Wednesday, August 28, 2013

Chinese Roulette

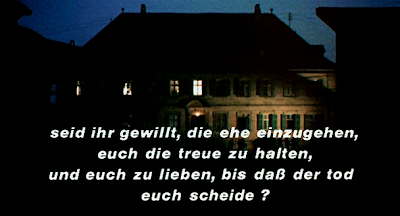

German New Cinema master auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder (The Marriage of Maria Braun, Querelle) died before he ever got the opportunity to direct a film in Hollywood, which at various points during his career he admitted he wanted to do, yet he did a direct couple films that seemed contrived and slick enough to have been assembled in Tinseltown, including Despair (1978) and Lili Marleen (1981), but indubitably the ill-fated filmmaker’s tragicomedic gothic psychological thriller Chinese Roulette (1976) aka Chinesisches Roulette radiates this manufactured studio essence the most, as if Alfred Hitchcock was forty years younger and had stopped in Germany to direct an international work with an all-star European cast. And, indeed, considering it was Fassbinder’s first international co-production and most expensive film up until that point (at an estimated DEM 1,100,000), Chinese Roulette was indisputable proof that the director, unlike many German filmmakers of his generation, was more than willing to make cinematic works that were not just accessible to Germans and other Europeans, pretentious cinephiles, and idealistic left-wingers. Admittedly, when I first saw Chinese Roulette—a work with a seemingly marketed running time under 90 minutes, cutting edge music by German electronic group Kraftwerk, and a tightly scripted and conspicuously contrived storyline—I felt it was not much more than a neatly assembled celluloid novelty directed by an arthouse filmmaker who wanted to try his lot at creating a somewhat mainstream thriller that would give him a larger audience and my opinion has not changed much since subsequent viewings, even if the work has grown on me since then and I believe that despite the film's formulaic thriller structure, it is probably far too nihilistic and misanthropic for the everyday filmgoer to appreciate. Shot in a small castle owned by cinematographer Michael Ballhaus (The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant, Goodfellas) located in Stockach in Unterfranken, Germany and co-produced by Michael Fengler (who previously co-directed Why Does Herr R. Run Amok? (1970) with Fassbinder) and Franco-Swiss auteur Barbet Schroeder (General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait, Maîtresse) and starring French arthouse divas, including Jean-Luc Godard’s muse Anna Karina and Macha Méril (Godard’s A Married Woman (1964) aka Une femme mariée, Buñuel’s Belle de jour (1967)), Chinese Roulette is a sort of anti-bourgeois thriller clearly made with the bourgeois in mind as a sort of acidic aesthetic attack on the upper-middle class by taking them to task on their lives of lies and luxury, especially where it hurts most; the traditional institutions of family and marriage. Centering around a seemingly unloved yet spoiled crippled little girl who essentially unleashes an elaborate game of emotional terrorism against her philandering parents, Chinese Roulette shows what happens when a wife and husband and their extramarital lovers are unwittingly forced to stay together under one roof while their sole child plays ‘mind games’ with them that eventually erupts into attempted murder during a psychodramatic game of Chinese Roulette which more resembles Russian Roulette in the end.

