Tuesday, December 31, 2013

Manson Family Movies

Undoubtedly, if Jim Van Bebber’s The Manson Family (2003) is the greatest, most aesthetically ambitious, and psychedelic-driven Manson-themed movie ever made, Manson Family Movies (1984) directed by self-proclaimed ‘aesthetic nihilist’ John Aes-Nihil (The Goddess Bunny Channels Shakespeare, The Drift) is the most obsessive, gritty, pathologically tasteless, and historically accurate (anti)tribute to the dirty derelict deeds of the hillbilly hobo antichrist and his fucked family of fallen bourgeois degenerates. Indeed, while occult guru Nikolas Schreck’s documentary Charles Manson Superstar (1989) probably provides the best and most objective look at Manson Christ and his crazy gals, Manson Family Movies is the most aggressively visceral and vicious look at the sordid story and thus makes for singular viewing (dis)pleasure that simultaneously manages to both trivialize the bloody beatnik events and aesthetically terrorize the viewer in an uncompromising fashion that one would expect from a mad man. Inspired by the supposed urban legend that Manson and his acidfreak pseudo-family had actually filmed their aberrant activities and even went so far as creating the murders for posterity, Manson Family Movies is an innately morally retarded no-budget piece of pathetically provocative celluloid shit that was shot on consumer grade 8mm film stock so as to give it an audaciously authentic essence as if one of the family members was sober enough to keep a camera rolling as the rest of the gang partied homicidally hard. Indeed, shot silently and featuring not a single line of audible dialogue, Manson Family Movies certainly feels like a home movie from hyper-hedonistic hippie hell and a work that seems like it was filmed by a spastic speed addict for his own aimless brain dead amusement. Described by cine-magician Kenneth Anger, who was once a mentor of sorts to Manson associate/killer Bobby Beausoleil (who starred in Anger’s Invocation of My Demon Brother (1969) and scored Lucifer Rising (1972) while in prison), with the highly flattering compliment that it, “Looks like the real thing,” Manson Family Movies is undoubtedly the delightfully dubious expression of a fellow with a rather foul Manson obsession. Probably the most ambitious and oddly obsessive cinematic attempt to recreate an infamous true crime case, Manson Family Movies was shot at the actual locations of the events leading up to, and including, the flower-power-exterminating Tate-LaBianca murders (including the very spot where the hippie killer dropped the bloody clothing of Sharon Tate and her fellow victims). A mischievously merry and wantonly witchy Mansonite jamboree movie, Manson Family Movies features gay negro drag queen maids reading Nietzsche, three different (non)actresses playing Susan Atkins aka Sadie Mae Glutz, degenerate hippie bastards in Nazi helmets sieg heiling the police, and a hip and happening neo-völkisch hillbilly folk soundtrack by Mr. Alpha-Anti-Hippie himself; Charles Manson.

As anti-aesthetic auteur John Aes-Nihil revealed in the audio commentary for the Cult Epics dvd release of Manson Family Movies, Charles Manson was played by a strange fellow (‘Rick the Precious Dove’) who had the dignified distinction of being an ex-Green Beret, five foot two, half Mexican/half German by ancestry, and apparently being “rather psychotic.” Interestingly, it is rumored that the real Charles Manson was the bastard son of a mulatto, but I digress because whatever the real racial stock of Mr. Manson, micro Mestizo-Kraut ‘Rick the Precious Dove’ certainly can pass for the crazed cult leader, even if he is a slight bit more swarthy than the real man. Opening with Manson strumming his guitar and subsequently carnally manhandling Sadie Mae Glutz, Manson Family Movies ultimately takes an abridged fragmented approach to cinematically telling the torrid tale of the life and times of the Manson Family. Hanging out at Spahn ranch, one of the mad Manson girls receives cunnlingus (Aes-Nihil claims this scene was totally unsimulated) from the rather voracious ranch owner George Spahn (played by ‘Palmo’) in a less than pretty quasi-pornographic scene. Of course, Lucifer-like Manson associate Bobby Beausoleil (‘Porn Michael’) and a couple of the gals pay a visit to hippie teacher/dope Gary Hinman and torture him for a couple days because he purportedly sold them bad acid. Being a deluded Zen Buddhist, homo hippie Hinman does not even put up a fight and even goes so far as peacefully handing a weapon to one of his deranged torturers. Manson also pays a visit to the Hinman home and cuts the drug dealer’s ear with a sword. After Beausoleil wastes Hinman, the Manson girls write “Political piggy” on the wall to make it seem like the Black Panthers committed the murder. Meanwhile, a black tranny maid (The Cosmic Ray) religiously reads from Friedrich Nietzsche’s posthumously released tome The Will to Power and carefully dusts a LP soundtrack for Valley of the Dolls (1967) starring Sharon Tate. Indeed, the black tranny is Tate’s maid and the shemale spade also force-reads excerpts of The Will to Power to the bimbo-like babe as if her life depends on it. Of course, the Manson family eventually pays an unexpected visit to the Tate-Polanski home and they slaughter all the inhabitants of the house, but not before making macabre jokes about the fact the actress is pregnant and her baby will die a violent death as well. In what is easily the most artful and transcendental scene of Manson Family Movies, Charlie is lovingly crucified by his family in a scene rivaling the campy crucifixion from The Devils (1971) directed by Ken Russell. In the final scene of Manson Family Movies in a sardonic scenario auteur Aes-Nihil proudly described as “a moment of devout cynicism,” three members of the family throw away the gigantic crucifix that Charlie was previously hanging from into a park trashcan. Quite fittingly, Manson Family Movies concludes with the 1970 Charlie quote, “It wasn’t my children who came at you with guns and knives, it was your children,” thus demonstrating Aes-Nihil's sheer and utter contempt for the American mainstream.

Featuring nil dialogue, upwards of three amateur actors playing a single character (thus making it nearly impossible to discern who is who during various scenes), a horribly homely and overweight Sharon Tate smiling as she is violently stabbed in her fetus-filled stomach, unsexy unsimulated sex featuring elderly men on LSD, a sassy negro tranny with a nasty Nietzsche obsession, bargain bin blasphemy of the culture-less American sort, and happy-go-lucky ultra-violence of the totally unbelievable variety, Manson Family Movies is certainly a film that epitomizes the phrase “trash cinema,” so it should be so no surprise that the ‘Pope of Trash’ himself, John Waters, stated of the film: “Manson Family Movies is a primitive, obsessional, fetishistic tribute to mayhem, murder and madness. Enough to appall even the most jaded VCR junkie... The home movie effect really added to it. Attention to fetishy detail was really astounding—Abigail’s scarf, Tex's gun, plus Sadie, Tex and G. Spahn looked more like the originals than Helter Skelter. Very rude—all the rumors, MDA deal, Leno the bookie, Tate S&M... I liked the Valley of the Dolls and Nico touch. The most obscure was Leno's vacation—I had never even imagined those sights.” Indeed, for those with little knowledge and/or interest in the Manson Family and their macabre misadventures, Manson Family Movies will probably prove to be the most brazenly banal, badly directed, and patently pointless film ever made, but for the already initiated, Aes-Nihil’s Mansonite fetish flick is a tastelessly tasty treasure trove of serial killer-like pathological obsession and homicidal hillbilly aesthetic majesty.

