental and conspicuously cliche quasi-commie speech about the need for tolerance like Chaplin's The Great Dictator (1940). Apparently, Hitler, who was a cinephile of sorts, viewed Chaplin's film no less than two times, but no one actually knows what the Führer thought of the film. Personally, I would be me interested to know what Hitler would think of thought of Mrs. Meitlemeihr. Of course, as a man who was once best buds with a beer-chugging and brown-shirted sodomite like Sturmabteilung commander Ernst Röhm, loved the work of German symbolist painter Franz von Stuck, and bought the rather sexually subversive painting "Leda and the Swan" by Paul Mathias Padua, which was exhibited at the Great German Art Show of 1937 in Munich, Hitler may have been many things, but he was no prude and I am sure he would have gotten a laugh or two out of Mrs. Meitlemeihr, even if he probably would have had director Graham Rose executed were he given the chance.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 27, 2014

7

comments

![]()

Sunday, May 25, 2014

Alucarda

After watching Mexican horror auteur Juan López Moctezuma’s debut feature The Mansion of Madness (1973), I decided it was a better time than ever to watch the stylish blood and boobs celluloid shocker that the director is best known for, Alucarda (1977) aka Alucarda, la hija de las tinieblas aka Sisters of Satan aka Innocents from Hell aka Mark of the Devil Part 3: Innocence from Hell. A lurid and strangely luscious piece of Latina Lolita lesbo artsploitation supernatural horror that takes a more naughty and nubile approach to the nunsploitation subgenre, Alucarda is a great example as to why auteur Moctezuma is not exactly a household name in his homeland as a work that wallows in Catholic sacrilege in a fashion that makes William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) seem as tame as a Cecil B. DeMille biblical epic by comparison. Ostensibly loosely based on Sheridan Le Fanu’s classic 1872 Gothic vampire novella Carmilla, Moctezuma’s third feature is a Sapphic satanic possession piece with vague bloodsucker elements about two 15-year-old Catholic orphan girls who make a pact of lesbo love among themselves, as well as with the devil, after meeting a Svengali-like gypsy hunchback who looks like a large leprechaun. In fact, Moctezuma denied Alucarda was a vampire flick in a 1977 interview and claimed to pay tribute to Bram Stoker and not Le Fanu, stating: “No, even though the title is certainly a homage to Count Dracula. However the film draws on the vampire tradition and in a way the protagonist is a female vampire... but not in the sense of a blood drinker. In fact she has all the powers and attributes of the classic vampire. Except that she doesn't have to drink blood. I've given Alucarda all the vampiric powers Bram Stoker mentions that never get shown in films as well as the ones you'd expect.” Not featuring a single Mestizo actor and starring two Mediterranean nymphets in the lead roles, Alucarda ultimately seems more like a product of Spain or Italy than some sub-schlocky celluloid swill from south of the border. Apparently funded with money the director ‘stole’ from Alejandro Jodorowsky (Moctezuma produced Fando y Lis (1968) and El Topo (1970)), Alucarda is an audacious anti-Catholic diatribe that depicts priests as sexually repressed pervert dictators and nuns as sexless self-flagellating masochists who have a special affinity for pretty preteen girls. Indeed, if anything is demonically possessed and in dire need of an exorcism, it is Alucarda, as a work that mocks and eroticizes Catholic superstition in such a fiercely antagonistic fashion that even a non-Catholic like myself can appreciate its incendiary iconoclasm. Like a hardcore supernatural take on Joël Séria’s Don't Deliver Us from Evil (1971) aka Mais ne nous délivrez pas du mal meets Ken Russell’s The Devils (1971), albeit minus most of the campy elements, Moctezuma's work is one of only a handful of films that I can think of that makes heresy hot yet, unlike most nunsploitation flicks, also manages to be not too hopelessly hokey. For those with a fetish for blood, you also probably cannot do better than Alucarda, as a work featuring rather striking images of seductive young satanically-possessed señoritas soaked in sanguine fluids, which certainly looks more aesthetically pleasing on a woman than ‘spilled seeds.’ De Sade meets Mexican Gothic horror with a tinge of Huysmans and Bava, Alucarda is the film that was practically tailored for true Catholics like my quasi-psychotic Italian-Cuban childhood friend who used to get off to looking at Renaissance paintings of unclad sinners being tortured in hell.