Ariane (Margit Carstensen) and Gerhard Christ (Alexander Allerson) are a wealthy Munich couple that plan to spend their weekends on opposite ends of Europe, as the wife claims to be going to Milan, Italy while the husband plans to stay in Oslo, Norway. Of course, both Ariane and Gerhard are lying and having extramarital affairs, so things get a little strange when they both make the unwitting mistake of taking their secret lovers to their shared country home, Traunitz castle. The Christs have a 12-year-old crippled daughter named Angela (played Andrea Schober, who also starred in Fassbinder's The Merchant of the Four Seasons (1972) as a little girl who had the misfortune of witnessing her mother's infidelities) who, despite still playing with dolls, is a rather clever and even cold and callous girl who especially hates her mother Ariane, who seems to hate her deluded daughter even more. When Gerhard and his French hairdresser mistress Irene Cartis (Anna Karina) run into Ariane and her boyfriend Kolbe (Ulli Lommel), who works for her husband, at Traunitz castle by what seems to initially be happenstance, they handle the situation rather well and decide to carry on the weekend getaway as a fucked foursome. The castle is run by a bitchy housekeeper named Kast (Brigitte Mira) who absurdly describes people that cut her off while driving as “fascists” and her sexually-confused, dildo-hiding dilettante writer son Gabriel (Volker Spengler). Although a virtual slave whose life essentially consists of groveling like a dog for her servants, Kast has nothing but sheer and utter contempt for the Christ family and her opportunistic son Gabriel hopes to exploit Gerhard’s work connection so he can get a writing deal. Later it is revealed that the Christ’s daughter Angela designed the elaborate plan to get her parents and their lovers all under the same roof and literally caught with their pants down (Gabriel initially walks in on his wife Ariane and his employee/her lover Kolbe on the floor in embrace) while engaged in mutual infidelities. Of course, things do not really get bad until Angela makes an unsuspected arrival to Traunitz castle with her mute nanny (Macha Méril), whose name is also Traunitz.

After rhetorically asking Gabriel “Would you want to sleep with a cripple?”, Angela also confesses to the servant boy, “Do you know how long Daddy has been cheating on Mother with that woman?...Eleven years. And do you know what happened 11 years ago? I fell ill 11 years ago. It’s as simple as that. Everything is simple. Life itself is simple. I learned that from Traunitz,” thus revealing that she believes she is responsible for the dissolution of her parent’s marriage and the reason she believes her mother hates her, further adding, “In their hearts, they blame me for their messed-up lives.” And, indeed, Angela seems to be right because while outside, her mother Ariane picks up a gun and locks her daughter's head in the crosshairs from an upstairs window, which naturally disturbs Gerhard, Kolbe, and Irene, the latter of whom pull the gun away from the little girl target. Naturally, Angela makes various attempts to play her parents and their lovers against one another, but terroristic tension does not reach its boiling point until the cruel cripple convinces everyone at the Traunitz castle to play a game of ‘Chinese Roulette’, a devilishly psychology-driven and self-incriminating game were players divide into two teams, where one group tries to guess what each individual member the other group is thinking of by asking questions like, “In the Third Reich, what would the person have been?,” which is inevitably the last question asked during the game. Angela ultimately decides the members of each team, with her mother Ariane, Kast, Kolbe, and Irene on the first team (which is clearly comprised of the people she hates most) and herself, her father Gehard, Traunitz, and Gabriel on the other team. Of course, Angela’s team has picked her own mother as the member of the other team who her group is describing. In terms of what writers might have invented the person, Gerhard picks Goethe, Gabriel picks Nietzsche, Angela picks Oscar Wilde, and Traunitz picks the best of all with Satanic National Socialist horror writer Hanns Heinz Ewers. When asked “What would this person be in the Third Reich?,” Angela’s answer is a “Commandant of the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen.” When Ariane finally realizes her daughter has compared her to a Jew-gassing death camp commandant, she flips out, tells her she is “a horror. A dirty, revolting little beast,” picks up a pistol, and shoots Traunitz (who she knows is her daughter’s only friend and, as the film hints, possibly her lesbian lover). It is subsequently revealed Traunitz is ok and that she received nothing more than a superficial flesh wound. During the postgame wrap, Gabriel states to Angela, “You knew something like this would happen, didn’t you?...But you wanted her to shoot you.” Clearly irked, Angela responds to Gabriel by telling him that she has known for two years that he is a hack writer who has plagiarized everything he has ever written. In the last scene before the credits roll, a second shot is heard outside the house, but the shooter and victim are left up to the viewer’s imagination in what is Fassbinder’s psychological attack against the viewer. Undoubtedly, in Chinese Roulette, no one wins and everyone loses; it is just a matter of how much each individual loses, especially in regard to their civility and sanity.