For those familiar with Manson’s oftentimes dark and intensely idiosyncratic folk music, Manson Family Movies plays like a genuine Mansonite musical. Also featuring music by director Aes-Nihil’s band Beyond Joy and Evil, The Beatles (namely “Helter Skelter”), Patty Duke’s theme from Valley of the Dolls, Richard Wagner’s “Liebestod,” and a couple random punk tracks, Manson Family Movies—a whimsical work erratically synthesizing cultural ingredients from both high and low culture—is certainly a putrid piece of celluloid ‘aesthetic nihilism’ directed by an auteur who personifies being a ‘degenerate’ in the truest Nordau-esque meaning of the word. In addition to receiving critical acclaim from such great queer auteur filmmakers as Kenneth Anger and John Waters, Manson Family Movies also received perverse praise from unhinged underground filmmaker George Kuchar, who stated personally to director Aes-Nihil, “I remember your film very well and it looked SCARY! It had an authentic feel to it that made us squirm. Well, it looked gritty and homespun and made me NERVOUS. Keep up the original and disturbing atmosphere.” A sort of misbegotten movie marriage between Roger Watkin’s Manson-inspired flick The Last House on Dead End Street (1977) meets the audaciously amateurish art-trash of Harmony Korine’s Trash Humpers (2009), Manson Family Movies certainly makes for a great, if not one-sided, date with the celluloid gutter. For those that enjoyed Manson Family Movies, contemporary punk artist Raymond Pettibon’s somewhat inferior shot-on-VHS epic of lo-fi video-art-filth The Book of Manson (1989) also makes for mandatory viewing. A sub-cult classic of the crazed campy sort, Manson Family Movies—in its outstanding aesthetic ineptitude, innate immorality, and general narrative incoherence—is ultimately a reminder why there will probably never be a definitive Manson family movie as Hollywood will never touch the subject in a serious and sincere manner and those genuine underground auteur filmmakers that are willing to dive deep in the world of Helter Skelter lack the sanity, budget, and production values to execute it properly.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

December 31, 2013

13

comments

![]()

The Last Horror Film

Personally, I have always felt that the iconic slasher flick Maniac (1980) directed by William Lustig and starring Guido cinematic hero Joe Spinell was more darkly humorous than anything. After all, what is more funny than a wayward wop with malignant mommy issues talking to drag queen-like mannequins?! Naturally, when I discovered horror comedy The Last Horror Film (1982) aka Fanatic—a sort of pseudo-satire of Lustig’s slasher flick (the film was purportedly released under the title Maniac 2: Love to Kill on VHS in West Germany) starring Maniac leads Joe Spinell and Caroline Munro—I knew it was a film I had to see and would probably rather enjoy, if only in a novelty ‘junk cinema’ sort of way. A pseudo-horror-film-within-a-horror-film in the spirit of Michael Powell’s Peeping Tom (1960) and Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver (1976) meets John Waters’ Serial Mom (1994) and Lucio Fulci’s Nightmare Concert (A Cat in the Brain) (1990), The Last Horror Film is a campy quasi-horror-of-personality work about a maniac Guido taxi-driver from NYC who absurdly believes he has what it takes to be the next great auteur of horror cinema and travels all the way to the Cannes Film Festival in France to proposition a popular Screen Queen to star in his would-be-movie, but instead ends up killing a bunch of film producers and other degenerate Hollywood types and makes a cinéma vérité-like snuff flick instead (or so the viewer thinks). Rather bizarrely directed by Anglo-Jew David Winters—a dancer/dance choreographer turned film director/producer who is probably best known for directing the Alice Cooper music concert documentary Welcome to My Nightmare (1975) and the Romeo and Juliet-themed skateboard flick Thrashin' (1986) starring Josh Brolin—The Last Horror Film is certainly a charmingly trashy 1980s celluloid cheese that seems to mock the horror genre and the media hysteria surrounding it rather than paying actual tribute to the much maligned genre. Actually shot guerrilla style without permits at the 1981 Cannes Film Festival where Joe Spinell apparently blew a good portion of the film's budget on booze and other hedonistic pursuits, The Last Horror Film is essentially a cinephile’s sloppy wet dream as a work that features shots of billboards from such great films as Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession (1981), Ruggero Deodato’s Cannibal Holocaust (1980), István Szabó’s Mephisto (1981), and John Waters’ Polyester (1981), among various others. Featuring star Joe Spinell bickering with his real-life mother Filomena Spagnuolo in his real-life apartment, The Last Horror Film is not only a lovingly loony tribute to the underappreciated Italian-American actor, but the closest thing to a real sequel to Maniac.

As depicted in the opening scene of The Last Horror Film, Vinny Durand (Joe Spinell) is a perversely pathetic loser who masturbates in public movie theaters to tasteless slasher flicks featuring fake blonds with fake tits being butchered by maniacs. While his friends berate him for drooling over horror movie magazines as if they are porno mags and his overbearing mother (Filomena Spagnuolo aka Mary Spinell) believes he should be happy with his undignified job as a taxi driver, Vinny is a proletarian megalomaniac with deranged dreams who rather absurdly believes he will be the next Alfred Hitchcock and he even seems willing to kidnap and kill to achieve his grandiose goals. Having gone so far as writing a screenplay, dumbass Durand firmly believes that international cult film superstar and so-called “Queen of Horror Films” Jana Bates (Caroline Munro) will be the star of his upcoming movie. Unfortunately, being a sub-literate buffoon with no real world experience (let alone experience working in Hollywood), Vinny decides simply flying to the Cannes Film Festival and stalking Ms. Bates will be his best bet. Certainly crazy but not lazy, Vinny takes his tip money from taxi driving, buys a plane ticket, and heads to the Cannes Film Festival where he discovers a virtual heaven on earth of both carnal and cinematic treasures, though the hapless would-be-filmmaker seems incapable of obtaining both. Naturally, Vinny attempts to hookup with Jana Bates, who is at the festival to promote her latest horror excursion Scream, but he is denied access to her every single time. When Vinny attempts to call Bates’ manager/ex-husband Bret Bates (Glenn Jacobson) about his script, he is rudely hung up on. When Jana Bates heads to a press conference with her producer Alan Cunningham (Judd Hamilton), she receives anonymous flowers with a strange note reading, “You've made your last horror film.” Not long after, Bates goes to see her manager/ex-husband Bret in his hotel room, but instead she is greeted by his bloody corpse, which later vanishes into thin air when the police arrive to investigate.

A stereotypical Hollywood Hebrew named Marty Bernstein (Devon Goldenberg) bumps into Vinny, who begs him to promote his movie, and becomes rather suspicious of the strange fellow after finding out that film director Stanley Kline (director David Winters) and his personal assistant Susan Archer (Susanne Benson) have also received strange threatening notes similar to the one Jana Bates received. Marty goes to the police about Bret Bates’ dubious death, but the cops think it is merely a publicity stunt. After receiving a note purportedly from Bret Bates, Marty finds himself axed to death by an ominous figure wearing a black cloak. Of course, Stanley Kline and Susan Archer are subsequently brutally murdered as well and the mysterious killer has filmed all these deaths in a somewhat voyeuristic Peeping Tom-esque fashion. Meanwhile, Vinny begins filming his own horror movie when not acting like a maniac while dressed in drag and schizophrenically talking to his suave imaginary doppelganger. Eventually, Vinny gets the gall to sneak in Jana’s hotel room with a bottle of champagne in hand, but startles the little lady while she’s in the shower. Vinny asks her to play the lead role in his movie, but Jana belittles him, so the would-be-auteur smashes the champagne bottle and menacingly threatens the Scream Queen. Jana ultimately manages to escape from Vinny’s wrath and seeks sanctuary in her producer Alan. Later, Vinny disguises himself as a police officer, heads to the Cannes award ceremony and manages to kidnap Jana by knocking her out with chloroform. With Jana is unconscious in the passenger seat of a rental car, Vinny heads to a castle in the French countryside to film a scene for his horror movie where he plays Dracula and the Scream Queen plays his involuntary victim. In an absurd twist, Bret Bates shows up to the castle with a gun and movie camera and reveals that he is the real killer and has merely used Vinny as the perfect dimwitted fall guy. Jealous over his ex-wife's new life as a very desirable free woman and international super star, Bret had decided to seek revenge. Luckily, Vinny manages to kill Bret in a leatherface-style fashion by beheading him with a chainsaw. In another climatic twist, it is revealed at the conclusion of The Last Horror Film that everything that happened at the Cannes Film Festival was not as it seemed and things conclude on a rather happy note with Vinny having completed and released the trashy horror film he always dreamed of. In the end, Vinny screens his directorial debut for his mother and she asks him afterward if he has, “Got a joint?,” and the mother and son proceed to share a nice sized blunt.

