-mAQ

Tuesday, April 12, 2011

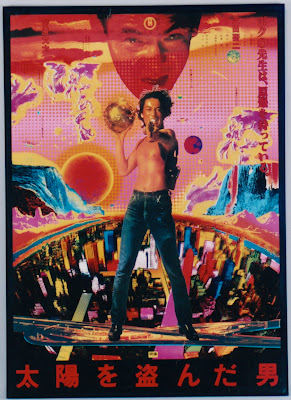

The Man Who Stole the Sun

Earlier on in the year I reviewed a film entitled The Youth Killer, a Japanese coming-of-age film that could be accurately labeled a "snoozefest". Past the infantile antithesis, The Youth Killer is remembered as one of two films from Kazuhiko Hasegawa, a director who disappeared from the scene as early as he arrived. It is as if Hasegawa picked up a camera for a short period of time just to perform a ritual similar to the act of trepanning - alleviating pressure allowing for a permanent "high". Hasegawa's other film, which garnered skepticism upon finishing The Youth Killer, is an award-winning Japanese satire called The Man Who Stole the Sun. Going in with the promise of excellence, The Man Who Stole the Sun not only kept me enthralled but actually managed to inspire, impress, and polarize me on the battlefield of criticism towards his few works. Was I being unfair in my review of The Youth Killer? This is a question that I asked myself after watching The Man Who Stole the Sun. Nevertheless, only time and an additional viewing can cement my position on the lower-half of Hasegawa's "career".

Born in Hiroshima on the January of 1946, Hasegawa managed to be given life under the most dynamic of post-war scenarios - directly following the detonation of "Little Boy". These dire straits of which he was sheltered through no doubt influenced his greater good and lent much to the creation of The Man Who Stole the Sun. The plot follows a renegade science teacher who short-circuits under the pressure of a hostage situation and the tedious nature of Japanese youth and decides to create a personal atomic bomb. These are assumptions without much physical evidence, though. In all honesty, I'm really unsure of the definite reason behind our lead character, Makoto Kido's, lapse in violence. Surviving the hostage situation with the help of a police inspector named Yamashita, Kido makes ample usage of his new lease on life and burgles a power plant for a large amount of plutonium (of which is shot in a manner that reflects the groovy nature of Danger: Diabolik). Shown in incredible detail, Kido then creates his atomic bomb and then proceeds to hold Tokyo hostage. Unsure of what he wants, Kido assumes the identity of "Nine" and goads a bubble-headed disc jockey named "Zero" into helping him decide his demands - which includes bringing The Rolling Stones to Tokyo.

Sadly, The Man Who Stole the Sun has fallen into the long list of films that precede discussion with "...the Japanese answer to Taxi Driver", which couldn't be farther from the truth. Other than wielding a handgun and displaying general misanthropy, Makoto Kido isn't the Japanese Travis Bickle and never will be. One might be able to substitute the role of Jodie Foster's for the atomic bomb as both are similarly idolized as a token of peace and a guiding light for both reign of terrors. In fact, the relationship between Makoto Kido and his nuclear weapon borders obsession. He sleeps at night cradling the plutonium in its raw compound and even spoons with the finished armament. As the plot progresses the hinting of plutonium poisoning is dropped like an anchor when Zero pulls out a clump of Kido's hair. Even when Kido finds out, he refuses to leave the beauty alone, lest he becomes as powerless as he was prior. Hasegawa spits in the face of the preconceived notion of refusing false idols with this visual memorandum of his. The atomic bomb is the center of our story and is given much more depth into its creation and purpose than Kido's driving force for terror. Another incredible aspect of Kido's character is the two-toned behavior patterns he exhibits. During chase scenes and the many confrontations that await him with Inspector Yamashita, Kido demonstrates a remove of a villainous archetype. Yet, when with Zero and his weapon, he battles his demons either by seducing Zero then tossing her into a river or displaying bouts of happiness mixed with melancholy. Makoto Kido is surely a conflicted character of interest.

The Man Who Stole the Sun is nowhere near a perfect film; essentially, it baths in pop culture, giving the events a certain familiar weight, but unfortunately over-complicating elements of the plot. Hasegawa has certainly created his masterpiece - an often humorous, often thrilling, and often frightening experience in pulp cinema. Armed with the finest elements in post-war terror, action, and occasional caper material, The Man Who Stole the Sun is an entry in personal filmmaking that is widely accessible to all. Its blend of biting satire with allusions to genocide are rather sobering in contrast with the nonstop hi-jinx of the film. For instance, the scene in which Kido fantasizes about dumping the shreds of spare plutonium in the pool, killing women and children, is a punch to the gut that disagrees with the tonally challenged happenings of the first hour (did this really take place?). Most importantly, Hasegawa is, himself, a part of the history behind an atomic bomb which makes this superior project fitting in a historically important sense. Tyrannical spirits the world over can find something to love in the better half of Hasegawa's body of work. When it comes down to it, The Man Who Stole the Sun actually gives me better memories and insight of his previous film The Youth Killer. This is what it is - total, senseless anarchy and a kaleidoscopic mishmash of Japanese culture served fondly with an ending that will leave you staring blankly at your television set. How did it get to this point?

-mAQ

By

soil

at

April 12, 2011

![]()

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Soiled Sinema 2007 - 2013. All rights reserved. Best viewed in Firefox and Chrome.

No comments:

Post a Comment