Tuesday, November 12, 2013

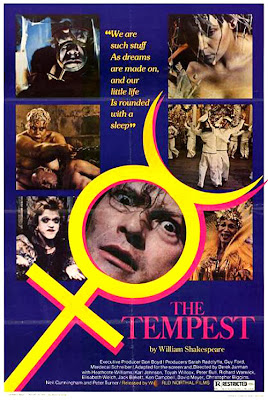

The Tempest (1979)

Admittedly, I am not much of a Shakespeare connoisseur, largely because I never bothered to read much of his work in high school or elsewhere, so I certainly have no problem with the fact that British auteur Derek Jarman butchered the all-too-famous English playwright’s work with his punk high-camp flick The Tempest (1979). Indeed, while Peter Greenaway’s Prospero's Books (1991) featuring John Gielgud (who was ironically originally set to star in Jarman’s flick) might be the most idiosyncratic and experimental take on Shakespeare’s play The Tempest (1610–11), Jarman's screen adaption is surely the most aesthetically pleasing, decidedly decadent, and fittingly updated take on the bard's final play. Incidentally, Jarman’s The Tempest also happens to be the first feature-length screen adaption of the Shakespeare play, though Broadway theatre director George Schaefer directed a TV version of the work in 1960 for the television anthology series Hallmark Hall of Fame. Although receiving a number of positive reviews from Shakespearean scholars upon its release, Jarman’s The Tempest was despised by a number of prissy Shakespeare purists and was even described in The New York Times by star critic Vincent Canby as being, “funny if it weren't very nearly unbearable. It's a fingernail scratched along a blackboard, sand in spinach, a 33-r.p.m. recording of ''Don Giovanni'' played at 78 r.p.m. Watching it is like driving a car whose windshield has shattered but not broken. You can barely see through the production to Shakespeare, so you must rely on memory,” thus ultimately ruining its chance of receiving popularity in the United States, or so described by Jarman biographer Tony Peake. And, indeed, featuring virginal 14-year-old Miranda being portrayed as a slutty and less than youthful punkette with kinky negro-esque hair by degenerate punk diva Toyah Willcox, a rather youthful yet radically resentful and even sinister Propsero portrayed by Heathcote Williams who gets off to exploiting his servants, real Jungian/Cabbala-inspired magic, a grown Caliban as portrayed by blind gypsy mime Jack Birkett (aka 'The Incredible Orlando') suckling on his discernibly grotesque and obese man-like mother Sycorax’s breast, super gay dancing Querelle-esque sailors, and high yellow American diva Elisabeth Welch giving a conspicuously campy cabaret-inspired performance singing Cole Porter’s “Stormy Weather” in what would ultimately be the singer/actress’s final film role, Jarman's The Tempest is Shakespeare as delightfully dreamed up by post-WWII England’s foremost arthouse auteur and postmodern Renaissance man. A decidedly debased depiction of Shakespeare’s play as adapted by a celluloid alchemist whose cinematic oeuvre is riddled themes regarding the drastic decline of English culture and The British Empire, Jarman’s The Tempest is a fiercely phantasmagorical and even Gothic work that delicately deconstructs and reconstructs the original play in a mystifying manner that still manages to pay respectful homage to its source writer.