As Maniac director William Lustig revealed in the Troma dvd release of The Last Horror Film regarding the production of the film: “He (Luke Walter) and Joe would go shoot scenes for the movie by themselves…It was not a conventionally made horror film… It was a film that was kind of an improv.” Indeed, apparently The Last Horror Film was a real-life fantasy flick of sorts for Joe Spinell where he could vacation in Cannes, party with his friends, and make a movie and one certainly gets that feeling while watching the film. The Last Horror Film is by no means a great movie, let alone a masterpiece or ‘thee last horror film,’ but it is a fun little flick starring an actor who deserved more lead roles in films. Undoubtedly, with its murder scenes shot from the perspective of the viewer, The Last Horror Film clearly influenced the 2012 remake of Maniac directed by Franck Khalfoun and produced by Alexandre Aja. Superlatively stupid satirical schlock featuring Sicilian savage Spinell dressing in drag, talking to his more dapper doppelganger, and acting like a general boorish jackass, The Last Horror Film is certainly a work made for the fans and the fans only. Of course, in its depiction of a time when the Cannes Film Festival actually played masterpieces like Żuławski’s Possession, The Last Horror Film unwittingly depicts the end of a zeitgeist when European arthouse cinema began to die and banal Hollywood blockbusters began to rape the minds of the entire world. At least with a film like The Last Horror Film, one knows the film is honest in its innate tastelessness and artlessness.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

December 31, 2013

8

comments

![]()

Monday, December 30, 2013

Innocence (2004)

Female coming-of-age flicks, especially of the actually female-directed sort, are not exactly common, but it seems the emasculated French pump out the best and most patently perverse films from this niche subgenre, with Catherine Breillat’s Fat Girl (2001) aka À ma soeur! certainly being a notable and rather nasty example. Undoubtedly, the most innately idiosyncratic and downright bizarre girly coming-of-age flick I have ever seen is Innocence (2004) directed by Argentinean-born auteur Gaspar Noé’s Bosnian-French wife Lucile Hadžihalilović (La bouche de Jean-Pierre, Good Boys Use Condoms). Rather loosely based on a novella by degenerate Teutonic playwright Frank Wedekind entitled Mine-Haha, or On the Bodily Education of Young Girls (1903) aka Mine-Haha oder Über die körperliche Erziehung der jungen Mädchen—a work that was rather unfortunately lauded by Judeo-Marxists Leon Trotsky and Theodor W. Adorno, as well as mischling diva Marianne Faithfull—Innocence is certainly no less controversial than the sordid and gritty cinematic works of Hadžihalilović’s hubby Noé (to whom she dedicated the film), though for entirely different reasons. Indeed, with its various scenes of fully naked preteen girls frolicking around lakes and whatnot, Innocence is certainly the sort of work that would attract the larger male pedophile population were the film not so pathologically plodding and steeped in atmosphere-driven ambiguity. Like her blatant filmic influence David Lynch, Hadžihalilović has stated in various interviews that it is up to the viewer to find their own meaning while watching Innocence, for which I certainly respect the filmmaker as the film features nil of the far-left novelty intellectualism that oftentimes plagues frog cinema. Like Picnic at Hanging Rock (1975) directed by Peter Weir meets A Day with the Boys (1969) directed by Clu Gulager meets The Spirit of the Beehive (1973) directed by Víctor Erice meets Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) in keen color and written from the perspective of a little girl, Innocence is a visceral yet esoteric work where ritual and routine drive the film’s seemingly nonsensical storyline. A somewhat ironically titled work, Innocence is a film about the loss of innocence every member of the fairer sex must face when evolving from a prepubescent girl into a physical and mental woman who longs for a man. Set in a bizarre French boarding school for girls where new students arrive naked in tiny coffins and are inevitably molded quasi-militaristically into women if they are successful with their secret studies, Innocence is an ominous, oneiric, and foreboding flick that even manages to transcend Terry Gilliam’s Tideland (2005) in terms of its bewildering portrayal of the complete and utter confusion that is female childhood. Undoubtedly an innately flawed film that I found to have various glaring annoyances that were clearly executed by someone with a soft, if not artistically strong, female touch, Innocence is certainly a work that will more appeal to women and probably also effeminate gay men, but will certainly provoke a response in all viewers, namely due to its various scenes of nude little girls, obsessive hermetic symbolism, and nonlinear storyline.

One thing that my girlfriend, who ultimately hated the film, and I found particularly annoying about Innocence is that the prepubescent protagonist, Iris (Zoé Auclair), is an Asian of unmentioned origin who sticks out like a sore yellow thumb in an exclusively white and seemingly ‘classical’ French boarding school, as if auteur Hadžihalilović wanted to make sure her film was ‘multicultural’ enough for the average French cultural Marxist cinephile. Like all the new students at the institution, Iris inexplicably arrives naked in a coffin, as if she has been reborn a baby vampire. Instead of being greeted by the school’s teachers/adults, Iris is welcomed and shown the ropes of the all girls school by the little girls that attend it. The pupils at the school are differentiated by age with colored ribbons that they wear in their hair, with the youngest student wearing red (Iris’ color) and the oldest wearing violet. Almost immediately upon arriving at the school, Iris becomes infatuated with an older girl named Bianca (Bérangère Haubruge), who the newcomer looks up to as a mentor and seems to have almost lesbian feelings for. Iris has no clue how she arrived at the school and complains about missing her brother, but her pleas are only met with the reassurance that she is now at ‘home.’ Despite lacking control of the students in many regards, the teachers are rather authoritarian and seem like frigid dykes who want to break little girls just as they were once broken long ago. When one of the little girls, Laura (Olga Peytavi-Müller), attempts to escape from the school on a leaking rowboat, she ultimately drowns and her corpse is burned up in the coffin she arrived in a ritualistic manner in front of the entire population of the institution as if a warning to all other girls at the school to not attempt to escape. Indeed, fear is the foremost tool used to keep the girls in check. When a rather homely girl that looks like Anne Frank, Alice (Lea Bridarolli), lashes out due to the fact she was not picked to ‘graduate’ from the school, she later runs away and disappears and the teachers tell the rest of the girls to forget she ever existed. A lady named Mademoiselle Eva (Marion Cotillard), who teachers the girls ballet and the finer points of being a fair lady, does the honor of setting the coffins of dead girls on fire, while a cunty cripple with a cane named Mademoiselle Edith (Hélène de Fougerolles) acts as a sort of adversarial character. Notably, Iris is told that if she breaks the rules at the school (i.e. attempts to escape), she will be punished with being forced to stay there forever like the female teachers, who never developed into real woman as sexless spinsters who have dedicated their lives to teaching little girls (after all, those that cannot do teach!) In the end, Iris’ best bud Bianca graduates from the school and almost immediately finds a ‘man’ upon entering the real world in a symbolic scene clearly indicating she has finally reached womanhood.