A beautiful young woman (Tina Romero) gives birth to a baby in a cobweb-adorned building covered with gargoyle and demon statues and assumedly dies a couple minutes later after being attacked by some unseen evil entity. Flash forward 15 years later and the baby is now a pretty psychic vampire of sorts named Alucarda (also Tina Romero) who lives in the orphanage section of a Catholic convent that is presided over by a bunch of sexless nuns that look like bull dyke mummies due to their rather strange white cloaks. When a girl named Justine (Susana Kamini) arrives at the convent after her mother dies, Alucarda immediately becomes obsessed with the new young lady and asks her, “Do you want us to be sisters?,” and naturally the shy newcomer agrees. After telling Justine about how one of the sisters has committed suicide, Alucarda goes on a rant about how there can be happiness after death and the two are then approached by a mischievous Gypsy Hunchback (Claudio Brook), who takes them to a small gypsy camp. While Justine is warned by a gypsy woman to not, “believe such a creature. He’ll only tell you lies” in regard the rather grotesque looking Hunchback, Alucarda takes an instantly likely to the deformed degenerate, who gives her a strange dagger, at least until he says, “I see clearly. Your past and future, your dreams. You’ve come from the dew in the forest and there they will be waiting for you. Strange creatures they are, and you must take care. If it obsesses the young lady, here I am and here is my box of charms. If she wishes I will make her free from such a dream…then if the dream comes true, I shall be expecting her,” thus provoking the two girls to runaway in fear. After escaping the Hunchback, the girls end up accidentally discovering a mysterious and seemingly abandoned ancient building with rather sinister architecture which also happens to be the same building where Alucarda was born and her mother died. Upon entering the strange and ominous building, Alucarda becomes extremely excited and tells Justine, “I live in you. Would you die for me? I love you so. I have never been in love with anyone. And never shall. Unless it’s with you.” Alucarda also confesses that she is jealous and how she wants Justine to “love her to death,” so the two youthful lesbian comrades agree to make a blood pact using the knife that was given to them by the Gypsy Hunchback.

Unfortunately, Alucarda and Justine's blood pact is cut short when they open a crypt and become horrified with the decomposed corpse they discover inside. Somehow, the whole experience leaves Justine sick and bedridden, especially after watching a church sermon given by an egomaniacal priest named Father Lázaro (David Silva). While recuperating in bed, Justine is visited by Alucarda, who describes with great excitement how voices talked to her from the woods just like the Gypsy Hunchback said they would and then states in a trance-like state, “Only you and me. Only you and me Justine. We will make them pay. Bit by bit. For all they have taken away from us. Lucifer. Satan! Lucifer!” After ripping a cross necklace from Justine’s neck, Alucarda declares, “we shall make them pay” (in regard to the nuns and priest, who she believes has caused Justine’s sickness) and then the Gypsy Hunchback somehow magically appears out of nowhere, strips the girls of their clothing, and makes them more or less make a pact with the almighty Great Satan. While making the pact, the two girls lick blood from one another’s lips and tits and Baphomet even makes an appearance, thus somehow transporting the two proto-Goth gals to a lesbian witch orgy. Meanwhile, a loving nun named Sister Angélica (Tina French) pleads to god to save Justine from the devil, which causes the nun to levitate and her face to severely hemorrhage. Now possessed by the devil, Justine later declares in her bible class, “God with his lack of knowledge does not understand the truth, and opposes it with false thoughts and prayers” and the two friends proceeds to chant: “Satan, Satan, Satan, Our lord and master. I acknowledge thee as my God and Prince. I promise to serve and obey thee as long as I shall live. I renounce the other God and all the saints.”