While undoubtedly one of auteur Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s least personal and least autobiographical works, Chinese Roulette reveals a good deal about the director’s sometimes sinister, sadomasochistic, and Svengali trickster character. In fact, Fassbinder was known to play Chinese Roulette with his friend and asked/answered questions no less provocative and malicious than those of the characters in his film. It should be noted that Chinese Roulette was the last film Fassbinder collaborated with Ulli Lommel on before the actor completely changed trades and permanently moved to the United States where directed two films for Andy Warhol before starting his dwindling career as a maker of direct-to-DVD z-grade horror flicks. Lommel was apparently dating Anna Karina at the time and managed to get her to star in Chinese Roulette, thus depicting the actor-turned-director at his ‘romantic playboy’ prime, before he became the butt of jokes to impotent fanboys and gorehounds who have never actually seen his films. Despite its modern soundtrack (Kraftwerk’s “Radioactivity” was a new single when the film was released), beauteous sets, mathematical camera angles, and contrived and precisely constructed storyline, Chinese Roulette is a brazenly brutal work of unrelenting doom and gloom and was ultimately hated by West German audiences upon it its initial release, which is no surprise considering it is a blatantly bourgeois work that shows no mercy in malevolently assaulting the psyche of the bourgeois viewer.

As a man born into a cultivated but unloving Bavarian bourgeois family whose father essentially wanted nothing to do with him and whose mother had more interest in her young boyfriend than her son, Fassbinder certainly seems to side with the character of Angela in Chinese Roulette, whose hopeless undying desire for love and affection propels her into baiting her mother into trying to kill her so as to put her out of her own misery. Undoubtedly, virtually every character in Chinese Roulette is dead inside and learns nothing from their nearly-deadly game of Chinese Roulette, thus demonstrating Fassbinder's disillusionment with not only the nuclear family and bourgeois values, but post-cultural consumer-based Occidental society in general, which has only degenerated all the more since the film’s release. Fitting somewhere in the writings of Harold Pinter and the films Mommie Dearest (1981) and Ingmar Bergman’s Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), Chinese Roulette is a sort of more hot than hokey hagsploitation flick where the hag is a miserable MILF and connoisseur of Haute couture, thus making the film an all the more bittersweet tortuous celluloid treat to swallow. Seamlessly mixing high-camp with high-class, Fassbinder demonstrates his destructive disdain for all facets of bourgeois life with Chinese Roulette, a film about an unhinged unmother whose disdain for her sole child Angela Christ ultimately results in the second spawning of a 13-year-old antichrist who, being a seemingly suicidal cripple who is unlikely to reproduce, acts as the final genetic line of the family, just like the director himself (who was himself a sole child and a homosexual who never reproduced). Arguably the greatest director of nihilistically naked and hysterical cinematic melodramas who has ever lived, as well as a perniciously possessive poof whose actions led to the death of 2 of his 3 great loves (one of them, Armin Meier, who later committed suicide, appears in an uncredited role in Chinese Roulette as a gas station attendant), Fassbinder more than likely possessed the inner-child of a little attention-deprived girl and with Chinese Roulette he undoubtedly traps the viewer into his world of menacing mind games, but, I for one, must admit I enjoyed playing and will pray that I never have a pissed cripple for a daughter. While Chinese Roulette is easily one of Fassbinder's most fundamentally formulaic and concisely constructed works that certainly proved he could do more with less in terms of assembling a thriller than the average Hollywood for-hire hack director, the film also demonstrates that he was an absurdly audience-antagonistic man whose works would have easily offended the morals of the American filmgoer, thus it is probably for the better that he never made it to the corporate Hollywood studio system, even if he would have indubitably done damage worth noticing.

-Ty E

By

soil

at

August 28, 2013

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.

Why didn`t you show any images of the daughters face ?.

ReplyDelete