In an interview, auteur Lucile Hadžihalilović stated regarding Innocence and her expectations regarding how certain audiences will respond to the film: “I think the audience’s reaction will vary between men and women. Naturally, I think it’s easier for women to identify with the young girls. They’ll understand it more quickly and directly. Their own lives will be evoked. It’s a bit more complicated for men since there are no male characters in the film. So I think their own view of the young girls will be evoked.” Indeed, I would be lying if I did not admit that I could not completely lose myself in the film as Innocence was clearly made by a woman with a ‘nostalgic’ sense of childhood, which Hadžihalilović confirmed in an interview when she confessed: “Someone told me that they think my film portrays what it is to be a normal girl, in a normal school who conjures up that world in their imagination to recount their experience. In that sense, yes, my film is completely autobiographical.” Somewhat peculiarly, Innocence is also rather heavy on “nature-worship” and reminded me of a Lynchian take on völkisch National Socialist propaganda flicks like Enchanted Forest (1936) aka Ewiger Wald. In fact, auteur Hadžihalilović confessed regarding her interest in adapting Mine-Haha, or On the Bodily Education of Young Girls, “One of the elements that I really liked in Wedekind’s story was its pantheism. Maybe it’s personal and related to my childhood, but I have the impression that children live in nature.” Undoubtedly, if one learns anything while watching Innocence, it is one cannot stop the power of nature and that nature knows no morals.

Indeed, if there was anything I could relate to in Innocence, it is the film’s mystical depiction of nature and its organic majesty because as a child I loved nothing more than getting lost in the woods and feeling like I was one with the animals, trees, and water. Of course, as symbolically depicted at the conclusion of Innocence when Bianca graduates and heads to the city, most people seem to lose their affinity and respect for nature when they become adults. Notably, Innocence is not the only film based on Wedekind’s Mine-Haha, or On the Bodily Education of Young Girls, as director John Irvin made an inferior yet much darker lesbo-themed adaptation of the novella entitled The Fine Art of Love: Mine Ha-Ha (2005) starring Jacqueline Bisset. A film that will probably only ironically appeal to dubious individuals into arthouse child porn like Maladolescenza (1977) as well as female cinephiles looking to get in touch with their inner child, Innocence ultimately proves Lucile Hadžihalilović is a true female talent who has yet to make her masterpiece and who does not need to rely on cliché feminist/left-wing politics to attract praise from critics like most female filmmakers do. Make no mistake about it, Innocence is a slow and oftentimes plodding arthouse work, but Hadžihalilović is clearly an uncompromising and intuitive artist in the Herzogian sense who takes cinema very seriously as an artistic medium and who is not afraid to alienate the majority of filmgoers, which is certainly something I can respect. Indeed, while I know next to nothing about Hadžihalilović, it is quite clear to me that Gaspar Noé has found his soul mate and she clearly lost her innocence long ago, but like her film demonstrates, innocence is something one does not truly understand until it is lost forever.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

December 30, 2013

10

comments

![]()

Saturday, December 28, 2013

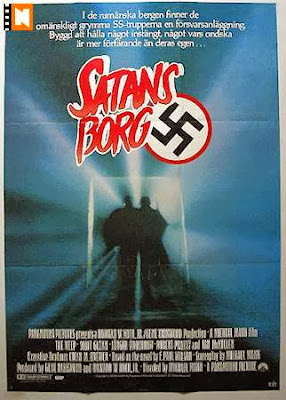

The Keep (1983)

Undoubtedly, a Gothic horror World War II flick set in war torn Romania featuring a soundtrack by electronic krautrockers Tangerine Dream sounds like a rather delectable prospect, but somebody made a major mistake when they granted Hollywood Hebraic hack Michael Mann (Thief, The Last of the Mohicans) the once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to direct such an innately ambitious and easy-to-botch cinematic work. Indeed, The Keep (1983)—a film based on the 1981 novel of the same name, which was the first volume in a series of six novels known as The Adversary Cycle written by American sci-fi novelist F. Paul Wilson—is a work that had all the potential of a ‘blockbuster masterpiece’ (an oxymoron if there ever was one!) and would eventually earn cult status among loyal fans, but director Michael Mann ultimately disowned the film and even prevented its release on dvd, which is certainly no surprise as it is an aesthetically pleasing mess of the innately incoherent and horribly uneven sort, not to mention a perfect example of how Hollywood butchers films. Although a little over 90 minutes in its present form, Michael Mann’s original cut of The Keep was a whopping 3 ½ hours in length, which is certainly why the film is an epic abortion with a jumbled and disjointed storyline. A sort of extremely loose reworking of the Golem story from Jewish folklore meets Castle Keep (1969) directed by Sydney Pollack minus the humor, The Keep childishly wallows in Spielberg-esque anti-Nazi clichés and emphasizes heavily stylized action sequences and then-state-of-the-art special effects over character development and sensible linear storytelling. In fact, director Mann once described the film as, “A fairy story for grownups. Fairy tales have the power of dreams - from the outside. I decided to stylize the art direction and photography extensively but use realistic characterization and dialogue,” yet The Keep has a moronic moral compass that seems like it was created by the bastard Judaic half-brother of the Brothers Grimm and certainly does not seem like it was created with grown adults in mind. Indeed, a supernatural and pseudo-spiritual ‘scary’ Shoah flick for a degenerate generation of effeminate braindead fanboys who see Luke Skywalker as their Christ and see any cinematic depiction of Hitler as Satan and German soldiers as demons, The Keep is certainly the most philistine extreme of hapless holocaust propaganda and the soundtrack by Teutonic musical geniuses Tangerine Dream makes it seem all the more bizarre. Indeed, I would be lying if I did not admit The Keep is my favorite Israelite-directed anti-Nazi propaganda flick as it may be an absurdly muddled movie with Streicher-esque caricatures of German soldiers, but it is also an endlessly entertaining ‘popcorn flick’ that acts as a sort of cinematic equivalent to a hokey haunted holocaust museum.