Needless to say, Justine does not live long as Father Lázaro forces her to an endure a brutal S&M-like exorcism that involves cutting her up naked body (they strip her to prove that she has the ‘mark of the beast’) after the padre comes to the conclusion that the girls are victims of the devil’s evil messenger, a heliophobic demon—a sixth category devil who hates light. Indeed, after Alucarda scares the Priest by telling him that she worships life and he worships death, Father Lázaro forces all the nuns to get half-naked and engage in sadomasochistic flagellation and decide an exorcism is the only way to rid their church of the satanic conspiracy. When a doctor named Dr. Oszek (Claudio Brook) walks in on the exorcism and sees Justine’s naked corpse, he becomes enraged and declares, “the most shameful thing I have ever been a witness to. This isn’t the 15th century, I thought that reason replaced superstition. This is not an act of faith…this is the most primitive expression of ignorance I have ever seen. You… You…have just killed Justine.” After damning the priest and nuns, Dr. Oszek takes Alucarda with him and introduces her to his blind teenage daughter Daniela (Lili Gazara), not realizing that the girl he has exposed to his progeny is demonically possessed. Naturally, being a little lesbo Lolita, Alucarda takes an instant liking to Daniela and makes her promise to stay with her, which she does. Meanwhile, back at the convent, Justine’s corpse somehow disappears and a nun is burnt alive, with her corpse later rising from the dead and spitting out blood in a rather rude fashion. Naturally, a priest decides to decapitate the demonic zombie nun. Eventually, Sister Angélica discovers Justine’s naked undead body inside of a coffin full of blood. While Sister Angélica manages to stop zombie-vampire Justine from killing her at first, Dr. Oszek throws holy water on the undead she-bitch, thus provoking her to bite the sister’s throat, which naturally kills the holy woman of god. In the end, demonically possessed Alucarda becomes hysterically homicidal and begins killing countless priests, nuns, and monks with flames summoned from hell, though she eventually drops permanently dead after staring at a giant burning crucifix. Naturally, Dr. Oszek and his daughter Daniela escape relatively unscathed.

In terms of films about the demonic possession of Latina Lolitas, you will certainly be hard-pressed to find one better than Alucarda. In fact, the film is certainly cream of the celluloid crop when it comes to nunsploitation, exorcism films, and Mexican horror cinema as well, though not that I am any sort of connoisseur when it comes to these typically sleazy and sickeningly superficial types of films. I can say, however, that as a hopeless cynical who lacks a superstitious mind, I found Alucarda to be exceedingly effective, as the sort of film that I expected The Exorcist to be but was not. Indeed, featuring nuns that dress like mummies and bleed profusely out of their naughty bits, a melancholy sister who keeps her face about a foot or two away from a dead teenage girl’s bare postmortem bush, and a towering Baphomet randomly appearing during a satanic Sapphic blood pact between two titillating 15-year-old girls, Alucarda is a hard film to top in terms of salacious supernatural horror, especially considering the film manages to depict all these typically distasteful things in a shockingly cultivated way. Apparently, a sequel entitled Alucarda Rises From The Tomb was in the works, but director Juan López Moctezuma unfortunately died before he could ever realize it. Personally, I am one of those rare people that actually prefers the director’s first feature The Mansion of Madness to Alucarda, but that probably largely has to do with the fact that I was not brought up Catholic and I prefer psychedelic arthouse aesthetics and wayward dark humor to most supernatural horror films. Indeed, Alucarda features none of the Jodorowsky-esque surrealism and Theatre of Cruelty-like spastic acting that made The Mansion of Madness so memorable. Indeed, I cannot say that the idea of demonic possession is something that scares me, but then again maybe it is because I have met far too many moronic, ugly, and morally repugnant people to be able to be horrified at the sight of a nubile naked girl covered in vital fluids declaring her love for the fallen angel Lucifer. For those that cannot stand hysterical young women incessantly screaming as if suffering from a deadly orgasm, as well has hyper histrionic acting, Alucarda may seem like a grating slice of celluloid hell. A hostilely heretical work where madness, eroticism, violence, and spirituality become indistinguishable, Alucarda is ultimately an innately iconoclastic work that relentlessly mocks the irrationality of the Catholic Chuch yet at the same time criticizes the hyper rational man of science, thus making for a film that is eclectically misanthropic, albeit in a fairly cryptic fashion that is actually quite admirable. Indeed, as someone who typically loathes big fat whiny atheist humanists more than priests and nuns, I appreciated the fact that the doctor character featured in the film was also portrayed as a self-righteous fool of sorts, but I digress and will close by saying that Alucarda is easily the most elegantly visceral and hatefully violent yet erotically-charged lesbian quasi-vampire flick I have ever seen and that Jess Franco and Jean Rollin probably could have learned a lot had they taken the opportunity to watch it.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

May 25, 2014

10

comments

![]()

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.