Living in exile in a shadowy mansion (the film was shot on location at the Stoneleigh Abbey) on a desolate island with his sexually repressed daughter Miranda (Toyah Willcox) after being banished there by his treacherous brother Antonio (Richard Warwick) and the King of Naples Alonso (Peter Bull), the Right Duke of Milan Prospero (Heathcote Williams) conjures a tempest with his slave spirit Ariel (Karl Johnson) that will reunite all of these people in the same home. Creating a storm that wrecks an Italian ship carrying Antonio, Alonso and his son Ferdinand (David Meyer), as well as the King’s drunken mariner Stephano (Christopher Biggins) and his friend Trinculo (Peter Turner), on to his island, Prospero is waging a conspiracy against enemies that ultimately sires a number of conspiracies against him. When King Alonso’s son Ferdinand reaches the island, he instantly becomes a firewood-chopping slave of Prospero, but the malicious magician’s daughter Miranda soon falls in love with the enemy’s spawn and vice versa in a quasi-Romero and Juliet-esque fashion. Meanwhile, Prospero’s debauched and fish-like slave Caliban (Jake Birkett), whose attempted rape of Miranda is not depicted in Jarman’s The Tempest (though one sees Caliban harass the little lady while she is washing her bare bosoms), runs into drunkards Stephano and Trinculo on the beach and enthusiastically joins up in a conspiracy to murder the magician. Although a magician of sorts by trade, Prospero wants reasons to conquer all in the end, but his daughter Miranda simply wants a boy toy in the end. Not unlike savage slave Caliban, sassy supernatural spirit Ariel also wants his freedom, hence his involvement in conjuring the storm that wrecked the Italian ship carrying King Alonso and his eccentric entourage. While Prospero is the great magician, it is ultimately his seemingly dunce-like debutante daughter Miranda who casts the most powerful spell in her love-at-first-sight romance with Ferdinand. In a scenario inspired by an real-life incident involving Jean Cocteau bringing 21 sailors to his friend’s 21 birthday, Jarman’s The Tempest concludes with a literal golden wedding between Miranda and Ferdinand involving dancing sailors and Elisabeth Welch as a ‘golden goddess’ (or more liked colored camp diva) symbolically singing “Stormy Weather” in a bittersweet conclusion director Derek Jarman described as follows to the International Herald Tribune, “I don’t want to bless the union as Shakespeare did…because the world doesn’t see the heterosexual union any more as a solution. Miranda and Ferdinand may go into stormy weather.” Indeed, Jarman's The Tempest is not exactly the most ‘straight’ Shakespeare adaption.

As Tony Peake explained in his book Derek Jarman: A Biography (2000), “Although Jarman maintained that what had always interested him about The Tempest was that ‘no one can pinpoint the meaning’, his own reading of the play was fairly unequivocal and deeply pessimistic. Jarman’s Prospero is, in the words of Michael O’Pray, ‘sinister, intense, secretive and cruel’.” Indeed, Jarman’s The Tempest is a film about a lonely and exiled man who will stop at nothing to destroy the lives of his enemies, ultimately leaving the ‘anti-hero’ more lonely and emotionally defeated in the end, with his daughter becoming a member of his arch nemesis' family. Set in a metaphysically haunted “house of dreams” and “island of the mind” with cabbalistic symbols chalked on the walls and melancholy spirits riding Victorian toy horses, the Prospero of Jarman’s The Tempest is not the alter-ego of Shakespeare as typically presumed, but what seems to be a composite of Jarman himself and his hero John Dee, the Renaissance magician who, not unlike the director himself, fell prey to the hostility of lesser minds, especially those with an aversion to artsy fartsyness. While surely not Jarman’s greatest, most ambitious, nor most personal work, The Tempest is undoubtedly one of his, if not his most, accessible work as a curiously ‘queer’ take on Shakespeare that somewhat successfully does the seemingly impossible by bringing new lifeblood and true magic to the somewhat played out play. With his subsequent cinematic effort The Angelic Conversation (1985)—a highly experimental and mystically homoerotic work the director regarded as his best film—Jarman juxtaposed dreamlike slow-motion images of dandy twinks with off-screen narration of 14 Shakespeare sonnets read by Shakespearean actress Judi Dench. A sort of celluloid moving painting drenched in alchemy and esoteric ecstasy, The Angelic Conversation is certainly Jarman at his most cine-magical, but also rather indicative of why the filmmaker chose to depict Shakespeare the way he did in The Tempest as a man who believed in magic, at least in the aesthetic and cinematic sense as demonstrated by his remark,“film is the wedding of light and matter – an alchemical conjunction.” Dedicated to the memory of Jarman's mother Elizabeth Evelyn Jarman, The Tempest is a tastefully trying tribute to old school English kultur directed by a man who mourned the past but was surely himself a product of his decadent zeitgeist, hence why the film still seems rather fresh and innovative today, yet also so unequivocally British. Indeed, in its depiction of Prospero as a fallen hero from a fallen family who is blinded by hate and who has lost sight of what is important, Miranda as a loose floozy who screws the first young man she bumps into, and Caliban as a swarthy untermensch who pays back his teacher/caregiver by attempting to defile Prospero’s daughter, Jarman’s The Tempest features a maniac microcosm depicting the cultural and spiritual malignancy that consumes the Occident, especially post-colonial England, today. Just as Derek Jarman himself would do while slumped over his desk at his cottage in The Garden (1990), The Tempest concludes with Prospero laying lifeless with defeat. Just as his hero Pier Paolo Paslini died with his Trilogy of life, Derek Jarman brought high-camp and crude comedy to the classics, which is both an aesthetically noble and nefarious act for which he should be respected.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

November 12, 2013

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.

No comments:

Post a Comment