Set in 1941 following the commencement of Operation Barbarossa at the Dinu Mountain Pass of the Carpathian Alps in rural Romania, The Keep begins with the arrival of a German Wehrmacht unit led by ‘nice Nazi’ Captain Klaus Woermann (Jürgen Prochnow). After two of Woermann’s more criminally-inclined kraut soldiers attempt to steal a glowing cross icon they mistake for silver in an uninhabited citadel (aka “The Keep”), they unwittingly unleash an evil Golem-like entity named Radu Molasar that had been imprisoned in the ancient keep. Naturally, metaphysical monster Molasar begins killing off kraut soldiers faster than the snow in Stalingrad, which raises the suspicion of the German army. Eventually, a genocidal SS Einsatzkommando unit led by a nefarious Nazi named SD Sturmbannführer Eric Kaempffer (Gabriel Byrne) is called in to investigate the mysterious murders and restore order in the medieval-like Romanian village. Of course, the first thing Kaempffer has his killer kraut commandos do upon arriving in the town is have a group of wholesome Romanian men executed in retaliation for the deaths of murdered Wehrmacht soldiers, but also to prevent any other murders. A callous National Socialist ‘true believer,’ Kaempffer firmly believes the deaths are the result of communist partisans. At the recommendation of a lying Romanian priest named Father Mihail Fonescu (Robert Prosky), the Germans have a Romanian Jewish historian named Professor Theodore Cuza (Ian McKellen) and his daughter Eva (Alberta Watson) fetched from a concentration camp to help solve the mystery murders as both of them somehow have special esoteric knowledge regarding the Keep. Professor Cuza manages to translate a dead language similar to Romanian written on the wall of the citadel and not long after two SS men attempt to rape his daughter, but she is ultimately saved by Jewish monster Molasar. Gracious for Molasar’s seemingly selfess heroism, Cuza ultimately befriends and makes a Faustian pact with the monster, who also cures the Professor of his debilitating case of scleroderma and gives him eternal youth. Meanwhile, a man with supernatural powers named Glaeken Trismegestus (Scott Glenn) senses something evil is stirring in the Keep and begins to travel all the way from his hometown in Greece to the Romanian village. Of course, Kaempffer continues to kill Romanian peasants and eventually kills Klaus Woermann for his anti-Nazi rhetoric and insubordinate behavior, but anti-anti-Semite Molasar eventually kills the sadistic SS man. Additionally, not unlike Frank Cotton from Clive Barker’s Hellraiser (1987), Molasar begins to take a more human form the more powerful he becomes. When gallant hero Glaeken eventually arrives in the Romanian village to stop Molasar, Professor Cuza attempts to have him killed. In the end, Professor Cuza finally comes to the realization that Molasar is not a saint and Glaeken battles the Golem-like creature, ultimately using his body to once again imprison the all-evil creature in the citadel.

Director Michael Mann essentially summed up the ‘message’ of The Keep when he stated regarding the Second World War, “There is a moment in time when the unconscious is externalized. In the case of the 20th Century, this time was the fall of 1941. What Hitler promised in the beer gardens had actually come true. The greater German Reich was at its apogee: it controlled all Europe. And the dark psychotic appeal underlying the slogans and rationalizations was making itself manifest.” With its unintentionally strange and rather superficial scenes of old Jewish intellectuals lounging in death camps in style, suavely dressed SS of the sadistic megalomaniac sort going on deranged anti-communist diatribes, absurdly childish and cheesy caricature-driven portrayal of good and evil, unflatteringly romanticized depiction of Romanian peasants, and innate irrationalism, The Keep ultimately seems like a warped post-Auschwitz religious parable directed by an atheistic Jew for consumption by feeble minded goy Christians of the pathetically superstitious sort. That being said, The Keep still manages to be a captivating work, as if it was directed by the ½ Hebraic son that H.P. Lovecraft never had with his short-lived Jewess wife Sonia Greene. In a sense, The Keep is a cinematic tragedy of sorts as it has so many strong and strikingly aesthetic and even thematic elements, but is ultimately plagued by its own equally glaring aesthetic and thematic weaknesses. Indeed, with conspicuously contrived and ludicrous quotes from evil antagonist Sturmbannführer Kaempffer like, “The people that go to these resettlement camps… There are only two doors… One in and one out… The one out is a chimney,” The Keep is undoubtedly a work that is also tastelessly cheapened by the director’s personal political/religious bias. Indeed, you know there is a problem with a World War II film when the evil Nazi antagonist is so artificial and anti-human in persuasion that he makes Ralph Fiennes' portrayal of Amon Goeth in Steven Spielberg’s Schindler's List (1993) seem to possess as much depth as a character from an Ingmar Bergman film. Rather repellently, The Keep also makes absurd Marxist revisionist references to the Spanish Civil War by making it seem as if the ‘good guys’ (aka communists) tragically lost against Satan’s fascist army. Indeed, featuring a hopelessly redundant hodgepodge of softcore Marxist clichés and ludicrous leftist mysticism, decidedly dumbed down dichotomies between good and evil, demonization of German soldiers as killer kraut Ken dolls, and tasteless glorification of communist/Jewish partisans and Jewish intellectuals, The Keep is ultimately an awe-inspiring film as cinema history’s most ambitious agitprop neo-fairytale and an epic celluloid abortion that reminds the viewer that the so-called ‘holocaust’ is not a historical event but a religion with its own belief system, with Uncle Adolf being the devil incarnate. That being said, forget Claude Lanzmann’s epic snooze-fest Shoah (1985), The Keep is a real and honest holocaust flick of DeMille-esque proportions.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

December 28, 2013

11

comments

![]()

Friday, December 27, 2013

Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve

From my personal experience as the proud grandson of a Flying Dutchman, the Dutch reign supreme when it comes to hyper negativity, cynicism, airs of superiority, and pathological Teutophobia. In other words, the Dutch people (aka ‘lazy Germans’) are proud assholes who derive a deluded sense of superiority from the fact that they are pathologically ‘liberal’ (i.e. decadent and lazy) and adamantly support degenerate and ethno-masochistic social causes. Indeed, Dutch auteur filmmaker Edwin Brienen (Terrorama, Revision - Apocalypse II) is certainly a dude who makes nihilistic and oftentimes nasty films, but what makes him different from the average Cheese-Eater is that he seems to have a rather nice relationship with the perennial enemy nation of Germany (aka the land of the boorish “Moffen”)—the Germanic brother country that occupied the Netherlands during the Second World War and stole all its cheese while the natives starved and froze to death—and has made a number culturally pessimistic Nietzschean melodramas there. Indeed, being described as the “Dutch Fassbinder” might be akin to being described as the “Dutch Hitler” for some Dutch people, but Brienen seems to wear the distinguished Teutonic title with pride. Recently, I was quite happy to receive a Christmas present from Brienen and his Berlin-based production company Ultra Vista in the form of the Dutch filmmaker’s (anti)Christmas cult movie Warum Ulli sich am Weihnachtsabend umbringen wollte (2005) aka Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve, which was recently fittingly re-released for the Holiday season. Sort of the Xmas film that Fassbinder never made, albeit more brazenly naughty and nihilistic, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve is certainly the ‘Satan’s Brew of Christmas movies.’ Made following the shooting of Brienen’s In a Year with 13 Moons-esque film Last Performance (2006), Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve was not only inspired by Fassbinder’s maniac melodramas but also by the Bavarian auteur filmmaker’s singularly prolific work ethic. Spurred by a whimsical idea Brienen had to complete an entire film (including shooting, editing, post-production, etc.) in a mere three to four works, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve was shot in less than two weeks and was already in Germany theaters two months after pre-production began. The only real Christmas movie that I watched on this past Christmas day, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve certainly got me in the “Bah! Humbug!” spirit as a tastelessly and even terrifyingly tragicomedic work about a pathetic loser who wants more than anything just for a single person to spend Christmas with him, but lacks the personality and social clique to attract even the most repugnant of Americanized Aryan degenerates, including his bitchy bull-dyke sister and obnoxiously extroverted transvestite father. Featuring clips from Frank Capra’s It's a Wonderful Life (1946) dubbed in German and elderly folks drinking themselves to death as they suffer yet another miserable and melancholy Yuletide, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve is probably the only Xmas film ever made that has the potential to both drive people towards and steer people away from the perennial gift of suicide.

Ulli (Marin Caktas) is an unremarkable fellow with a dead-end job as an exceedingly emasculated office slave who is rather determined to find someone special to spend Christmas with, but the problem is that he has about as much swag as an elderly old man’s wrinkled scrotum, not to mention the fact that he still worships his long gone ex-girlfriend Nicki (Eva Dorrepaal). In fact, despite being well into his mid-30s, Ulli has only had one girlfriend in his entire sad life and his dubious relationship with Nicki only lasted a mere 6 months, thus he has about as much experience with women as the average high school boy. Rather autistically, Ulli makes his first pathetic attempt at wooing a woman to spend Christmas with him by approaching his cute next door neighbor, who he does not actually know, with a would-be-thoughtful Xmas gift. Naturally, the girl blows him off like he is a creepy salesman and rejects his retarded gift, which is a vintage copy of J. D. Salinger’s absurdly overrated teen angst novel The Catcher in the Rye (1951). After his failed attempt at seducing his neighbor, Ulli goes to hang out with his British best friend Elton (Tomas Spencer). Rather annoyed by his feeble friend’s moody and broody bitch boy behavior, Elton verbally berates Ulli into oblivion, ultimately insulting him for his love of the rather repellant romantic-comedy Bridget Jones's Diary (2001) and eventually tells him to “fuck off outta here.” Despite kicking him out of his apartment, Elton later makes up with Ulli and the two bros-without-hoes naively attempt to buy hard drugs from a degenerate swarthy drug dealer named Heino (René Ifrah), who has a rather bizarre fetish for so-called ‘Latin music’ and big booty bitches like Shakira. Of course, when Heino’s slutty and slightly unhinged girlfriend physically dominates and attempts to molest Ulli, the two friends unfortunately leave drug-free.

Desperate for both love and affection, Ulli makes the moronic mistake of visiting his bull-dyke beastess sister Bettina (Nicole Ohliger) and her dude-like Dutch dyke girlfriend Karin (Esther Eva Verkaaik). Sister Bettina immediately attempts to throw Ulli out, but Karin makes him stay as she seems strangely turned-on by his company. After going on a painfully plodding and pretentious spiel about the purported homoeroticism of Leonardo da Vinci’s The Last Supper, Karin begins to get horny and starts feeling up the sexless office worker, which rather irks Bettina and results in a brutal battle between the two bull-dykes that concludes in rough lesbo sex. After getting in the Christmas spirit by eating an archaic-looking aluminum-bound TV dinner, Ulli goes to visit his man-mommy Evelyn (Ades Zabel) and her decidedly despicable Euro-wigger boyfriend Olaf (Niels Bormann). After Olaf—a fellow who is in a relationship with a less than homely transman—accuses Ulli of being a cocksucker, Evelyn reveals to her son that she has a tumor and will die of cancer in the next couple months, thus further compounding the offbeat office worker's undying depression and disillusionment with the holiday season. Feeling more desperate than ever, Ulli decides to take a strange stranger named Cat (Malah Helman) hostage with a toy prop gun, which initially proves to successful but the hapless hopeless romantic ultimately gets more than he bargained for. Indeed, Cat is a cute but somewhat creepy gal who attempts to get Ulli to strangle her as two awkwardly make misbegotten love in a bathtub, but the sensitive gentleman naturally refuses to do so, so the little lady leaves her kidnapper with the unflattering remark, “I really feel sorry for you” as if he is the most pathetic pussy in the world. After going to a church sermon and receiving nil solace after asking the stoic reverend why not a single one of the seven billion or so people that inhabitant the earth is willing to spend Christmas with him, Ulli contemplates suicide but naturally pussies out. In the end, Ulli spends Christmas in a retirement home inhabited by mostly senile and somber elderly folks and gets drunk with a resentful old fart that has no interest in speaking with him. Indeed, it is not a wonderful life after all, at least for postmodern untermensch Ulli.

Undoubtedly, in its malignant anti-merry melancholy, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve might have been better titled Why Didn’t Ulli Kill Himself on Christmas Eve? as the patently pathetic protagonist’s self-slaughter would have given him the gift-that-keeps-on-giving; eternal peace. In terms of pathetic male protagonists, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve ultimately puts the accursed cuckolds of Fassbinder’s Why Does Herr R. Run Amok? (1970), The Merchant of Four Seasons (1972), and The Stationmaster's Wife (1977) to abject shame. Of course, protagonist Ulli was not the only deplorable character featured in the film, as Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve does not feature a single likeable nor redeemable character. Indeed, featuring loony lesbian erotomaniacs, bastard ‘best friends,’ swarthy Shakira-saluting dope dealers, pompous charlatan preachers, erratic elderly old farts, sadistic Sapphic sisters, masochistic kidnap victims, and Euro-Trash wiggers, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve is certainly a insanely inconoclastic anti-It's a Wonderful Life of sorts where everyone is naughty and no one plays nice. A sleazily sardonic piece of celluloid coal in your much cherished vintage Christmas stocking, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve is the perfect cinematic Xmas feast for both anti-Santa-ists and subversive cinemaphiles alike. Indeed, I doubt auteur Edwin Brienen got any presents in is shoes from Sinterklaas this year after deciding to re-release Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve; arguably the most antagonistic yet hilarious anti-Christ-Mass ever made. A Christmas flick for those individuals who prefer Krampus over Santa Claus, Why Ulli Wanted to Kill Himself on Christmas Eve reminds the viewer that for every person that loves the holiday season, there are two or three other people who have hit rock bottom and cannot wait for the new year to begin and for the Christmas tree to be thrown in the dumpster.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

December 27, 2013

32

comments

![]()

Wednesday, December 25, 2013

The Child I Never Was

Great German serial killer films are certainly a dime of dozen. From German Expressionism with Fritz Lang’s M (1931) to German New Cinema with The Tenderness of Wolves (1973) aka Die Zärtlichkeit der Wölfe directed by Ulli Lommel and produced by Rainer Werner Fassbinder to the post-German New Cinema no-budget underground with Jörg Buttgereit’s Schramm (1994), it seems that krautland is king when it comes to fiercely fucked yet audaciously artful flicks about psychopathic killers of the insanely idiosyncratic sort. Of course, one of the reasons for such a prevalence of these films in Deutschland is due to the fact that Germany had a serial killer problem after the First World World (in fact, the childkiller of Lang’s M is a composite of a number of real-life killers, including Peter Kürten, Fritz Haarmann, Carl Großmann, etc.). Indeed, social and economic chaos made post-WWI Weimar Germany the perfect playground of perversity for both budding and refined serial killers alike. Of course the Second World War, which was even more deleterious than the First World War, also spawned a number of notable deranged psychopathic killers with an aberrant affinity for bloodlust, with kraut queer child killer Jürgen Bartsch—a foul fiend of a fellow who used to carry around the mutilated corpses of his child victims in plain public view via a suitcase (aka ‘children’s coffin’) of sorts and rather enjoyed fiddling with the naked and dismembered corpses of his kid victims in a secret cave hideout—being arguably the most creepily pathetic of these ice-cold killers. Born Karl-Heinz Sadrozinski in 1946 as the bastard son of a mother who died of tuberculosis shortly after his birth, Bartsch spent his first couple months being cared for by a group of nurses and was eventually adopted at eleven months of age by a butcher and his wife from Langenberg (today Velbert-Langenberg). With a wacked-out adoptive mother who suffered from OCD who would not little her little boy play with other children and who was forced to attend a sexually-repressive Catholic boarding school, bastard Bartsch was already a crazed cocksucker killer by 1961 at the mere age of 15 and would ultimately kill and dismember four boys between the ages 8 and 13 until he was caught and arrested in 1966 when his fifth would-be-victim managed to escape. As depicted in the German flick The Child I Never Was (2002) aka Ein Leben lang kurze Hosen tragen directed by Kai S. Pieck (Isola, Ricky: Three's a Crowd), the Bartsch case is notable due to the fact that it was the first trial in German jurisdiction history where psycho-social factors (i.e. the killer’s warped childhood) came into play when handing down the decidedly deranged defendant’s sentence. In the partially fictionalized biopic The Child I Never Was—a quasi-docudrama/melodrama hybrid utilizing the serial killer's own letters and essays (Bartsch spent some time while institutionalized documenting his tragic childhood, fears, passions, perversions, etc.)—Bartsch’s troubling teenage years, malevolent mutilation-based homoerotic murders, and post-trial confessions are depicted in strenuous and even sickening detail. In other words, The Child I Never Was is a terribly dark and uniquely ugly film about a terribly dark and uniquely ugly individual whose crappy childhood, overbearing pseudo-mother, and cock-blocking Catholic upbringing helped mold him into a pernicious poof pervert with a pathological case of Peter Pan syndrome.

For anyone to describe The Child I Never Was as an ‘enjoyable film’ would be nothing short of a puffery-plagued lie (or as sign of sexual sadism on the part of the viewer), though it is by no means a bad film, just a rather disheartening and thematically disgusting one. Aesthetically cold and sterile and thematically deadly serious and morbidly melancholy, The Child I Never Was is a film about a born bastard loser that was destined for infamy. Melodramatically depicting the life of Teutonic twink teen serial killer Jürgen Bartsch during his killer coming-of-age years, as well as his equally lonely prison years in the somewhat aesthetically sterile form of a docudrama-like tape confession, The Child I Never Was is the patently pathetic celluloid tale of a fucked fellow who would enter this world in a misbegotten manner and would leave in no less a ‘tragic’ fashion. As Jürgen Bartsch (Tobias Schenke) tells a camera at the beginning of the film, “During these six years in prison, things have been great with my parents. Maybe it’s because I’m a good boy now. The way I was at 9 or 10, maybe… I can’t imagine being apart from my parents. I also can’t imagine my parents dying. That’s a completely unbearable idea. I really like my parents. I’m happy when they come to visit me. Mind you, to be honest, 15 minutes is enough, you know?,” but as one learns while The Child I Never Was progresses, the demented boy's 'love' for his family is no more genuine than his halfhearted attempt at becoming a heterosexual via his failed teenage experiences with Essen-based female prostitutes at the age of 17 and post-arrest marriage to a naive nurse. The virtual slave of his exceedingly overbearing adoptive mother Getrud Bartsch (Ulrike Bliefert) for most of his short and sad life, Jürgen was not allowed to play with other kids as a child and if he got dirt on the rug, his pseudo-mommy would not think twice about calling him “a piece of shit” and slapping him around. As for Jürgen’s butcher adoptive father Gerhard (Walter Gontermann), the meathead of a man apparently never displayed a single inkling of emotion towards his adopted son until it was revealed that he was adopted. Of course, Jürgen’s biggest problem was that he was a closeted homo of the Catholic-reared sort and that he was so terribly desperate for little boy ass that he was literally willing to kill just to get it. With the peculiar boyish charm of a sort of kraut Leopold and Loeb, Jürgen would lure younger boys that looked quite similar to himself (i.e. dark/swarthy hair, small, scrawny, pedomorphic, etc.) with the promise of money/goodies, murder them inside his secret cave hideout, and fondle their dead corpses. After attempting to molest a friend who managed to getaway and tell his parents, Jürgen’s father Gerhard found out and quite naturally became concerned, even contacting social services about the incident, but apparently the ‘progressive’ West German government felt there was nothing to worry about. Of course, Jürgen eventually got bored with merely orally pleasuring the genitals of the dead boys, so he began cutting his victim’s body open and fiddling with their guts for maximum orgasmic excitement. Living with the subconscious desire to be caught for his actions as he confessed in his writings, Jürgen was eventually caught after making the mistaking of leaving a lit candle for his fifth and final would-be-victim, who managed to escape using the candle flame to burn off the rope that the pedo-killer bound him with. Apparently, Jürgen left the boy to watch television with his parents and planned to skin his victim alive when he got back, which certainly demonstrates the domesticated depravity of his mind and the schizophrenic double-life he led before he was caught.

While The Child I Never Was concludes pseudo-farcically on a strangely light note with Jürgen Bartsch doing a childish magic trick (or what he calls a “phenomenal trick”), the real-life sodomite serial killer disappeared from the world in 1976 in a strikingly fitting manner when he was only 29 years old. After marrying a nurse in a feeble and insincere attempt to ‘reintegrate himself into society,’ Bartsch opted for having voluntary castration (probably a procedure more pedophiles/serial killers should have!) in the hope he would not have to spend the rest of his life in a mental institution, but fate was not in his favor as he ultimately died on the operating table after an unskilled (and probably unsympathetic) nurse gave him an overdose of Halothane (inhalational general anesthetic). Undoubtedly, in its attempt to portray Jürgen Bartsch as patently pitiable being whose aberrant actions were not surprising considering his unhinged upbringing as an unwanted post-WWII bastard, The Child I Never Was is a total anti-titillating and emotionally terrorizing cinematic success as a sort of melodramatic kraut equivalent to the harrowing HBO documentary Paradise Lost: The Child Murders at Robin Hood Hills (1996). Additionally, the actor that played the young Bartsch, Sebastian Urzendowsky, was a perfect match in terms of appearance and essence. Like the real Bartsch (whose real birth surname was Sadrozinski), actor Urzendowsky is a pedomorphic fellow of the swarthy yet pale sort who, at least judging by his surname, is also a German of Polish ancestry. In that sense, The Child I Never Was also makes for a great piece of accidental anti-Polack propaganda as a work the features the most unflattering depiction of an ethnic Pole since the National Socialist propaganda flick Feuertaufe (1940) aka Baptism of Fire directed by Hans Bertram. Of course, in terms of Teutonic serial killer flicks, The Child I Never Was, not unlike Der Totmacher (1995) aka The Deathmaker directed by Romuald Karmakar, may be one of the better more recent works of the subgenre, but it is certainly not up to par with timeless works like Fritz Lang’s M, The Devil Strikes at Night (1957) aka Nachts, wenn der Teufel kam directed by Teutonic Israelite Robert Siodmak, and The Tenderness of Wolves. After failing to think of a Xmas-themed movie to view/review and remembering Kai S. Pieck’s serial killer flick had a deathly dreary Christmas dinner scene between Jürgen Bartsch and his maniac mommy, I decided that re-watching The Child I Never Was today would probably make for a ‘memorable’ tribute to J.C.'s birthday. Needless to say, The Child I Never Was managed to ruin any Christmas spirit I did have and if that’s not a good enough recommendation for a serial killer flick, I don’t know what is.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

December 25, 2013

0

comments

![]()

Sunday, December 22, 2013

Sombre

I am not a diehard serial killer fetishist or anything, but Sombre (1998)—an experimental work directed by French auteur Philippe Grandrieux (A New Life aka La vie nouvelle, Un Lac) about a violent serial killer/rapist of the perennially lonely sort who falls in love with a woman for the first time in his entire life—is easily one of the most darkly romantic and disturbingly beauteous films I have ever seen. Directed by an ex-video artist loosely associated with the so-called ‘New French Extremity’ movement, Sombre is a work of aesthetically majestic yet paradoxically minimalistic metaphysical horror depicting an innately impenetrable antihero living in a glacial zeitgeist who is provoked to rape and murder simply by being merely touched by a member of the fairer sex. Slaughtering sluts, prostitutes, and other wanton women along the frog countryside, the angst-ridden antihero of Sombre faces the most unsettling prospect of his entire life when a beauteous virgin falls in love with him and vice versa. A perturbing and penetrating love story for the foreboding age of Occidental decline, Sombre ultimately portrays the impossibility of love in our contemporary times where most Europeans think children are a nuance and marriage is looked at as a mere business transaction. The slightly saner yet more melancholy son of Gerald Kargl’s Angst (1983) and the more cultivated yet crazed celluloid big brother of Jörg Buttgereit’s nihilistic kraut serial flick Schramm (1994), Sombre is the cinematic cream of the crop when it comes to films about sexually dysfunctional and sadistic human predators. Directed by a filmmaker who has cited the films of F.W. Murnau, Robert Bresson, Stan Brakhage, and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, as well as the writings of philosophers ranging from Marcus Aurelius to Gilles Deleuze, as major influences, Sombre is a Weltschmerz-rattled and cognitive-dissidence-straddled neo-fairytale in the lunatic libertine spirit of Michael Stock’s Prince in Hell (1993) aka Prinz in Hölleland about a serial killer who acts as a puppet-master both on and off stage and who does whatever he wants, with whoever he wants, whenever he wants, so when his power is tested by the proposition of the uncontrollable—love, human warmth, and sexual ecstasy—he must come to terms with the little bit of ‘humanity’ he has left. A delectably deranging and discombobulating cinematic work that dares the viewer to dig deep in the decidedly dark abyss of a damaged mind that is attempting to persevere in the face of undying psychological sickness and plaguing pathology, Sombre ultimately seems like a serial killer flick that was directed by an actual (and rather quite sensitive) serial killer, as a sort of esoteric arthouse celluloid equivalent to Moors Murderer Ian Brady's book The Gates of Janus: Serial Killing and Its Analysis (2001).

Nordic frog Jean (Marc Barbé) is a man that certainly knows how to make children laugh and cheer wildly but he is also a curiously fucked fellow who knows how to make a woman scream for her life. Set in the French countryside during the Tour de France, Sombre follows the seemingly most somber man in rural frogland as he gives puppet shows to standing ovations of children, picks up prostitutes and ritualistically rapes and murders them with his bare hands, and eventually bumps into the seemingly most somber woman in rural frogland, thus offering him a rare chance at personal redemption. Jean has a very specific routine when it comes to raping and killing women that involves him making the unsuspecting victim strip bare while blindfolded and forcing them to spread their legs a couple inches from his face. Indeed, Jean stares at a woman’s naughty bits as if putting ‘pussy on a pedestal’, but at the same time he does not seem to know what to do with it, as if he is an impotent pedantic scientist taking a theoretical approach to sex. It seems that due to impotence and pent up sexual frustration, Jean can only derive of sense of solace and sexual release by strangling sluts to death. One day, gentleman Jean's view of life, love, and humanity is forever changed when he goes driving and offers to give a ride to a chick named Claire (Romanian Jewess Elina Löwensohn) whose car has just broken down. Unlike the lecherous ladies he typically picks up, Claire is a sensitive virgin who seems to suffer from a perennial form of sadness, as if she was once internally wounded and the scars failed to heal. Claire has a sister named Christine (Géraldine Voillat) who, on top of being a pseudo-blonde bimbo, is rather extroverted, especially in comparison to her somber sis. In between strangling to death prostitutes, Jean begins hanging out with both Claire and Christine. While Christine does everything she can to grab Jean’s warped gaze, including incessant skinny dipping, he only has eyes for Claire. One day whilst swimming at the lake, Jean decides enough is enough when it comes to Christine’s never-ending nakedness and starts strangling the loose lady and only stops just shy of killing her, which naturally perturbs Claire. After getting involved in a bizarre failed threesome in a seedy motel room that mainly involves Jean tying up the girls in bondage and smacking them around like slaves, Claire decides to help her sister escape by her putting on a train to paris, though she stays with the serial killer as she seems to believe she can save him from himself. As two terribly lonely and decidedly damaged individuals whose ‘faults’ seem to complement one another, Jean and Claire inevitably fall in love and somewhat attempt to become a real couple. In fact, Jean even makes passionate love to virgin Claire and thus he also loses his ‘vanilla sex’ virginity. Of course, Jean and Claire cannot last as a romantic entity as the former has a lust for brutality and the latter does not want to become a victim of the former’s lust for brutality. Since he truly loves her and is afraid of what he might do to her in the future, Jean rather reluctantly yet swiftly pushes Claire away by telling her to “get lost” and “vanish” after the two make passionate love, thus displaying love and mercy for another person for the first time in his loser life as god’s most lonely man.

A sort of tastefully sordid postmodern neo-fairytale (in one rather symbolic scene, Claire find and puts on a ‘Big Bad Wolf’ costume owned by Jean) told in a purely visual and mood-driven style reminiscent of the great poetic works of silent cinema (F.W. Murnau's masterpiece Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans (1927) certainly comes to mind), Sombre is easily one of the most strangely touching and singularly romantic films I have ever seen and unlike a film like Dahmler (2002) starring Jeremy Renner, Grandrieux actually manages to work in its unflinching ‘humanization’ of a sadistic serial killer. Indeed, in the end, antihero Jean of Sombre seems even more genuinely pathetic than Peter Lorre did in Fritz Lang’s M (1931). Additionally, Jean of Sombre does not seem like a cinematic caricature like Lorre in M, but more like a seemingly normal fellow who, if the viewer did not know any better, has something slightly off about him that one cannot quite pinpoint and that is what makes Grandrieux's work such a delectably disturbing piece of ‘humanistic horror.’ In the end, Sombre seems more like a romantic tragedy than anything else in its daunting depiction of two discernibly damaged soul-mates who might have been able to live a long life of mutual beauty with one another had it not been for each characters’ respective ‘hang-ups.’ A ‘thinking man’s serial killer flick’ that will surely bore the hell out of the sort of horror fanatic that gets an almost pornographic thrill from seeing the likes of slasher killers like Michael Myers and Leatherface in action, Sombre is a sort of Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer (1986) for those cinephiles who enjoy reading Schopenhauer over Fangoria. Such a viewer dividing work that it inspired those running the 1998 Locarno Film Festival to release the following official statement, “Half of the jury would like to call attention to Sombre. Our jury split between those who were morally offended by the film and those who saw a purpose in its darkness, and in the strength of its mise-en-scene and images,” Sombre is a true love story for a pre-apocalyptic age that has become disillusioned with love, and a zestless zeitgeist where men prefer porn and whores and where women prefer careers and cuckolds to actual true love and romance. Featuring an inconspicuously complimentary score by Alan Vega (frontman of the electronic protopunk duo Suicide), as well as a strange appearance by the classic Bauhaus song “Bela Lugosi's Dead,” Sombre is a fiercely foreboding work dripping with atmosphere that offers the filmgoer more than just a mere film, but an oneiric celluloid odyssey that totally transcends most people’s comfort zones. Auteur Philippe Grandrieux’s first ‘official’ feature film (though he has been making video art and instillations since the 1980s), Sombre may be a majorly melancholy work that pricks and prods at the soul without mercy, but it is also ample evidence that film as an artistic medium is far from dead and that some cinematic territories have only been marginally explored. Indeed, if you thought David Fincher made the serial killer film a respectable subgenre with big budget and superficially stylized melodramatic swill like Se7en (1995) and Zodiac (2007), you have yet to be metaphysically touched by a cinematic manhunter in the way that only Grandrieux’s Sombre does.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

December 22, 2013

11

comments

![]()

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.